The announcement that Russia had backed out of financing Kyrgyzstan’s large-scale hydropower projects didn’t necessarily come as a surprise. As both The Diplomat’s Catherine Putz and EurasiaNet’s Chris Rickleton noted, the projects – encompassing both the Upper Naryn cascade and the Kambar-Ata 1 dam – were never especially high on Moscow’s list of priorities. Now that it’s joined the Eurasian Economic Union, Kyrgyzstan remains firmly ensconced within Russia’s orbit, and given the current economic maelstrom Moscow’s dealing with, further infrastructural investments in Kyrgyzstan’s hydropower future lost out to more pressing needs.

Still, it’s clear that Kyrgyzstan’s President Almazbek Atambayev was less than enthusiastic at the news of Russia’s pull-out. While Bishkek has pushed the idea that external investors can still be found, the likelihood of, say, Beijing supplanting Moscow in financing the projects, at least in the immediate future, remains low. As such, Atambayev’s frustrations weren’t necessarily without merit.

Two additional angles within the fallout, however, haven’t seen much coverage but help explain the extent of Atambayev’s frustrations. Firstly, as Jamestown’s Umida Hashimova wrote, Atambayev believed that “Russia may never have planned to actually fund these hydro-electric projects in the first place.” Moscow’s newfound reticence to fund the project, it would seem, only confirmed Atambayev’s suspicions. Not only did Russia’s planned investment, in play since 2012, preclude Kyrgyzstan from finding other investors, but the deals presented one of the primary pillars within the rapprochement between Bishkek and Moscow. Now – with Kyrgyzstan feeling the brunt of Russia’s economic downturn, both in terms of weakened currency and remittance drop-off – that pledge has disintegrated, and proved Atambayev correct. (That said, the question remains as to whether or not it was wise for Atambayev to bottle his concerns before Russia’s final decision.)

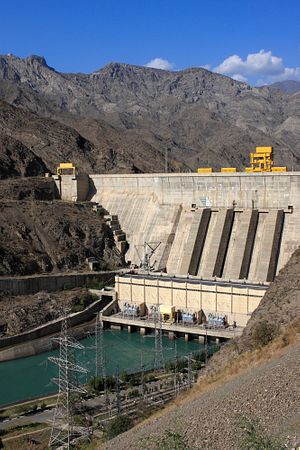

The second detail worth highlighting deals with the Kambara-Ata 1 project moving forward. While Kambara-Ata 1 remains far from finalized, Atambayev reaffirmed that the construction remained necessary, as Hashimova added, for Kyrgyzstan to “meet its obligation to supply electricity to Afghanistan and Pakistan under the CASA-1000 project.” Atambayev’s affirmation undoubtedly perked a few ears in downstream Tashkent, which has railed against Kambar-Ata 1’s completion for years. (Tashkent has also bashed Tajikistan’s planned Rogun Dam, which would exceed Kambar-Ata 1 in scope.) Even though there’s no indication Kambar-Ata 1 remains necessary to the U.S.-backed CASA-1000 electricity project – at least, as it’s currently planned – Kyrgyzstan has nonetheless acted as a net electricity importer recently, effectively negating its role as a planned exporter within the CASA-1000 rubric. More disconcerting, however, is the fact that Uzbekistan’s Islam Karimov has already threatened “wars” should Kyrgyzstan push Kambar-Ata 1 to fruition.

So while Tashkent can breathe a sigh of relief that, for the moment, Kambar-Ata 1 looks far from completion, Atambayev’s continual linkage of the project to CASA-1000 will do nothing to ease regional tensions. Nor, unfortunately for Bishkek, will it be likely to inspire any future investors.