The long rifle was the great weapon of its day … today this B-52 is the long rifle of the air age.

-Gen Nathan Twining, March 18, 1954

It seems increasingly likely that there will be a B-52 flyby for the retirement of both the B-1 Lancer and the B-2 Spirit. The venerable bomber, which first flew in 1952, remains the primary component of the USAF’s bomber force for both nuclear and conventional missions. Lacking the stealth of the B-2 and the speed of the B-1, the B-52 remains a frontline combat aircraft because of its exceptional range, unmatched versatility, and flexible payload options. It is debatable whether today’s aviation industry could re-create an airplane with this essential mix of capabilities, but a fully modernized B-52, in combination with the new Long Range Strike Bomber (LRS-B), would provide the USAF with an asymmetrical advantage over both China and Russia that neither is likely to match. Far from being obsolete, the Stratofortress could well serve into the 2050s, making an updated bomber well worth the effort and expense, and ushering in the B-52J Centuryfortress – the 21st century bomber.

Background

Oddly enough, it is the substantial increase in the military capabilities of both Russia and China that make the B-52 an attractive prospect again. China’s pursuit of a comprehensive anti-access/area denial (A2AD) capability has not only resulted in a threat to air operations, but a threat to airbases as well. China has over sixty military airfields just in the four military districts closest to Japan and Korea, some of which are hardened to a standard that no U.S. base has ever achieved. Matched against this are six U.S. fighter bases in Japan and Korea. All of the potential U.S. fighter bases are subject to overwhelming attack by ballistic missiles, cruise missiles, and combat aviation from a country that has more missiles, more aircraft, and the ability to rapidly and overwhelmingly mass effects against very few fixed U.S. targets. Combined with a major investment in ship-killing missiles, including the DF-21D antiship ballistic missile (the first of its kind), Beijing has the ability today to make it very difficult for the U.S. to operate aircraft or surface combatants in China’s front yard.

From a tactical standpoint, China clearly intends to negate the U.S. investment in air dominance by attacking the weak points presented by dependence on nearby airfields. This is a deliberately asymmetric strategy that offsets the fighter-heavy approaches preferred by the USAF and the only remaining carrier-based option for naval aviation. The Chinese target analysis is easy – if they inhibit the ability of the U.S. to fly aircraft and dock ships, then the U.S. will be effectively neutralized in the western Pacific.

The obvious response to this strategy is for the U.S. to engage in some asymmetry itself, including a number of options which entail fighting from a distance. In the old European model, where NATO and Warsaw Pact air forces squared off over compact territory, speed, survivability and maneuverability were the attributes that largely described the utility of combat aircraft, which reinforced a trend towards fighter aircraft. In the Pacific, with its long distances and island bases, the key attributes are range, sensor capability and payload, which are typically attributes of the bomber. For operations over long distances, the combination of penetrating bomber (LRS-B) and standoff platform (B-52J) could provide a formidable combat capability by the mid-2020s.

Strategic Context

Inside the Pentagon, the focus on fighting China is often handicapped by a focus on widgets, rather than strategies. Against China, this manifests itself as a technology-heavy “offset” construct, where newer is better, technological advantage is everything, and cost is no object. The enemy essentially lies vulnerable to an assault by advanced technology, divorced from terrain, unconcerned with distance, and uninformed by strategy. The reality is that China’s military strength is greatest over its own territory, and is not today technologically disadvantaged enough to allow U.S. airpower free rein over the mainland. However, PRC military power fades rapidly with distance from its shores, and China is currently limited in its ability to project power over distance. More importantly from a strategic standpoint, China is not nearly self-sufficient industrially, and is highly vulnerable to campaigns based on Strategic Interdiction or Offshore Control. Militarily, China is like a grizzly bear with a peg leg – brutally dangerous at close range but unable to travel any distance from home. This is a major strategic vulnerability because China is essentially an island nation, with over 96 percent of its trade (by mass) being transported by sea, with no viable alternatives across any land border.

