America’s relationship with the People’s Republic of China began with containment in 1949: The victory of Mao’s communist forces in China’s civil war shocked Americans and created a fearful backlash of the monolithic advance of global communism. In 1972, the United States changed its policy of containing China and instead joined a quasi-alliance with it against the much more dangerous Soviet Union. When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1989, the U.S.-China relationship nonetheless remained generally positive, sustained by China’s relative liberalization, immense economic growth, and America’s distraction with interminable wars in the Middle East.

Now, in 2015, it is increasingly appearing as if T.S. Eliot was right and that “What we call the beginning is often the end.” “Washington is giving up on Beijing becoming a stakeholder in the present global order,” the Financial Times reports. China is “losing Washington,” declares Newsweek. “China has been ‘weaponized’ in U.S. domestic politics,” notes the National Interest. “Calls to punish China grow,” affirms Bloomberg. President Xi Jinping “is moving in the other direction, (away) from [the] constructive engagement” of China’s last two presidents, asserts the chairman of the House Committee on Foreign Affairs’ subcommittee on Asia and the Pacific. It is in this context that two prominent American scholars and diplomats have written a primer on how the U.S. should revise its grand strategy to keep a rising China down, in order to maintain American primacy in Asia and beyond.

For years, in fact, prominent scholars – such as John Mearsheimer of the University of Chicago – have called for America to balance against a rising China. They have made this appeal according to the abstract structural logic of international relations theory. The logic goes like this: American military primacy should be maintained at all costs, China’s rise threatens this primacy, so the U.S. should work to “balance” against – or, broadly, contain – a rising China by surrounding it with powerful American military capabilities, creating NATO-like adversarial alliances, isolating it economically, and, most recently, “imposing costs” when it does things the U.S. does not like.

The newest primer, “Revising U.S. Grand Strategy Toward China,” written by Robert D. Blackwill and Ashley J. Tellis and published by the prestigious New York-based Council on Foreign Relations, rehashes all of these “offensive realist” prescriptions (summarized by The Diplomat here), but with one difference: It does not own up to the logic of its position. Treating China according to the report’s recommendation would not force it to meekly back down, nor would it result in a simple realignment of the “balance of power.” Instead, it would create a new, volatile, zero-sum environment in which the U.S. and China would become rivals, the region would become polarized, arms races would flourish, and, inevitably, crises would ensue. Whether these crises would produce war no one can know, but the creation of such an environment is certain to make war far more likely. This is where “balancing” against China necessarily ends. John Mearsheimer has forthrightly acknowledged this to be the case, leading him to predict that the U.S. and China will fall into conflict. Blackwill and Tellis – and indeed, many other prominent advocates of balancing China – instead sustain a fiction that the U.S. can walk down the realist road to war without making great power politics tragic. This is mistaken and dangerous.

The Balance China Argument

According to Blackwill and Tellis, the preeminent objective of the U.S. should be to maintain, and increase, its power. With this as their premise, they deduce that growing Chinese power threatens the U.S. In response, the U.S. should balance against China in all the traditional ways: Exclude it from economic pacts, restrict its technology imports, and threaten it by surrounding it with powerful U.S. military forces and strong U.S. allies. The way to respond to a rising power is to try to push it back where it came from.

Blackwill and Tellis are not particularly interested in the distinctive or characteristic qualities of a rising China, because it is the structure of the international system that dictates their response. They write:

Although Chinese behavior may be “normal” for a rising nation, that does not diminish China’s overall negative impact on the balance of power in the vast Indo-Pacific region; nor does it reduce the crucial requirement for Washington to develop policies that meet this challenge of the rise of Chinese power and thwart Beijing’s objective to systematically undermine American strategic primacy in Asia.

There is, therefore, really only one solution: balance China.

