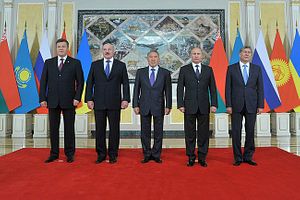

After many months of deliberations, a date has finally been set for the signing of the agreement through which Kyrgyzstan join the Kremlin-led Customs Union, ultimately resulting in the country becoming a full member of the Eurasian Economic Union alongside Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan and Russia. On December 23, Kyrgyz President Almazbek Atambayev will sign the agreement at a meeting of the Supreme Eurasian Economic Council, furthering deepening the country’s already extensive ties to Moscow.

The agreement ironically comes two days after the twenty-third anniversary of the signing of the Alma-Ata Protocol, which confirmed the dissolution of the Soviet Union and set the 15 republics that constituted the union on diverging paths. Nearly a quarter of a century after independence, the Kyrgyz Republic finds itself a signature away from joining what Slovak Deputy Prime Minister Miroslav Lajčák at a recent discussion at Stanford University referred to as the “Soviet Union 2.0.”

In many ways, the move represents a significant reversal from the early vision and hopes placed on the country. In the early 1990s, the Kyrgyz Republic was an oasis of liberalism and democracy in a region largely dominated by despotism. Early in his rule, President Askar Akayev built on these hopes when he presented to the world his vision for Kyrgyzstan becoming the “Switzerland of Central Asia.” Since then, however, the country has deviated from that goal and instead gradually fallen into the political and economic orbit of Moscow.

The pace of synchronization with the Kremlin accelerated significantly under Atambayev. Early in the year, the state approved the sale of the national natural gas company, Kyrgyzgas, to Gazprom for the token cost of $1 in exchange for promises of critically needed investments in its infrastructure network and a stable supply of natural gas. Not only have these promises been slow to materialize, but the sale prompted Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan’s difficult neighbor and primary supplier of natural gas to the southern half of the country, to abruptly halt its exports of gas to the country. The result has been that the city of Osh and the greater Fergana Valley, Kyrgyzstan’s second political and economic center, has been without gas for more than a half a year. The arrival of a cold winter brings with it the possibility that the heating shortage may spark yet another clash in this unstable region still healing from the scars of the ethnic riots that erupted in 2010 between Kyrgyz and Uzbeks. Bishkek’s hopes that a deepening integration with Russia would grant it relief from the constant antagonism of its neighbor has thus far proven to have been a miscalculation.

This year has also seen the closure of the Manas Air Base in the north of the country, which until then served as a logistics center for U.S. forces in Afghanistan. Any justification of the move on sovereignty grounds is weakened by the fact that Russia continues to operate its own military base in the country, which to any outside observer would appear to be a military outpost of a Kremlin reasserting its control over a former satellite.

The cooling of relations with the United States over this issue was part of a larger move away from the West and towards Russia. The increasing pro-Russian sentiments in the country manifest themselves in various forms, from Kyrgyzstan’s approval of Russian actions in Ukraine to the recent opening of a Putin-themed pub in the heart of the capital.

What does Kyrgyzstan have to show for this integration? Its energy security remains far from assured, facing a looming energy crisis that forced the government to plead with Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan for assistance to avoid what has the potential to become a political disaster. Economic integration with the EEU also far from assures the “powerful impetus for socio-economic development” Atambayev is hoping for. Kyrgyzstan’s closeness to the bloc is already causing it serious economic malaise. The Kyrgyz economy has suffered significant collateral damage as a result of Western sanctions on its primary trading partner. Growth has slowed, prices have risen significantly and the som has suffered a sharp depreciation, mirroring that of the ruble. Meanwhile, the Union itself faces grim economic prospects as Russia, its dominant economy, enters another recession and faces rapidly declining oil revenues. The market share of the Union’s member states in the global economy has declined annually with no reversal in sight.

Is there no viable alternative for Kyrgyzstan, as Atambayev claims? China’s New Silk Road Initiative certainly aspires to that role. Cooperation between China and Kyrgyzstan has increased significantly in recent years and should not be derailed for the sake of the perceived short-term benefits of joining the Kremlin’s economic bloc. Better to deepen ties with a China that seeks partners in Central Asia than a Russia that seeks protectorates.

Miguel Oropeza De Cortéz-Caballero is a Berkeley graduate and San Francisco based Asia Consultant with expertise in both East and Central Asia, where he has studied and worked.