As Diplomat readers might be aware, China released a new official map of its territory. As far as Beijing’s provocative moves go, this one was … actually not too bad compared to China’s relatively recent decisions to impose an air defense identification zone (ADIZ) over the East China Sea or move oil rigs into Vietnam’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ). All Beijing did was publish a new map. This map has caused concerns among China’s neighbors in the South China Sea and even India (but nothing profoundly new in either case). Here on Flashpoints, Harry Kazianis called China’s approach “mapfare.” There is certainly truth in this description. By publishing these maps, Beijing continues to push its version of the facts on the ground, which it then enforces with declarations like the ADIZ, brazen resource exploration, and coast guard patrols (the Philippines became all too aware of this in 2012 in the Scarborough Shoal). One major curiosity with China’s official maps continues to be its audacious nine-dash line claim (now officially ten dashes for those of you keeping count). Why won’t Beijing just convert its dashes into a continuous maritime border?

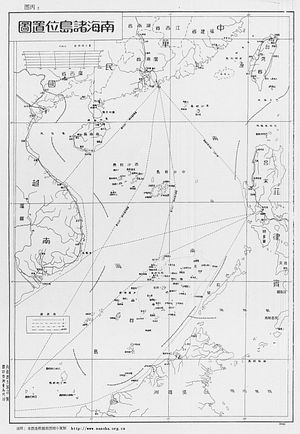

First, what are the benefits to Beijing of maintaining nine (or ten) dashes instead of a continuous line? Well, in order for there to be any benefit at all, maps would have to matter in the first place. I would argue that they certainly do in the Asia-Pacific. Each of the maritime claimants in the South China Sea comes to the table with their own map of the region. China’s claim to Asia’s cauldron (as Robert Kaplan puts it) is by far the most capacious and substantiated with ten dashes dating back to maps used by the Kuomintang government of the Republic of China in 1947. As others have noted, the primary advantage of these dashes is a degree of calculated ambiguity. According to Beijing, the dashes do not represent an inviolable sovereign claim to the entirety of the area demarcated by the dashes but in reality represent the maximum extent of Chinese control over the region.

This is a subtlety that often goes unappreciated in contemporary debates on China’s claim to the South China Sea. By maintaining its dashes, Beijing actually sees its position on its maritime claims as conciliatory and open somewhat to negotiation with other South China Sea states. One account of a Track II exchange between Western and Chinese scholars in 2009, recounted by Carl Thayer, states that “if nations which made claims for extended continental shelves withdrew such claims, there would be several areas within the dotted line might be amenable to joint development,” according to Chinese scholars.

While realities have changed since these assumptions were made in 2009, the basic ambiguity of the dashed-line claim persists. The United States has come out against China’s dashed maps, arguing that such claims have no basis in international law, including UNCLOS, which uses land features and the continental shelves as the basis for establishing EEZs and which China ratified in 1996. In the meantime, China has not converted its dashes into a line or even attempted to recreate its East China Sea ADIZ in the South China Sea as both of these actions would cause Beijing to lose the ambiguity of its territorial claims with little benefit. With the status quo of its dashed claim, one can imagine a South China Sea in which China succeeds with a combination of assertive “salami slicing” and bilateral diplomacy, resulting in a South China Sea in which China doesn’t control the entirety of its dashed-line claim but a majority of this area. This approach actually allows Beijing to gain control of territory it controlled historically without appealing merely to history (thereby making its claim look ever more ridiculous in the face of international law, specifically UNCLOS). In summation, it matters profoundly that China currently chooses to claim the entirety of the South China Sea with a dashed line instead of a continuous one.

The historical nature of the dashed-line claim is precisely what makes it a particularly audacious territorial claim. As Zach Keck noted, “allowing China to establish the principle that states can claim territory based on what their country has at times controlled would be disastrous for the simple reason that borders have been fluid throughout history.” China’s dashes aren’t quite a border. They do not state what China has but rather what China ought to have once the South China Sea’s disputes are filed away. It’s not a neat approach to diplomacy in the South China Sea, but don’t expect to see this basic aspect of China’s “mapfare” strategy change anytime soon.

Beijing’s dashes are here to stay.