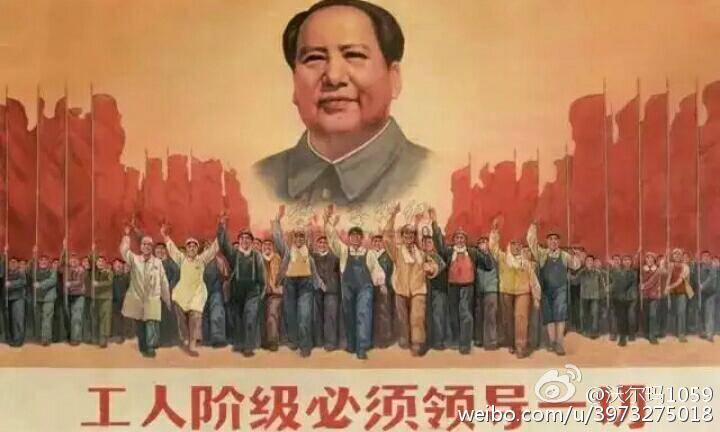

When Zhang Jun, a 44-year old electrician at Wal-Mart (China) Investment Co., Ltd. in Shandong, east of Beijing, shared his association’s Weibo blog, featuring a Mao-era propaganda poster, he was trying to make a point.

In it, Mao beams over a group of mobilized workers. A caption reads: “The working class must lead everything.” Zhang is not a fan of Mao, or his trade unions, but he is trying to revive a Maoist dictum in a cat-and-mouse game with both China’s only legal trade union and his capitalist bosses in Bentonville, Arkansas.

Zhang’s loosely defined movement — the “Wal-Mart China Staff Association” — is neither huge nor high profile, and it doesn’t have a national political agenda. But the activists involved are no longer just focused on specific workplace grievances. Instead, they are fighting for workers’ rights to organize a real union with teeth: namely, collective bargaining power.

And while this transition is standard in the history of labor movements around the world, the fight of activists like Zhang in China is unique. They are trying to re-code the only union that’s allowed to exist in China, the so-called All-China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU). As a socialist institution, it was a conduit for the Communist Party to its large working class, as opposed to a trade union with collective bargaining power that represents workers’ interests. As a result, the ACFTU has mostly stood on the sidelines as protests and collective strikes have intensified and increased in frequency.

Prompted by signs that Beijing’s central leadership is urging the 200-million member ACFTU to reform, Zhang and a small cadre of like-minded organizers are applying pressure on the ACFTU from below — demanding democratic elections of the grassroots layers of the ACFTU at their respective Wal-Mart stores, which they claim have been illegally controlled by Wal-Mart’s management since unionization in 2006.

Wal-Mart is the latest frontier in a series of incidents where pioneers like Zhang Jun, who are experienced in activism and educate other workers on their labor rights, are pushing the envelope to apply pressure on the ACFTU to reform from below.

“In five to ten years, (Chinese) workers will be able to reclaim the union through collective bargaining, and that [would be] the biggest national union on earth with bargaining power,” says Han Dongfang, founder and executive director at China Labor Bulletin, a non-governmental organization in Hong Kong.

Growing labor activism could also make it harder for employers to manage costs as China’s economy slows. Wal-Mart itself is already grappling with such pressures elsewhere: its share price is yet to recover from last month when it reported that higher wages had hurt its bottom line. That’s largely a North American problem – the retailer has more than 6,000 stores there – but it still has 100,000 employees in about 400 stores in China, 19 years after entering the Chinese market.

Wal-Mart also became the first foreign company to accept unionization in China in 2006. But since unionization, the ACFTU has been standing on the sidelines, say Wal-Mart labor activists. Although several municipal-level branches of the ACFTU convinced Wal-Mart in 2008 to raise its wages by eight percent both in 2008 and 2009, Wal-Mart labor activists claim that otherwise Wal-Mart’s wages have stagnated since unionization.

This is because, Wal-Mart activists argue, the enterprise union committees are controlled by management-appointed representatives, so-called “yellow union committees.” China’s labor laws and ACFTU policy theoretically allow workers to directly elect their own representatives in these enterprise unions, but in practice, Wal-Mart’s activists claim that the elections are held in secret, with Wal-Mart appointing its own representatives.

The company wouldn’t comment on the election of its ACFTU locals, or on specific labor disputes. But Marilee McInnis, Director of International Corporate Affairs at Wal-Mart, says that the company’s policy is to “protect the interest of associates [i.e. employees] while promoting the sustainable development of the company, provide competitive wages, and have resources in place to train and develop associates.”

There are signs that the ACFTU itself may be primed to change from the highest levels in Beijing. In 2013 Chinese president Xi Jinping explicitly asked the ACFTU to “protect workers’ interests and promote social justice to win public trust and support,” and to set up trade unions as a genuine “home for employees.”

