Over the last month and a half, seven significant developments indicate that tensions in the South China Sea are set to rise in both the short and long term. The five short-term trends include: Philippine defiance of China’s fishing ban; continued inaction by the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN); the Chinese navy’s repeated assertions of sovereignty over James Shoal; the possibility of an Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) over the South China Sea; and stronger United States opposition to China’s ADIZ and maritime territorial claims.

First, in January, the Philippines stepped up its public defiance of China and its territorial claims in the South China Sea. On January 15, Emmanuel Bautista, Chief of Staff of the Armed Forces of the Philippines, stated in a television interview with respect to new fishing regulations issued by Hainan province that Filipino fisherman should not give in to threats or intimidation. A day later, Secretary of Defense Voltaire Gazmin stated that the Philippines would disregard Hainan province’s new fishing regulations and would provide escorts to Filipino fishermen in the West Philippines Sea “if necessary.”

On January 17, the local media published aerial reconnaissance photographs taken at Ayungin Shoal (Second Thomas Reef) on August 28, 2013. The photographs showed the presence of two People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) warships, including a frigate, and a Coast Guard vessel. The press quoted from a confidential government report that stated the Chinese naval presence “could be part [of] a renewed and possibly more determined effort to remove Philippine military presence on Ayungin Shoal and from the whole Spratly island group.”

On February 4, President Benigno Aquino in an interview with The New York Times called on the international community to lend its support to resist China’s claims in the South China Sea.

Second, the ASEAN Foreign Ministers held a Retreat in Bagan, Myanmar from January 16-17. Philippines Secretary of Foreign Affairs Albert del Rosario called on ASEAN to “maintain regional solidarity” in response to China’s imposition of an ADIZ and new fishing regulations in the South China Sea.

“Clearly, in addition to unilateral measures to change the status quo and threats to the stability of the region,” del Rosario stated, “these latest developments violate the legitimate rights of coastal and other states under international law, including UNCLOS, and more specifically the principles of freedom of navigation and overflight, and is contrary to the ASEAN-China Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea.”

The ASEAN Ministers “expressed their concerns on the recent developments in the South China Sea. They further reaffirmed ASEAN’s Six-Point Principles on the South China Sea and the importance of maintaining peace and stability, maritime security, freedom of navigation in and overflight above the South China Sea.”

The ministers repeated ASEAN’s standard line that all disputes should be resolved by peaceful means in accordance with international law and that all parties should show “self-restraint in the conduct of activities.” The ministers declined to be specific and took no further action.

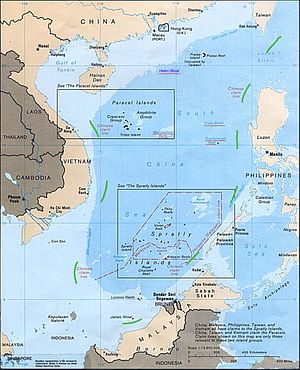

Third, on January 20 a PLAN flotilla comprising three ships, the Amphibious Landing Craft Changbaishan, and two destroyers, Wuhan and Haikou, left the naval base on Hainan to commence annual naval exercises in the South China Sea. The flotilla first conducted drills off the Paracel islands including amphibious landings “on every reef guarded by China’s navy,” according to the commander of the flotilla.

The flotilla then sailed south to the Spratly islands. On January 26 the Chinese media reported that when the ships reached James Shoal eighty kilometers off Sarawak, PLAN sailors conducted an oath taking ceremony vowing to safeguard China’s sovereignty and maritime interests.

The following day Qin Gang, a spokesperson for China’s Foreign Ministry, reiterated China’s “indisputable sovereignty” over James Shoal.

However, when Admiral Tan Sri Abdul Aziz Jaafar, the Chief of the Malaysian Navy, was interviewed by the New Straits Times on January 29 about the PLAN activities at James Shoal, he denied they took place.

According to Admiral Aziz, “There has been no act of provocation on the part of the Chinese or threat to our sovereignty as they are conducting their exercises in international waters” one-thousand kilometers away. Admiral Aziz was apparently referring to naval exercises conducted previously by the aircraft carrier Liaoning and its escorts.

This is the second time in two years that PLAN warships have visited James Shoal to assert Chinese sovereignty claims. On both occasions Malaysian authorities have denied any knowledge of Chinese activities. This raises questions about the veracity of Malaysian accounts, deficiencies in Malaysia’s maritime domain awareness capacity, or whether Malaysia ordered its navy out of the area to avoid any incident.

Fourth, the Asahi Shimbun reported on January 31 that a draft ADIZ for the South China Sea had been drawn up by air force officers at the working level at the Air Force Command College and submitted to the government in May 2013. The draft ADIZ reportedly covers the Paracel islands and some of the South China Sea. The Japanese report stated that Chinese officials were still deliberating on the extent of the ADIZ and the timing of the announcement.

Immediately after the Asahi Shimbun report was published it was dismissed by China’s Foreign Ministry. A spokesperson declared “generally speaking, China does not feel there is an air security threat from ASEAN countries” and therefore does not feel a need for an ADIZ.