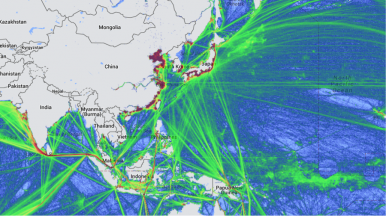

A glance at the chart reveals much. China is geographically constrained in a way the United States is not, by offshore island chains owned by other countries – countries that rarely have cordial relationships with their bigger neighbor. Traffic densities are critically constrained by the Straits of Malacca, and to a lesser extent, passage through the Lombok and Makassar Straits. The Chinese refer to this as the “Malacca Dilemma,” and maintaining that sea-lane is their primary maritime security consideration. But the challenge is not limited to Malacca only –the first and second island chains effectively channel shipping traffic to and from China and provide an immutable strategic advantage for the U.S. A warfighting strategy focused on treating China, like Japan before it, as an island nation allows U.S. airpower to be used from a great distance, avoids the trap of attrition warfare, and allows the U.S. to capitalize on an asymmetric strategy that has no reciprocal path for the Chinese to replicate.

Figure 1: 2014 Maritime Traffic Density (Marinetraffic.com)

The B-52J

Under a distant interdiction strategy, the bomber becomes the premier force, provided that threats to the bomber can be mitigated. Their extremely long range allows bombers to conceivably be based on U.S. or Australian territory and conduct effective operations from a great distance, with basing out of reach of attack from ground-launched ballistic and cruise missiles. The heavy payload means that a bomber can do the work of flights of fighter aircraft, provided that they have the tools required to be effective at a standoff distance from the threat. And the long flight times mean that a bomber aircraft can effectively surveil large areas of ocean, a task made easier by the restrictive maritime terrain in the region. The ideal strike aircraft in this environment is one that has long-range sensors to detect, identify, and support weapons against surface combatants from outside their effective defenses. Against the Soviet threat in the North Atlantic, the Harpoon-armed B-52G fit this bill. In the more crowded Asian littorals, against the Peoples Liberation Army Navy (PLAN), a more advanced set of capabilities is necessary.

The future bomber force could consist of aircraft optimized for two different sets of conditions. LRS-B would be a penetrating aircraft, designed for survival in or around a modern air defense system. The B-52J would assume standoff roles, using longer-range weapons capabilities to strike from a distance. The shaping requirements of the LRS-B will likely preclude the massive wing of the B-52, which allows for large fuel storage, external weapons carriage, and unmatched high altitude performance. Similarly, the B-52 will never again be a penetrating aircraft, lacking as it does the speed and low observability characteristics of the LRS-B.

A modernized B-52 would improve on the airplane’s basic attributes to better meet these standoff requirements. The objectives of a whole-aircraft modernization would be to extend the service life of the aircraft and adjust to the advances made by adversary systems since the initial design. Under the J proposal, the refitted bombers would receive several upgrades:

- A replacement of the ageing TF-33 turbofans with modern, low-maintenance turbofans derived from regional jet designs

- Installation of a modern AESA radar to provide broad area maritime surveillance, ship identification, situational awareness and standoff weapons employment

- Weapons certification upgrade, including JDAM-ER, JASSM-ER, Standard Missile derivatives and antiship weapons

- Certification of NASA’s 25,000-lb. Aerospace Vehicle Pylon as an option in place of Heavy Stores Adapter Beam for Pegasus derivatives.

- Upgrade of communication systems to include Link-16, Iridium, BLOS communications and to provide the baseline for integration into Navy Integrated Fire Control (NIFC).

- Modernization of ESM and EA systems to provide both passive detection and self-projection jamming against the threats capable of addressing a stand-off platform

- Aircraft upgrades, including improved cooling, high-capacity electrical generation, glass cockpit, addition of an APU, removal of excess weight and RVSM compatibility

- Upper Wing Skin replacement (if necessary)

At the end of the conversion, all remaining B-52H could receive the refit, resulting in around 82 B-52J total aircraft inventory.

The Upgrades

Engines. The B-52 has been the subject of at least four major re-engining studies, the most recent having been completed by the Defense Science Board in 2004. In every case, the studies have concluded that replacement of the aged TF-33 turbofans would result in an increase in reliability, lower fuel consumption, and an overall savings, provided that the B-52 remained in service for at least another decade. The USAF has been unwilling to commit to retaining the B-52, but the J model upgrade proposed here would extend aircraft viability to at least 2050, placing the economic argument on solid ground. There are several modern engines in the regional jet class with similar dimensions and thrust ratings to the TF-33, allowing the 8-engine configuration to be retained while improving fuel consumption by at least 20 percent, eliminating the smoke trail, and maintaining the full flight envelope. Key parameters for the refit have yet to be determined – there are competing issues regarding the structural strength of the pylon and the aerodynamic shape of the engine pod. The fan diameter of the B-52H’s 17,000-lb. thrust TF-33 engines is 51.5 inches, which is comparable to the most modern business-class turbofans. Examples include Rolls Royce’s BR725 (52 inches / 17,000 lb.), GE’s Passport 20 (51 inches / 20,000 lb.), or the Pratt & Whitney PW1217G (56 inches / 17,000 lb.); the first two engines being lighter than the TF33. A replacement would give the B-52 an unrefueled range of over 9000 nautical miles, allowing strike missions into the South China Sea to be conducted from Hawaii, New Zealand or bases in the Middle East without tanker support. The typical engine in this class has a time between overhauls of 10,000 flight hours, further reducing sustainment costs.

