Sino-Russian relations appear to be flourishing. As Moscow has become locked in conflict with the West over the crisis in Ukraine, it has moved closer towards its long-time international partner, Beijing. Highlights of Sino-Russian cooperation in 2014 included the conclusion of large-scale energy deals, the initiation of ambitious bilateral projects in the economic and financial sectors, joint military maneuvers, and the announcement of further arms deals.

Behind the burnished diplomatic façade, however, many of these projects have in fact been stalled since shortly after their inception. In particular, the massive bilateral gas export agreement reached in May 2014 has made little progress towards implementation, and its precise stipulations remain shrouded in mystery.

Russia’s brazen violation of Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity – which contradicts principles that both Moscow and Beijing had thus far jointly advocated on the international stage – was received coolly by Chinese government officials. Russia’s actions did, however, garner praise from leading state-controlled Chinese media, at a time when China is vocally advancing various territorial claims of its own in the East and South China seas. Moscow’s intervention in Ukraine resonated with Beijing’s recent territorial assertiveness, but this in itself is unlikely to promote closer Sino-Russian strategic interaction, since both countries have historically had intricate territorial disputes between themselves.

Central Asia

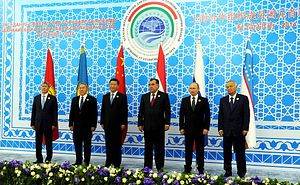

But by far the greatest stumbling block for the two countries’ further rapprochement has been the nature of their interaction in Central Asia. In almost every other field of Sino-Russian relations, the Ukrainian crisis has served to further solidify bilateral cooperation; with regard to Central Asia, however, it has raised various thorny questions. Sino-Russian tensions in the region have been simmering under the surface for a number of years. Through its relentless penetration of the region’s economies, China has rapidly broken the economic and political hegemony that Russia had enjoyed there since the mid 19th century. China has already become the largest trading partner of all five Central Asian republics; its total trade with the region is now more than double that of Russia. Flooding the region with investments, China has built major oil and gas pipelines across Central Asia that cut through Russia’s long-standing stranglehold on the region’s energy exports. The Central Asian countries now provide Beijing with around 40 percent of its gas imports. Last September, the Tajik and Chinese governments launched the construction of a new gas pipeline that turned Tajikistan into the latest transit country for Central Asian gas supplies to China.

Moscow has looked on warily as Beijing consistently extended its influence in Russia’s former dependencies. While Russia has been co-opted to participate in some of China’s economic projects in the region, it has for the most part been sidelined. The final departure of U.S. forces from their one remaining military base in Central Asia – Manas Air Base in Kyrgyzstan – in June 2014 means that Russia now has the privilege of facing China’s forays into Central Asia on its own. Already as early as January 2010, the incipient tension between Moscow and Beijing was reflected in leaked confidential comments by China’s former ambassador to Kazakhstan, Cheng Guoping. Cheng underlined that, in Central Asia, China and Russia were rivals on the economic front, “and again asserted that Russia’s reaction will not force [China] to limit its regional cooperation.” Cheng also predicted that “the growth of Chinese influence will break the Russian monopoly in the region.” At the time, Cheng not only “expressed a positive view of the U.S. role in the region,” but also suggested that NATO should take part “as a guest” at talks on the Shanghai Cooperation Organization.

The Ukraine crisis has now brought these simmering tensions into starker focus. Many prominent realist commentators have described Russia’s actions in Ukraine as the foreseeable reaction of a beleaguered great power to a hostile West’s increasing intrusion into one of its core spheres of influence. But if we give credence to the realist depiction of Russia as a state that would inevitably resist any encroachment on its perceived spheres of influence, we should have expected a similar reaction to China’s persistent undermining of Russian hegemony in Central Asia – another one of the Kremlin’s traditional core spheres of influence.

This is all the more perplexing since the scenario in Central Asia is strikingly similar to that in Ukraine. Like in Crimea, Russia has military bases and troops stationed in the region (in both Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan), which it could easily resort to for invasive or disruptive purposes. The Central Asian republics contain sizable ethnic Russian minorities. Additional Russian legislation that was passed in late April 2014 essentially makes all ethnic Russians in bordering states eligible for Russian citizenship, which could possibly be used as a further justification for intervention.

