In the late 1930s a proposal known as the Kimberley Plan was put to the Australian government for the relocation of persecuted European Jews to the Kimberley region of North West Australia. Although the plan attracted considerable public support it was ultimately was rejected by Prime Minister John Curtin on the grounds that he would not “depart from the long-established policy in regard to alien settlement in Australia.” (European Jews were deemed not to meet the criteria of the White Australia Policy.)

We can only speculate how this plan would have affected Australia but, anti-Semitic conspiracy theorists aside, most of us would envisage an overwhelmingly positive regional development for the Kimberley, benefiting the country as a whole. Not to mention saving a great number of lives.

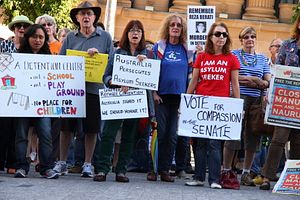

Despite lessons from the past, there is still a strong narrative in Australia that demonizes people seeking asylum as a clique of cagey opportunists “queue jumping” to leech off the Australian taxpayer. Realistically, though, one would expect refugees to have a great desire to contribute in exchange for their safety.

The two major political parties in Australia have fostered a public debate centered on the concept of “deterrence,” allowing them both little room to propose anything bar the next round in a game of one-upmanship to see who can offer the toughest policies on asylum seekers. There is little motivation to promote any ideas outside this current framework.

However, North West Australia continues to be a region in great need of development. It is sparsely populated, yet far from uninhabitable. Both of Australia’s major parties have floated policies to populate and develop the northern regions of Australia, acknowledging the advantages that this would bring to the country. (Plans can be found here for Labor, and here for the Liberals.)

While Australia has a number of people seeking asylum held in offshore detention centers on Manus Island and Nauru there is an obvious mutual benefit to creating a New Kimberley Plan. The government could offer refugees both sanctuary and opportunity, while simultaneously helping to create a prosperous region currently in need of development.

According to the government’s National Commission of Audit, the annual expenditure for offshore processing is currently A$3.3 billion ($2.9 billion), with forward estimates projecting this to rise beyond $10 billion (due to costs, not arrivals). Presently this expenditure is around $400,000 per detainee.

These figures highlight the absurdity of the “welfare narrative” in regards to people seeking asylum, particularly when these people would be very happy to become working taxpayers themselves.

Australia also has a number of asylum seekers within the country living in “community detention,” where they are not afforded work rights and forced to live on welfare. A parliamentarian from the National Party (in a permanent coalition with the ruling Liberal Party), Andrew Broad, identified this as a major flaw with the country’s processing procedures.

This issue did seem at one point to be heading towards resolution with the creation of the Safe Haven Enterprise Visa (SHEV), which would allow refugees to work in rural areas where there is a shortage of labor. It was also an acknowledgement by the government that there is a mutual benefit for Australia and those seeking asylum.

However, it seems as if the visa was a ruse, constructed solely to dupe mining magnate-cum-politician Clive Palmer into his votes in the Senate, and Broad into thinking the Cabinet valued his input.

If a genuine and accessible visa like the SHEV had been made available, it might have led to a positive outcome for refugees, regional areas, and the country as a whole. Particularly if there was a directed effort towards the northwest of the country.

Developing the northwest region of Australia would be a significant pivot towards South and Southeast Asia as major markets, expanding export opportunities away from simply relying on Chinese growth. With much lower transportation costs than from Australia’s traditional agricultural regions in the southeast Murray-Darling Basin, the ability to provide cheaper food to these regions in particular would be a great economic, diplomatic and strategic gain.

There is already some great success with agricultural industries along the Ord River in the Kimberley, and with around 60 percent of Australia’s rain falling above the Tropic of Capricorn the region has none of the water resource limits that the Murray-Darling Basin has, particularly for water-heavy crops like rice and cotton.

The opportunity to help build this region would undoubtedly be enthusiastically embraced by those fleeing persecution in exchange for safety and opportunity. One should never underestimate the goodwill of those who are treated with goodwill.

A historical “pioneering spirit” is a major component of Australia’s national narrative; however, the country is uncomfortable seeing anything similar in action today. The modern nation can only acquiesce to orderliness (which is why the concept of “the queue” resonates so well). Yet such views are ahistorical, whitewashing how regions and communities actually develop.

While restricting where people reside within the country may undermine its liberal principles, there are already models with in the country to work with. The working holiday visa, aimed at Western youth, requires holders to work for three months in rural areas in order to qualify for a second year long visa.

Attaching a three to four year regional requirement to a refugee resettlement visa would most likely be considered a bargain for those fleeing persecution.

However, this should also include a pathway to citizenship. Especially as their presence and efforts to develop the region would be of such great benefit to the country. After this period most people would be settled and invested in the region and a mass exodus would be unlikely.

Despite having produced a highly successful multicultural society, much of which was built on refugee resettlement after World War II, Australia’s national psyche still has an ingrained suspicion of “alien settlement” that severely clouds the government’s ability to make rational judgments.

Democracies today seem to simply react to and placate their loudest citizens, who are often the most negative and fearful. Politicians bypass the responsibility of explaining beneficial ideas to the public in favor of focusing on cynical election strategies. This makes it difficult implement plans of foresight.

The original Kimberley Plan was a missed opportunity for Australia, both in terms of the development of the north-west region of the country and its international standing as a moral global citizen.

Conventional wisdom makes it seem unlikely in the current political climate that Australia could transcend a public conversation welded to the concept of “deterrence.” However, with both major parties increasingly viewed with suspicion by the general public, space is opening up that could potentially change their collusion on this issue.

Grant Wyeth is a Melbourne based freelance writer. Follow him on Twitter @grantwyeth.