Radar. Improved sensor capabilities are essential in a maritime strike role. A bomber that can detect and ID enemy surface combatants from outside their weapons range has a decisive advantage, particularly against a fleet with limited or no carrier aviation. In addition, air-to-air capabilities will provide the bomber with a degree of situational awareness, reduce its dependency on airborne early warning, and allow it to effectively participate in Navy Integrated Fire Control (NIFC) networks. A modern Active Electronically Steered Array (AESA) is capable of performing surface search, imaging, air search and target track functions simultaneously, allowing a massive capability upgrade compared to the existing radar. Given that ships cannot hide very effectively on the ocean, the radar is not only the most important target acquisition tool, but the most important survivability measure as well. Existing systems may well fit the bill – the Super Hornet’s AN/APG-79 is already being upgraded with long range surface search and surface target ID modes, although there are other options as well.

Weapons. The weapons upgrade would logically include JASSM and JASSM-ER, adding to the cruise missile capabilities of the aircraft and obviating the need to count on the B-1B, with its very low mission capability rates. Antiship missiles are a key component of the upgrade, be they LRASM, the Joint Strike Missile or improved Harpoon. For antisurface warfare (ASuW) missions, the capability to detect, ID and engage targets outside 150 nm would keep the bomber well outside PLAN antiair weapons range. Use of Quickstrike-ER or Quickstrike-P weapons would allow single-pass aerial mining from standoff ranges, providing a fast-response, offensive mining capability in shallow water.

It is conceivable that air to air missiles might be loaded, giving the bomber a lethal self-defense capability. Indeed, with the large external stores racks, the B-52J could pack a much longer range punch than possible with the medium-range AIM-120 AMRAAM. The USAF modified the RIM-66 SM-1 Standard missile into an air-launched antiradiation missile (ARM) in 1968; conversion of the various long-range Standard missile variants into a long range antiair or antisurface weapon would be reasonable for a bomber aircraft with large external stores capacity.

The Aerospace Test Vehicle Pylon. In 2001, NASA accepted delivery of a B-52H to replace the retiring NB-52B that had served to launch dozens of air vehicles from the X-15 to the Pegasus rocket. Prior to returning the B-52 to the USAF, NASA developed the ATV pylon, which is designed to carry a single vehicle up to 25,000 lb. weight. This would allow the B-52J to carry large air vehicles, including first-generation hypersonic vehicles or orbital systems like the Pegasus, both of which were launched from the NB-52.

Communication Systems. The incorporation of a tactical datalink will be essential for strike coordination, situational awareness and weapons guidance. Link-16 will allow for sharing of tactical data, and the installation of a TTNT terminal will allow full integration with NIFC-CA, the counterair variant of NIFC. NIFC-CA’s architecture would allow for engage on remote, allowing a suitably-equipped B-52J to support antiair shots by fighters and Aegis ships – or the other way around, deepening the missile magazine in any joint engagement. With Iridium NEXT coming on line this year, the installation of an inexpensive Iridium terminal will also enhance the B-52J’s beyond line of sight communications. Combined with the communications upgrade already funded for the B-52H, the complete system will give the B-52J unparalleled communications and datalink capability.

Electronic Warfare. While powerful, the B-52H’s ECM suite is outdated, and is in need of an upgrade similar to that currently ongoing for the F-15C and F-15E. The large airframe of the B-52 has advantages not available to fighters, in that the aircraft is much more amenable to the installation of surveillance equipment that can detect low frequency radars and communications, and the long antenna baselines may allow single-ship target location to occur, particularly against surface targets. This is particularly important in the ASuW role, in that it will enhance the capability to detect and identify hostile surface combatants not using emissions control. In the case of lower frequency voice and data communications, a long-baseline ESM array could detect surface ships by their RF communications links, regardless of any radar or jammer activity. The potential for real-time battle management of Electronic Warfare, run by the B-52’s EWO, would be enabled with the communications upgrade and a new receiver array. A modern expendables system would allow for the employment of smart decoys not currently available to the B-52H.

