The Diplomat has helpfully published several articles on the neglected topic of how Moscow has sought to use its Far Eastern Federal District, a traditional backwater, as a foundation for building more comprehensive relations between the Russian Federation and the Asia-Pacific region. These pieces (which can be read here, here and here) are well-written, well-researched, and convincingly argue that, along with many other non-Asian countries, Russia has been pursuing a Pacific pivot. However, like many other articles and statements by Russian leaders themselves, they catalog the large number of Russian initiatives and inputs into Asian processes but obscure the small number of positive results and enduring outputs that they have so far achieved. On balance, Moscow is still very far from realizing Russia’s desired place in Asia.

The Russian government has sought to increase Russia’s integration with Asia for both offensive and defensive reasons. These goals include achieving mutually advantageous economic ties in general, developing eastern Siberia in particular, attracting considerably more investment and high technology into Russia, bolstering Moscow’s diplomatic influence on critical Asian issues, raising Russia’s profile in Asian regional organizations, and promoting multipolarity by constraining U.S. influence in Asia without excessively enhancing that of China. Moscow’s main tools to realize this strategy has been to reaffirm Russia’s often overlooked Asian identity, leveraging Russian arms exports and energy riches, adopting a low-key neutral position on Asian territorial disputes except for its own with Japan, and pursuing flexible diplomatic and economic ties with a realpolitik indifference towards countries’ domestic political practices.

Russia has tried not only to tighten ties with China but also to sustain relations with longstanding partners like India, Vietnam, and North Korea, while cultivating new partnerships with Japan, South Korea, and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) to bolster Moscow’s leverage and options. In recent years, Russia has hosted the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Summit and joined the East Asian Summit. Like their peers elsewhere, Russian analysts see demographic, economic, and other trends making the Asia-Pacific the most important economic region in the coming decades. A rising share of Russia’s arms and energy exports are already going to Asian customers.

Russian President Vladimir Putin has led this campaign. In his presidential state-of-the-nation address in early December, Putin confirmed that Sochi would host a Russian-ASEAN summit in 2016. He also proposed studying whether to pursue a massive economic integration project that would encompass the members of ASEAN, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, and the Moscow-led Eurasian Economic Union (EEU).

Poorly Integrated

However, Putin hardly mentioned East Asian issues in his lengthy end-of-year news conference ten days later, reflecting the long-standing pattern of Russian officials announcing admirably grandiose projects to deepen ties that never sustain high-level interest. Russia remains poorly integrated into East Asia’s dynamic economies. The country has some first-rate educational establishments but most Asians who study abroad do so in Europe, the United States, or in other Asian countries. Although Putin can cite record two-way trade figures with some countries, Russia is not a leading economic partner of China, Japan, South Korea, or most other Asian countries. All too often, Russia’s potential contribution is treated as an afterthought in Asian initiatives.

Moscow’s ability to realize its regional goals has been hindered by Russia’s unattractive investment climate, limited use of the country’s abundant human and natural resources, excessive dependence on energy and other natural resource exports, unstable national currency, troubled ties with key regional players including Japan and the United States, and unbalanced relations with others, particularly China. As seen in the recent visit by Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi to Moscow, the foundation of the Russia’s relationship with many Asian states remains arms and energy.

Russians are eager to reduce intra-Korean tensions to transform the Korean Peninsula into a gateway for new Russian economic ties with South Korea and other East Asian countries. Despite several years of intense diplomacy, however, Russia’s economic ties with North Korea are still negligible, while Seoul has lost faith in Moscow’s ability to cajole Pyongyang into abandoning its nuclear weapons program or moderating its provocative foreign policy.

Meanwhile, economic and social ties between Russia and Southeast Asia remain modest. At the aggregate level, the Russian Federation has never ranked among ASEAN’s largest foreign partners in tourism, trade, or investment. Finally, Moscow has been unable to attract significant foreign direct investment (FDI) from any Asian country to the Russian Far East, thwarting Moscow’s plans to use foreign capital and technology to transform the region into Russia’s “window to Asia.” Those few Asian businesses that have made major investments in Russia have largely been focused on the country’s more economically developed European parts.

Despite all efforts to diversify Russian influence by revitalizing its industrial and post-industrial economy and its soft power, and a Kremlin leadership that clearly relishes shock-and-awe diplomacy and has a first-rate diplomatic corps to support it, Russia’s main source of influence remains its arms sales. The Russian economic slowdown that deepened throughout 2014 has further constrained Russia’s socioeconomic ties with Asian countries.

The Russian government has been trying to change this situation for decades. With regards to Southeast Asia, Russia became a formal Dialogue Partner of ASEAN in 1996, but it was not until a decade later that they launched a detailed action program for 2005-2015. Then it took another five years to begin drafting an implementation roadmap, which the relevant government ministers finally adopted in October 2012. Moscow’s current focus is to develop a Russian-ASEAN free trade agreement, but even this achievement would not compensate for the impending incorporation of key members of the bloc in the Chinese-led Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and the U.S.-led Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP).

At a conference at the end of November in Indonesia organized by the Moscow-based Valdai Discussion Club in partnership with the Habibie Center in Jakarta, many of the Asian participants enumerated the serious barriers to closer Russian-ASEAN ties and the difficulties of overcoming them.* For example, they characterized official Russian interest in their region as sporadic, with Russian leaders frequently skipping even high-profile events like the East Asian Summit. On other occasions ASEAN experts have referenced perceptions that Russia is too close to China, too reliant on military power for projecting influence, a business risk due to Western sanctions and domestic problems, and perennially treating Asia as a second choice after having its European aspirations thwarted. They have also faulted Russia’s perceived lack of an overarching vision or strategy for the region, with Moscow’s pursuing unconnected bilateral deals exacerbated by a lack of follow through, and doubts regarding Russia’s long-term commitment to the region once other opportunities beckon.