Local governments, in particular in Guangdong, have recently introduced new regulations that allow for “collective consultation,” the Chinese version of collective bargaining. And while there are still many caveats to these regulations, it is a move in the direction of strengthening the position of workers.

But Wal-Mart’s activists do not want to wait for the slow-moving ACFTU to reform.

Enter the Staff Association, which Zhang Jun founded in mid-2014. By day, Zhang works as an electrician at Wal-Mart’s Yantai store, in Shandong province in China’s northeast. In his spare time, through his association, he advises Wal-Mart workers across China on how to put local employees truly in charge of their ACFTU enterprise union, using lessons he learns at workshops organized by labor groups in Hong Kong.

In doing so, he’s taking on both Wal-Mart, and the Beijing-induced presumption that the ACFTU obey its whims. “Years of anger over Wal-Mart’s illegal suppression and manipulation of the trade unions, and exploitation of employees, is now bursting out,” writes Zhang on the association’s micro-blog.

Labor activists in China say that Wal-Mart has responded to such efforts by firing activists like Wang Shishu, a Wal-Mart worker in his mid-50s. Wang lost his job in 2012 after organizing workers in Shenzhen, the mainland boomtown next to Hong Kong, to demand better wages.

If firing activists is part of a strategy, it may be backfiring by placing the issue of workers’ rights squarely in front of Chinese courts. Wang sued Wal-Mart in 2012 for wrongful dismissal and won his job back. Then he lost his Wal-Mart job again after resuming his labor activism, according to a China Labor Bulletin account. He is now taking Wal-Mart to court again, alongside Yu Zhiming, one of the few democratically elected worker representatives at a Shenzhen store. Yu was dismissed in March 2015 after his enterprise union committee opposed a new Wal-Mart rule that would simplify dismissals.

Duan Yi, a Guangdong-based labor lawyer, says that in the past six years he has helped over 100 Wal-Mart employees who have lost their Wal-Mart jobs after attending labor rights workshops or marching in protests for things like higher wages. The “Wal-Mart union never spoke up when Wal-Mart laid off their employees in the past,” he says. But now, Wal-Mart is stuck between a rock and a hard place: outspoken Wal-Mart activists are demanding that the enterprise union be democratically elected, and Wal-Mart does not get a free pass to rid itself of them.

Now the battle has shifted to Wal-Mart’s Store 1059 in Shenzhen. Wal-Mart workers there are currently challenging the results of elections, claiming they are “yellow union committees.” Zhang Liya, a Wal-Mart activist in the Staff Association and senior employee at Wal-Mart’s store 1059, announced in September that he will put himself forward as candidate for the enterprise union’s presidency whilst also campaigning for democratic elections to be held. He actually thought it worthwhile to write an open letter to leaders of the ACFTU higher up, including the Shenzhen branch, for help, through the Staff Association; they say they haven’t heard back.

Navigating the murky waters of labor activism in China remains a delicate balancing act for pioneers like Zhang Jun. Earlier this year, ACFTU vice-chairman Li Yufu said in an interview with a political magazine that “hostile foreign forces” are infiltrating the Chinese labor movement, which “are attempting to wreck the solidarity of the working class and trade union unity with the help of some illegal ‘rights’ organizations and activists,” the Financial Times reported. Activists like Zhang are often assisted and trained by labor groups both inside and outside China. Although it is Zhang and his Staff Association’s aim to organize within the ACFTU, they also seek support from international labor organizations, such as China Labor Bulletin. Zhang has even been writing to the American trade union, the AFL-CIO. A new draft law for foreign NGOs that introduces a high level of state oversight of foreign NGOs will further complicate support that activists such as Zhang receive in China.

Labor lawyer Duan Yi believes that the Wal-Mart activists “should at least be able to achieve an elected labor union committee this year,” but he foresees that “those union members need more organization and training in the future, which they currently lack.” The next hurdle, Han of China Labor Bulletin says, will be better protecting local representatives once they are elected.

Wal-Mart may not care much about the China activists, says Anita Chan, a scholar on China’s labor issues and Wal-Mart’s in particular, but it “may have a wider impact within China.” Through the Staff Association, workers across China’s stores are following the developments at store 1059 in Shenzhen. Successful experiences are quickly shared among workers on social media, especially within organizations such as Zhang Jun’s.

Although the labor movement is still in its infancy, says Chan, “in a little over a decade, starting with scant awareness of labor rights and trade unionism as a vehicle for change, workers’ consciousness of the importance of collective representation in the form of democratically elected trade unionism is emerging.”

Zhang, the Staff Association founder, is hopeful: “Our cooperation can bring about extraordinary history, which is achieved through an accumulation of small things brought about by ordinary people like us.”

Linda van der Horst holds a Master’s degree in Modern Chinese Studies from the University of Oxford. She is a lawyer in the U.K. and currently a journalism fellow at the Munk School of Global Affairs. You can follow her on Twitter: @LindaXiaXian