Subsidiary Systems. The engine upgrade would allow for a full electrical and cooling upgrade to the B-52J, which is likely to be necessary for new sensors and ECM equipment, but which will also significantly improve crew comfort in tropical climates. Since the entire package of upgrades will require the modification of the crew stations anyway, it may be worthwhile to convert the flight deck to a partial or full glass cockpit configuration and make the aircraft RVSM compliant. As with all older aircraft, the B-52H is filled with excess weight from equipment that was deactivated but not removed, including the remnants of the tail gun and fire control system, and this equipment could be removed (and replaced with nonferrous ballast, if necessary), reducing some of the corrosion control issues with the aircraft. Alternatively, the weight and volume could be partially taken up by an auxiliary power unit (APU), which would lessen the B-52’s requirement on ground equipment for external power, engine start and many maintenance functions.

Upper Wing Skin. The final element of the B52J refurbishment is the replacement of the upper wing skin, which is the structural area most prone to failure if the aircraft is flown beyond the 2025 timeframe. At the current flying hour consumption of 250 hours per year, this modification is not necessary, but if airframe flying hours are increased, it becomes an issue. Absent a future structural complication identified by Boeing, this is the key element of airframe refurbishment necessary to take the B-52 well beyond a century of flight.

The B-52J in the Pacific

The refurbishment of the B-52 will allow the Stratofortress to remain dangerous and useful for the next few decades, and is of particular importance to the Pacific Theater. With a modern sensor and weapons capability, the B-52J could be the most lethal antiship capability every possessed by the US. A three-ship of Centuryfortress, required to launch from Darwin, will enter the Sulu Sea and begin patrol three hours after takeoff. With the new engines, the B-52J flight will be able to extend its mission duration to 19 hours with a full load of fuel, surveying 2.3 million square nautical miles during a 12-hour on-station time. (This assumes that the three-ship stays together and that the range of the sensors is 200nm either side of the track. From an altitude of 45,000 ft., the radar horizon extends past 260 nm either side of track, making the possible search area 30 percent larger than calculated.) If the flight encounters an enemy task force, it will be able to lunch as many as 60 antiship missiles in rapid succession – the weapons loadout of two and a half Navy fighter squadrons. Equipped with its own air-to-air radar, the B-52s may operate unescorted outside the range of land-based fighters while still maintaining awareness of air traffic.

Similarly, a flight could carry standoff weapons to a distant launch point, allowing the three-ship to strike targets or emplace a 60-mine field from standoff ranges. With full tanks overhead the field, a B-52 could strike anywhere along the Asian Coast from Taiwan into the Arctic Ocean – taking off from Hickam Field in Hawaii. With this kind of capability, the B-52 fleet will be able to execute long-range, lethal missions from standoff even under conditions where forward fighter bases are neutralized, potentially even supporting penetrating missions by LRS-B. Indeed, an upgraded bomber force could gain strategic effects against China in the absence of basing in the first island chain, allowing effective strikes from a great distance against Chinese power projection capabilities.

Today, the B-1B’s mission capable rate hovers at levels too low to make the aircraft a reliable warfighting platform. The B-2’s sortie rate is extremely low, although the remaining 20 aircraft fill a very special niche. The B-52 is likely to remain the backbone of the bomber force, with its amazingly long range, heavy payload, and the unparalleled flexibility granted by the ability to carry weapons or parasite aircraft externally. The dual-role nature of the aircraft also makes it a critical aspect of the nuclear enterprise, and the necessity for upgrading the bomber leg of the nuclear triad should not be discounted. With a well-considered upgrade plan, the B-52 can serve to its 100th birthday, acting as the backbone for the bomber force until the LRS-B comes on line, and partnering with that aircraft until the middle of the century.

Col. Mike “Starbaby” Pietrucha was an instructor electronic warfare officer in the F-4G Wild Weasel and the F-15E, Strike Eagle, amassing 156 combat missions and took part in 2.5 SAM kills over 10 combat deployments. As an irregular warfare operations officer, Colonel Pietrucha has two additional combat deployments in the company of US Army infantry, combat engineer, and military police units in Iraq and Afghanistan. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Air Force or the U.S. Government.