China’s Probable Response

While Blackwill and Tellis do indeed advance an alternative grand strategy vis-à-vis China, their proposal is not “strategic.” They argue, “the United States should become more strategically proactive in meeting the Chinese challenge to U.S. interests and less preoccupied with how this more robust U.S. approach might be evaluated in Beijing” (emphasis added). However, strategy in its essence is about making decisions in a setting of interdependent choice: i.e. the success (or failure) of a strategy hinges upon how others react and respond. This is why renowned strategist Edward Luttwak has pointed out that strategy always has a paradoxical logic. Or as Lawrence Freedman has recently argued in his magnum opus, strategy is a dialectical process, not a static one. The adversary, we all should know, gets a vote, or, if we’re playing weiqi, a turn, too. A U.S. grand strategy toward China that does not seriously consider China’s likely response can only bet on luck to bring it success.

To be fair, toward the end of their report, Blackwill and Tellis do briefly discuss China’s likely responses. Oddly enough, they simply assume that China will choose to continue cooperation with the U.S. on a wide range of issues. But why assume China’s response to be so mild if the U.S. is blatantly and aggressively working to isolate it and keep it down? Here you see a much “nicer” China, one that would not “act in ways that damage its policy purposes and its reputation around Asia.” This image stands in sharp contrast to the other “China” that throughout the rest of the report is portrayed as bullying its neighbors and trying to replace U.S. hegemony. As Australian scholar Hugh White astutely observes, “their prescriptions assume what their analysis disproves: that China is not really serious about challenging US primacy after all.” Blackwill and Tellis insist, “Washington simply cannot have it both ways – to accommodate Chinese concerns regarding U.S. power projection into Asia through ‘strategic reassurance’ and at the same time to promote and defend U.S. vital national interests in this vast region.” Yet they do not explain why they can have it both ways – to balance against China while simultaneously expecting Chinese diplomatic cooperation.

Indeed, a concerted American effort to either “impose costs” or “contain” Chinese power today would reinforce China’s deepest fears and prove Chinese hawks were correct all along, provoking the security dilemma in a most aggressive way. In response to the now strengthened hawks, and possibly to an outraged public, perhaps China would significantly increase its defense spending – something it is capable of doing as it currently spends only half of what the U.S. spends as a percentage of GDP. Perhaps it would begin building submarines “like sausages.” Perhaps it would begin a massive nuclear build up to deter the U.S., starting an arms race reminiscent of the Cold War.

Or perhaps in response China would pursue external balancing via formal military alliances, and here Russia is the most promising candidate. There are significant barriers to a Sino-Russian alliance including mutual distrust, bitter historical memories, weak economic ties, China’s non-alignment policy, and the two-nations competition for influence in Central Asia. But the proper strategic imperative could overcome all such obstacles. Already China and Russia have settled “all of their long-standing border disputes” and Russia is “pivoting” its economy towards Asia, The Economist reports. Whether China and Russia are given the incentive to “pivot” further toward one another – and thus shake the foundation of American primacy – is in large part up to the U.S. Balancing can work both ways. In sum: There is considerable uncertainty regarding how precisely China would respond – hence the vagueness of this section – but one thing can be counted on: China would act much more forcibly than many, including Blackwill and Tellis, seem to expect.

More fundamentally, the authors have an unsound view of China’s grand strategy, which for them is crystal clear: to replace U.S. hegemony in Asia. Although growing assertiveness in some aspects of Chinese foreign policy has unsettled certain Asian countries and lent some validity to this interpretation, it is premature to conclude that China is actually seeking to “dominate” the region. According to a recent survey of Asian strategic elites done by the Center for Strategic and International Studies, although only 11 percent of Chinese respondents favored a U.S.-led regional order, a similarly small number (17 percent) wanted a Sino-centric order. More than 40 percent desired to see “a new community of nations based on strengthened multilateral institutions and cooperation.” Moreover, more than half of Chinese respondents expect to see continued U.S. leadership in Asia over the next decade. In short, China’s future strategic orientation is still in flux, but Blackwill and Tellis see it as preordained.

The Realist Road to War

What is so frustrating, and perhaps paradoxical, about the growing chorus singing that the U.S. should lead a balancing coalition against China is that it fits flawlessly into prominent political science explanations for how major war occurs. According to the respected empirical scholarship of John Vasquez, for example, war is the outcome of a process, not a random or inexplicable event. Nations go down a “road to war” by making certain specific decisions. Each decision makes war more likely and reinforces the logic of conflict. Once you travel down this road for a while, war becomes difficult to prevent and easy to cause.