In the case of Kazakhstan, the percentage of ethnic Russians among the population is nearly 22 percent (proportionally larger than in Ukraine). This number reaches 50 percent in the northern parts of the country. Russian nationalists like Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn have in the past claimed northern Kazakhstan as part of historical Russia, and there has already been an attempt by pro-Russian separatists to seize an area in the north of the country: In late 1999 and early 2000 a small group of insurgents led by a Moscow resident planned to take over the local administration of the city of Oskemen near the Russian border and appeal to Moscow to incorporate the area into the Russian Federation – essentially the same scenario that could now be witnessed in eastern Ukraine. Their efforts were nipped in the bud by the Kazakh authorities.

Ominous References

Kazakhstan and its Central Asian neighbors have less cultural and historic significance for the Russian leadership than Ukraine, but the case of Russia’s military meddling and subsequent intervention in Georgia in 2008 indicates that this would not necessarily render them less likely targets for an armed incursion. In his March 2014 speech marking the annexation of Crimea, Vladimir Putin made ominous references to “the Russian nation” as “the biggest ethnic group in the world to be divided by borders” and “the aspiration of the Russians, of historical Russia, to restore unity.” In a foreign-policy speech to the assembled Russian diplomatic corps on July 1, Putin further announced that Russia “will continue to actively defend the rights of Russians, our compatriots abroad, using the entire range of available means.” Putin also made it clear how boundless this ambition might potentially be, pointing out that “when I speak of Russian people and Russian-speaking citizens I am referring to those people who consider themselves part of the so-called broad Russian world, not necessarily ethnic Russians, but those who consider themselves Russian people.” The underlying mindset and ambitions reflected in these statements are likely to complicate the long-term harmonization of Beijing’s and Moscow’s interests in the Central Asian region. In the long term, Beijing will find it increasingly hard to turn a blind eye to Russia demanding a power of guardianship in what has already become a crucial new sphere of influence for China.

What is more, as in the case of Ukraine Vladimir Putin has expected the Central Asian states to become part of a Moscow-dominated regional bloc modeled after the EU, the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU), which was officially inaugurated in a lackluster ceremony in January. Kazakhstan formally joined Putin’s pet project in May 2014, while Kyrgyzstan is scheduled to join it this month. In the Ukrainian case, disputes over whether the country should join a free trade arrangement with the European Union had been the initial trigger of the domestic political crisis and the conflict with Moscow, which insisted on Kiev’s inclusion in the EEU – joint membership in both formats, including overlapping customs barriers, was considered impossible.

In Central Asia, nearly identical dynamics have been at work. The prospect of creating a deeper economic (and ultimately political) union along the lines envisaged by Putin is increasingly being undermined by the Central Asian states’ rapidly intensifying economic integration with China (just as, in the case of Ukraine, it had been undermined by the prospect of a deepening economic integration with the EU). This tendency has been further accelerated by Beijing’s efforts to involve the Central Asian states in an extensive set of plans to develop Eurasian infrastructure, energy, and trade links between China’s Western provinces and European markets, which was first announced under the label “New Silk Road Economic Belt” during President Xi Jinping’s trip to Central Asia in September 2013. It now forms an integral part of the so-called “One Belt, One Road” initiative, one of Beijing’s most important foreign policy goals in the near future. Russia was largely bypassed in this initiative, which is aimed in large part at strengthening China’s ties with the Central Asian states.

Although China has since tried to dispel Moscow’s concerns, insisting that the plan is not directed against Russia, there can be little doubt that Putin’s Eurasian Economic Union and China’s wide-ranging plans to further expand its economic reach in Central Asia are two mutually incompatible projects.

This has become particularly evident in the case of Kyrgyzstan, which for years has generated a substantial portion of its GDP through the import and re-export of Chinese consumer goods into other former Soviet republics, particularly Kazakhstan. By 2009, the Dordoi Bazaar, the country’s largest re-export marketplace for Chinese goods, had an estimated annual turnover of over $2.9 billion, compared to an official annual foreign trade turnover of $6.5 billion for Kyrgyzstan as a whole. This lucrative shuttle trade which, at its peak, was estimated to be worth almost twice Kyrgyzstan’s GDP, took a hit after neighboring Kazakhstan joined a Moscow-led customs union (the predecessor of the EEU) in 2010. Following Kyrgyzstan’s scheduled accession to the EEU this month, its re-export trade with China will inevitably fall foul of the higher external tariff barriers mandated by the organization. Bishkek’s decision to join the EEU has already caused apprehension among leading Chinese investors in the country. Overall, however, in the face of China’s continuously growing economic penetration of the region, the EEU’s prospects of long-term success in Central Asia are increasingly doubtful. Unsurprisingly, China’s alternative suggestion to create a free trade zone within the format of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization has met with a cold reception from Moscow.