It should be recalled, however, that in November last year when China announced its ADIZ in the East China Sea, a Ministry of National Defense spokesperson affirmed that “China will establish other Air Defense Identification Zones at the right moment after necessary preparations are completed.”

Fifth, in February, high-level United States officials became more assertive in opposing China’s ADIZ and territorial claims in the South China Sea. For example, on February 1, Evan Medeiros, Director for Asia at the National Security Council, stated in an interview, “We oppose China’s establishment of an ADIZ in other areas, including the South China Sea. We have been very clear with the Chinese that we would see that as a provocative and destabilizing development that would result in changes in our presence and military posture in the region.”

On February 5, Daniel Russel, Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs, stated in testimony to the House Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Asia and the Pacific that China should refrain from establishing other ADIZs in the region.

Russel also said, “any use of the ‘nine-dash line’ by China to claim maritime rights not based on claimed land features would be inconsistent with international law” and that China’s “pattern of behavior in the South China Sea reflects an incremental effort by China to assert control over the area contained in the so-called ‘nine-dash line’.”

Finally, Russel provided the strongest U.S. endorsement of the Philippines’ action in taking its territorial dispute with China to arbitration. Assistant Secretary Russel, “We fully support the right of claimants to exercise rights they may have to avail themselves of peaceful dispute settlement mechanisms. The Philippines chose to exercise such a right last year with the filing of an arbitration case under the Law of the Sea Convention.”

The two long-term trends include new U.S. assessments of the future balance of power in the Asia-Pacific and continued Chinese maritime modernization.

During January and February, three high-level U.S. officials proffered sober assessments of the changing balance of power in the Western Pacific.

On January 15, Admiral Samuel Locklear, Commander U.S. Pacific Command, was quoted by Defense News as stating, “our historic dominance that most of us… have enjoyed is diminishing, no question.” Admiral Locklear was referring to the rise of China’s naval power that would take time to eventuate. He concluded, “That’s not something to be afraid of, it’s just to be pragmatic about.”

In late January, Frank Kendall, Deputy Undersecretary of Defense for Acquisition and Technology, stated that U.S. military technological superiority is being “challenged in ways that I have not seen for decades, particularly in the Asia-Pacific Region.” He cited China’s military modernization and shrinking U.S. defense budgets as the main causes.

On February 4, James Clapper, Director of National Intelligence told a hearing of the House Intelligence Committee with respect to China, “They’ve been quite aggressive about asserting what they believe is their manifest destiny, if you will, in that part of the world. “ Clapper noted that China’s “very impressive military modernization” was designed to address what China views as U.S. military strengths.

According to testimony by the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) to the U.S. China Economic and Security Review on January 30, “The Chinese navy has ambitious plans over the next 15 years to rapidly advance its fleet of surface ships and submarines as well as maritime weapons and sensors.” The ONI reported that China laid down, launched or commissioned more than 50 naval ships in 2013 with a similar number planned for this year.

At the same time, it was reported that China has begun construction a second aircraft carrier which it hopes to launch in 2018. Security analysts believe that China plans to operate a carrier battle group in the “far seas” by 2020. There were also reports that China was building a hypersonic missile capable of penetrating the U.S. missile defense system.

In an analysis released in early February, IHS Jane’s estimated that China’s defense spending would reach nearly $160 billion in 2015, up from $139 billion spent in 2013. According to Deputy Undersecretary Kendall, “Overall, China’s military investments are increasing in double-digit numbers each year, about 10 percent.”

China continued to make similar advances on the paramilitary front. On January 10, a new 5,000 tonne ship was commissioned into China Coast Guard South Sea Fleet and stationed at Sansha City on Woody island in the Paracels. The China Ocean News reported on January 21 that the new vessel would commence regular patrols in the South China Sea to protect China’s maritime interests and provide a “speedy, orderly and effective emergency response to sudden incidents at sea.” Also on the same day, the Global Times and Beijing Times reported that China was building a 10,000-ton marine surveillance ship, the largest of its kind in the world.

Current short-term and long-term security trends appear likely to exacerbate tensions over territorial disputes in the South China Sea. The Philippines continues to engage in a war of words with China, while China continues to invest in Second Thomas Reef by stationing warships in the area. Differences in approach between the Philippines and Malaysia make it unlikely the four claimant states can reach a common position for ASEAN to endorse. ASEAN itself appears unable to reach a consensus that Chinese fishing bans in the South China Sea, coupled with the possible imposition of a Chinese ADIZ, are security issues affecting the whole of Southeast Asia.

China is continuing its build-up and modernization of both PLAN warships and paramilitary Coast Guard vessels. The former continue to conduct military exercises in areas where China’s nine-dash line overlaps with the Exclusive Economic Zones of claimant states. The latter are increasing in size thus enabling them to patrol and remain on station in the South China Sea for longer periods.

The current proactive U.S. challenge to China’s nine-dash line claim and opposition to any ADIZ in the South China Sea is likely to meet Chinese political, diplomatic and possibly military resistance in the form of challenges in contested waters. In the long-term, China’s naval modernization and expansion will result in the relative decline of U.S. naval primacy in the Western Pacific.