The Russian analysts at the event offered their own list of obstacles, such as U.S. economic, diplomatic, and security policies allegedly aimed at Russia’s containment, the negative stereotypes of Russia common in the Western media, and their belief that Western sanctions had made Asian businesses fearful of pursuing Russian economic ties. They acknowledged though that the Russian economy is not export oriented and its leading business enterprises are more comfortable dealing with European partners. They hold themselves partly responsible for Asians’ unfamiliarity with the rich economic and educational opportunities available in their country. In Russia, people commonly call Asia ”the Orient” or “the East,” even though Asia lies mostly south of the territory of the Russian Federation, which even after the seizure of Crimea has lost much of its former Soviet territory in Europe. Russian civilian businesses, unlike arms exporters, have generally failed to find their natural niche selling better quality goods than China but at a lower price than Western competitors. Russians further noted that their government had, for logical reasons, focused its recent foreign economic initiatives on joining the World Trade Organization (WTO) and building the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU)

Other impediments hindering Russia from assuming a prominent role in Asia include Moscow’s having the same challenge as Washington in trying to promote multilateral region cooperation between states that dislike their proposed partner. In Moscow’s case, this rivalry includes China vs. Vietnam, China vs. India, and North vs. South Korea. Unlike the United States, which has generally managed to pursue a balanced Atlantic and Pacific orientation for a century, Russia has clearly focused its energies on its westward frontiers. Because of its misbehavior in Europe and its territorial dispute with Japan, Russia still cannot play its potential roles as a Eurasian bridge between Europe and Asia or as a major balancer between China and the rest of Asia. Russian proposals for collective security structures are perceived as too vague to bring concrete benefits and designed to dismantle the U.S.-led alliance structures that have kept regional peace for decades. When the Russian minister attending the May 2015 Shangri-La Dialogue security conference attacked U.S.-sponsored “color revolutions” and regional missile defense plans, his message may have resonated in Beijing but hardly beyond. One reason Moscow is so eager to shake up the Asian security order is that Russia is not a leading member of any strong regional multinational structure.

Some Russian government and NGO participants at the Jakarta meeting warned Asians to avoid joining the TPP because they would have to upend their state-dominated economies to qualify. Moreover, the Russian participants appealed to Asians to distance themselves from the United States by appealing to Asian nationalism, asking aloud “why Asians would want an Asian Century led by a non-Asian power,” as one participant put it. Meeting the high requirements of TPP membership will prove more of a challenge for the region’s statist economies than joining a Moscow-sponsored free trade agreement with the EEU, but the short-term pain would impart long-term development benefits, while security ties with the United States bring advantages, such as ensured freedom of navigation, which Russia cannot guarantee.

Russian leaders have tried to use energy assets as a tool supporting their Asia Pivot. However, many of the deals announced are simply framework agreements or memoranda of understanding that never seem to result in actual projects. Those few projects that have resulted in actual energy flows have often required Russia to make various price and transit concessions. The sad fact for Moscow is that Asian states can play hard to get since they generally possess many alternative sources of energy, now including LNG, shale oil, and other new energy sources. In the future, Russia’s potential leverage as an energy partner could fall even further due to low global energy supplies, globalization of gas markets due to improving production technologies and improved distribution methods, the expansion of energy pipelines from Central Asia into China, the potential for further renewable and energy efficiency gains, efforts within the EU to reduce dependence on Russian energy by developing alternative types and geographic sources of energy, and how Western sanctions are crippling Russia’s Arctic exploration plans.

Perhaps Moscow’s one lifeline would be a comprehensive and balanced Russian-Chinese economic partnership. Russian and Chinese scholars can readily describe such a “win-win” arrangement, which would be based on large-scale Russian energy sales to China complemented by renewed Chinese purchases of industrial and high-technology goods, heavy Chinese company participation in developing the Russian Far East, joint oil and gas resource exploration and production in the Arctic, and integration of the EEU with China’s Silk Road Initiative complemented by other reinforcing mechanisms in line with Putin’s vision.

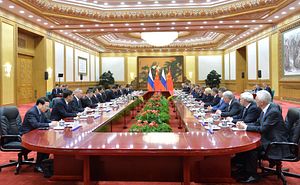

Many Russian and Chinese foreign-policy goals are compatible. They both would like to see more “multipolarity” (read: less U.S. influence) in global affairs while improving bilateral ties, but not at the cost of their flexibility to pursue other partnerships. Their two governments share interests in promoting stability in Central Asia, the Middle East and the Korean Peninsula while deepening mutual trade and investment.

However, though Moscow’s ties with Beijing have never been better, they have never been very good. The bilateral relationship is still mostly marked by harmonious rhetoric but few specific projects outside of Central Asia, arms sales, and intermittent energy deals marked by protracted negotiations over pricing and other disputes. Chinese entrepreneurs have been as wary as others about investing in Russia, with China’s FDI flowing overwhelmingly into other Asian countries as well as the EU and the United States. Despite Moscow’s outreach to Beijing, there is no indication that China has made any effort to use its much greater leverage with ASEAN to assist Russia’s integration efforts

Russia’s lagging presence in Asian economic affairs is not necessarily beneficial to the region. A stronger Russia under a less confrontational leadership could help counter the potential negative repercussions of China’s rise, better rein in a problematic Pyongyang, and more effectively resist transnational threats in Eurasia. Unfortunately, it seems unlikely that Russia will reverse this situation anytime soon.

*Additional information about the conference added.