China’s decision to impose an Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) over a large part of the East China Sea has heightened tensions in an already volatile area, and appears to have dashed Japanese hope for a thaw in relations. The brouhaha that accompanied the announcement of the ADIZ was not so much about China’s legitimate right to set up such a zone as it was about the unilateral and bullish way it was imposed.

The ADIZ is the latest in a series of Chinese actions that combined seem to show a contradiction in the way the Asian giant engages its neighbors. This contradiction undermines Beijing’s diplomatic outreach to its immediate neighbors. Take ASEAN, where China appeared to have largely succeeded in building an image of a peaceful partner in a region torn between the fear of an assertive giant up North and the temptation of doing business with the world’s second economy, at a time of growing uncertainty about U.S. reliability in this part of the world. China was even able to form an economic partnership with Vietnam, a historical foe and long-time adversary in a territorial spat over the Spratly Islands.

This is where the contradiction begins. While in recent months Chinese President Xi Jinping and Premier Li Keqiang have mounted a charm offensive in Southeast Asia, the painstakingly built image of Chinese goodwill in Southeast Asia literally evaporated overnight following the inelegant Chinese response to Typhoon Haiyan in Philippines. It did not help neither when, after hurriedly dispatching a People’s Liberation Army Navy hospital ship in response to worldwide criticism, China also chose to dispatch its new aircraft carrier, the Liaoning, to the South China Sea, scene of multiple maritime disputes with Southeast Asian countries.

ASEAN leaders visited Tokyo for a December 13 summit commemorating the 40th anniversary of Japan-ASEAN friendship. The Chinese ADIZ could not have come at a better time for the 10 ASEAN leaders to assess the Chinese threat, as they flew by – if not through – the new zone on their way to Tokyo.

A Honeymoon Ended

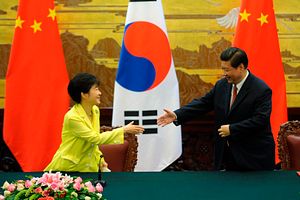

An unexpected victim of China’s ADIZ is its newly acquired friendship with South Korea. United by their shared resentment of Japan’s nationalist leader Shinzo Abe, these two neighbors embarked five months ago on a rapid political and economic rapprochement. The Sino-South Korean “honeymoon,” unthinkable during the Cold War, has left Japan in total isolation in its neighborhood and constitutes a headache for the U.S., which has no interest in seeing the rift widen between its two most important allies in Northeast Asia.

In June, South Korean President Park Geun-hye even broke with long-held diplomatic tradition by making a landmark visit to China before visiting Japan.

However, subsequent developments, such as China’s slowing economic growth, a lingering territorial feud, mutual mistrust on mainly security issues, and China’s apparent failure to keep a check on North Korea, have since contributed to cooling the ardor, prompting South Koreans to begin to have second thoughts about their new friendship.

The recklessness with which China established its ADIZ, which not only overlaps South Korea’s own but also covers the Ieodo islet in the Yellow Sea, which is claimed by South Korea as its territory, infuriated the South Koreans. This has in turn allowed some in Japan to hope that a shared security concern might yet end up driving the South Koreans back to their more traditional friends in Japan.

A Détente Stymied

China’s ties with Japan have, of course, been rocky for some time. But a closer look reveals that Beijing has in recent months offered multiple discreet signals that it might be willing to explore the possibility of a thaw. Those signals include the high-level reception accorded in Beijing to a delegation of 100 Japanese top business leaders, a forum in Beijing of influential personalities (such as journalists and former senior high officials) from both countries in an attempt to break the ice, meetings of retired military officials from the two countries eager to find ways to avoid a disastrous armed conflict, press reports of a secret visit to Tokyo by a high-ranking Chinese official, instructions given to journalists not to overplay anti-Japanese sentiment in their articles, and a quiet clampdown on the production of popular but excessively anti-Japanese TV dramas.

Japan also reciprocated. Despite his nationalistic tendencies, Abe has refrained from visiting the controversial Yasukuni Shrine, where war criminals are worshipped alongside other war victims. He also went out of his way to honor a Chinese student who rescued a drowning child in Japan. And a delegation of Chinese business leaders was also given VIP treatment when they visited Japan last month.

As in the case of ASEAN, all this fragile and delicate buildup of goodwill towards a possible Sino-Japanese détente literally collapsed overnight with the announcement of the ADIZ.

The fact that the new zone covers the disputed Senkaku/Diaoyu islands has only added to the sense of crisis and Sinophobia already bubbling in Japan. Some observers suggest that China has in fact done Abe a favor. For months, the Japanese leader has been trying to convince a reluctant nation to give him almost a blank check (such as a controversial state secrecy bill) to drastically beef up both internal security control (a nightmare for democracy advocates) and Japan’s military capabilities. Thanks to Beijing, Abe now has a much more acquiescent parliament.

The Roots of Contradiction

This contradiction in China’s foreign policy can be blamed on multiple factors, including a need to divert attention away from social instability at home and political rivalry among different leadership factions, especially after the recent Third Plenum. It can also be explained by the particular role of the People’s Liberation Army in China.

For instance, the ADIZ may not necessarily reflect the will of China’s top leadership. As a recent Wall Street Journal article rightly noted, the strange lack of enthusiasm in the way Chinese official press deals with the Chinese ADIZ issue seems to support the view that the top leadership in Beijing did not necessarily want this.

As in other countries, the Chinese leadership is not immune to factional divisions and power grabs. When it comes to foreign policy, there is a constant seesaw game between those striving for a “peaceful rise” and those advocating for more assertive behavior to remind the world that China is no longer the Sleeping Giant.

The particular status of the PLA as an “Army of the Party” (not of the State) guarantees it a special influence in the way the Party and the nation are run. In this respect, taming the PLA has always been a sensitive political priority of the highest degree for any leader in Communist China.

The Third Plenum in November produced a string of landmark reforms. Perhaps the most notable calls for the creation of a State Security Committee (SSC) to coordinate and oversee foreign and security policies.

It is understandable that different factions within the Party and the government, including those in the PLA, are engaged in a fierce fight to secure advantageous positions within this powerful new apparatus. The sudden announcement of the Chinese ADIZ may have been a byproduct of this fight for influence, in the sense that hawkish elements within the PLA may have wanted to put on a show of force both for internal political appeal and for international standing.

In another, less remarked aspect, there is also an economic side to the behavior of the PLA. Namely, some officials may, without actually going to war, want to maintain a heightened state of tension with Japan and America.

In his 1961 farewell address to the nation, U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower famously warned of the powerful military-industrial complex in America. Subsequent American history has only underlined his prescience.

In today’s China too, there is a powerful military-industrial complex comprising mainly State-run enterprises. The People’s Liberation Army itself is to some extent a huge business and industrial complex with vested interests in military and other domains. As in America, these vested interests tend to do well when there is heightened international tension.

Masahiro Yumino, a Chinese affairs expert at Tokyo’s Waseda University, noted in Wedge magazine last week that shares in many defense conglomerates in China have spiked since the announcement of the Chinese ADIZ.

Yo-Jung Chen is a retired French diplomat. Born in Taiwan and educated in Japan, he has served in Japan, the U.S.A., Singapore and China.