Russia has so far done little to curb China’s expansion in Central Asia and to resist its own displacement in the region, but it is doubtful that it will pursue such a passive policy indefinitely. For the moment, Moscow has an interest in accommodating Beijing. But if it ever deems it necessary, Russia could easily and rapidly destabilize the Central Asian states – at the expense of China, which now has a huge stake there and tries to keep the peace in the region. Should Russia embark on a Ukrainian-style intervention in Kazakhstan, for instance, this could seriously endanger the security of China’s overland oil and gas supplies. Since a large portion of China’s energy imports now pass through Kazakhstan, Russia could gain control over these flows. Moscow could also assume control of the volatile border with Xinjiang, where Uighur factions are struggling against Beijing’s rule. Kazakh diplomats have long reported that Russian officials habitually remind them that Moscow could sow serious trouble among the country’s large Russian minority if the government in Astana ever chose to stray too far from Moscow’s preferred line on various policies.

Muscle Flexing

Apprehension about Russia’s intervention in Ukraine has been palpable among Central Asian officials since Russian troops were first seen occupying strategic points on the Crimean peninsula. Kazakhstan’s President Nursultan Nazarbayev was initially steadfast in his support for Putin’s actions in Ukraine, being one of the only world leaders to have joined Russia in labeling Ukraine’s Euro-Maidan revolution a “coup.” Kazakhstan was also one of the few states to recognize the disputed referendum in Crimea.

In subsequent months, however, Astana backtracked and appeared to retract its initial recognition of the Crimean takeover. Kazakh concerns about Russia’s potential future moves were magnified in late August 2014, when Vladimir Putin – in response to a question on whether Kazakhstan might experience “a Ukrainian scenario” in the future – made statements that seemed to question the legitimacy of Kazakh statehood. Kazakhstan’s President Nazarbayev, he said, had “done a unique thing. He created a state on a territory where there had never been a state; the Kazakhs have never had any statehood of their own, he created it.” Putin added that he was confident that the Kazakh people recognized that it was beneficial for them “to remain in the sphere of the so-called greater Russian world” in the medium and long term. Apparently in response, Nazarbayev warned the following day that “Kazakhstan has every right to withdraw from membership in the Eurasian Economic Union. Astana will never be part of organizations that pose a threat to the independence of Kazakhstan.” Immediately afterwards, during Independence Day celebrations in neighboring Uzbekistan on September 1, Uzbek President Islam Karimov very pointedly demanded respect for state sovereignty and borders and a rejection of the use of force, in comments clearly aimed at Russia. The Central Asian leaders’ concerns about Moscow’s muscle flexing are prone to further expedite their rapprochement with the new regional power broker – Beijing.

For the moment, the West’s hostile reaction to Russia’s actions in Ukraine and the dire economic situation in Russia seem to act as a restraint on Moscow’s assertiveness in its near abroad. At present, these factors serve to discourage any additional territorial claims the Kremlin might have been tempted to raise. Eyeing further economic expansion in Central Asia, China undoubtedly appreciates this no less than the West does. But once Russia has weathered its current economic crisis, it is likely to eventually reassert its influence in Central Asia in no less forceful a manner than it did in Ukraine. This would run directly counter to Chinese interests in a region that has of late come to be of supreme strategic importance for Beijing.

For many years, Moscow has looked the other way as China rapidly extended its influence in Russia’s former dominions. But the many conspicuous similarities between the situations in ante-bellum Ukraine and present-day Central Asia raise questions as to how long China will be able to retain this privileged status in the eyes of the Kremlin. Already prior to the Ukraine crisis, Chinese and Russian interests in the region had become increasingly incompatible. Following Russia’s intervention in Ukraine and the rationale Moscow has presented to justify it, this divergence of interests is only set to grow.

Björn Alexander Düben is an Assistant Professor at the School of International and Public Affairs at Jilin University and teaches Security Studies, Diplomacy and Intelligence at King’s College London. He completed a PhD on China-Russia relations at the London School of Economics & Political Science (LSE), following graduate research on the same subject at the University of Oxford.