According to Vasquez, the “realist road to war” begins with a dispute, typically over territory. The U.S. has no direct territorial disputes with China, but by intervening in the disputes of others (from the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands in the East China Sea to Taiwan and the rocks of the South China Sea), this first condition is met. Next, one state “balances” against the other by building up its military and forming or strengthening regional adversarial alliances. The justification for this step along the road to war can vary, but it generally involves the language of deterrence, standing up to bullying, peace through strength, or in the case of Blackwill and Tellis, maintaining American primacy

Advocates of this stage two balancing tend not to peer too intently at the future, preferring to comfortably assume their nation’s stronger military position will dampen the dispute in question. But this is not what typically happens. Instead, the state balanced against responds with its own military buildup, which seeks to cancel out the first state’s relative gains. Following America’s fireworks show in Iraq in 1991 and threatening display of force against China during the 1996 Taiwan Straits Crisis, the Chinese government has pursued rapid military modernization for just this reason. Balancing and counterbalancing, in turn, result in three new elements of competition: increasing polarization – e.g., other states in the region are increasingly forced to choose between America or China – arms races, and deepening rivalry.

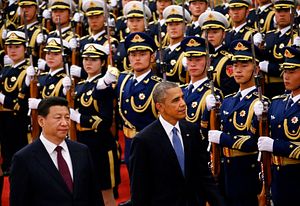

In this context, both sides are likely to make threats or demonstrations of resolve in order to strengthen the credibility of their deterrent or demonstrate the gravity of their position. From such actions crises develop. In the U.S.-China relationship the most serious of these was the 2001 EP-3 Incident in which Chinese and American military planes collided, but since then a whole series of incidents has occurred between Chinese and American naval forces – for example, the 2009 Impeccable incident in which a collection of Chinese vessels harassed the U.S. Navy surveillance ship Impeccable as it was gathering intelligence off the coast of Hainan Island. These crises, even when resolved peacefully, vindicate the hawks of both sides, reinforcing visions of the other’s aggressiveness and, even more importantly, granting them additional influence among decision makers. This stage of the process has not yet been reached in the U.S., but the 2016 presidential election, in which every contender other than Rand Paul is likely to take a more hawkish position on China than President Barack Obama has, would provide a perfect opportunity for such a new resolution against compromise to congeal, perhaps concluding with the appointment of scholars like Blackwill and Tellis to top government posts.

In the final stage on the path to war, a new crisis develops – call it Senkaku, Scarborough, or a South China Sea ADIZ – neither side backs down as opinions of hawks now dominate the intellectual decision-making process, and war is the outcome. A version of this process happened in 1914. It is not unthinkable that it would happen in 2015.

Suicide for Fear of Death

The way to avoid a U.S.-China conflict is to step off the road to war. The first step off this road should be the admission that a concerted effort to balance against or contain China is a sure recipe for inviting a forcible response from Beijing and bringing conflict closer to the region. The prescriptions of Blackwill and Tellis are a call for suicide for fear of death, or more specifically, they risk suicide for fear of a world in which the U.S. is not the dominant power. But this fear is misplaced.

There is good news and bad news for analysts who fear China’s rise. The bad news is that whether China will rise or not ultimately depends on its own domestic development and much less on what others do. To use one of Joseph Nye’s favorite phrases, “only China can contain China.” The good news is that even without U.S. primacy in Asia, it would still be very difficult, and most likely impossible, for China to dominate the region given the presence of multiple major powers, nuclear weapons, and the high tide of nationalism. To put it another way, Blackwill and Tellis’ report calls for expending enormous resources and running grave risks to prevent something that is not likely to happen. Needless to say, this does not sound like a very auspicious “revision” to U.S. grand strategy.

Jie Dalei is an assistant professor at the School of International Studies of Peking University. Jared McKinney is a dual-degree graduate student at Peking University and the London School of Economics.