Franco Galdini is a freelance journalist and analyst. Elyor Nematov is a Getty photographer.

“The trade volume has fallen dramatically. We really feel the crisis biting.” Standing outside his rented container where a variety of men’s clothing is on display, Aleksey’s mood is gloomy. It is a weekday morning and Dordoi Bazaar is a far cry from the trading hustle and bustle of the not-so-distant past.

“The economic crisis in Russia is affecting us all. Fewer people come from Russia and Kazakhstan to buy here, as the ruble and [Kazakh] tenge have collapsed and it isn’t convenient for them any longer,” Aleksey adds.

Porters at Dordoi market Source: Elyor Nematov

Nowadays, it is very common to hear such complaints from traders at Dordoi, a sprawling market of crisscrossing lanes with double-stacked containers serving as both storage and shop, located on the northeastern outskirts of the Kyrgyz capital Bishkek. Once a thriving hub for the re-export of mostly Chinese and Turkish goods on to former Soviet Republics, Dordoi has been experiencing severe difficulties of late in the wake of Russia’s economic downturn, itself the result of plummeting oil prices and Western sanctions linked to the Ukraine conflict, to which the Kremlin has responded with its own set of counter-sanctions.

But Dordoi Bazaar isn’t your average market. A 2012 World Bank report – with data from a series of surveys the authors conducted in 2008 – estimates that it employed about 55,000 people with an annual turnover of around $2.8 billion, 80 percent of which is wholesale trade for resale, mainly abroad. Shuttle trade has long been a Dordoi trademark, as businesspeople and shopkeepers would purchase in bulk and resell the merchandise, mostly in Kazakhstan and Russia, for a profit.

According to the same 2012 report, Dordoi was not only at the center of a network of Central Asian bazaars where re-export was the norm, but it “tower[ed] above them all on all counts.” The significance of such trade for the economy of a small country like Kyrgyzstan cannot be overstated. The World Bank indicates that “the value of [re-export] flows through the bazaar channel averaged 3.5 billion USD in 2007-10, or 77% of the Kyrgyz Republic’s gross domestic product (GDP).”

With no customers, a trader naps inside his container-shop Source: Elyor Nematov

The EEU and Its Discontents

When Russia, Kazakhstan and Belarus created a Customs Union in January 2010, business at Dordoi suffered from the new trade barriers but was kept afloat by high demand in the Russian market and a favorable exchange rate between the ruble and the Kyrgyz som. In August 2015, Kyrgyzstan joined the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU), the Customs Union successor plus Armenia, on the premise that free access to its vast market would “trigger entrepreneurship” and provide “new trade and economic opportunities,” as the country’s then Prime Minister Temir Sariyev explained.

While the government’s line was contested by those who viewed the EEU as an economic Trojan horse to advance Russian President Vladmir Putin’s political ambitions to reassert Russia’s influence in its former Soviet periphery, the lesser-of-two-evils argument won out in the end, as many concluded that the risks of membership were outweighed by those of non-membership. Simplified procedures for the hundreds of thousands of Kyrgyzstani seasonal laborers working in Russia and Kazakhstan also played a major role in the decision to join.

Packaging workers playing cards. There is no work, they say. Source: Elyor Nematov

From its part, the Kremlin created a Russian-Kyrgyz Development Fund with a $1 billion endowment “to overcome the structural changes caused by the new trade regime, to enhance the access to credit for the private sector, and to support the Kyrgyz economy.” Clothing and textiles were included in the list of priority economic sectors and by the end of last year the Fund had disbursed $300 million, with $150 million more expected for 2016.

Almost a year after Kyrgyzstan’s accession, however, not only have these promises of growth failed to materialize, but the EEU common tariff system – based on Russia’s higher tariffs – has translated into a sharp increase in prices for imports coming from non-EEU members such as China and Turkey. “Things have got worse since we joined the EEU,” Rustam tells me. Originally from Tajikistan, he has been trading in Chinese goods at one of Dordoi’s prime central lanes for the past decade. “If before August 2015 I’d pay $2 per kilogram of imported stuff, afterwards tariffs doubled overnight,” he continues.

Bekhtour and Dima confirm that imports from Turkey have suffered from the same protectionist measures, as tariffs for their men’s clothing items shot up almost 100 percent to $5 per kilogram. At the same time, in 2015 the Kyrgyz som lost about 30 percent of its value against the U.S. dollar, further eroding profit margins: “We buy in dollars but we sell in som, so in practice we are spending more for our purchases while our sales at Dordoi are less profitable,” they add almost in unison. The recent appreciation of the som vis-à-vis the dollar has been too slight to alter this dynamic.

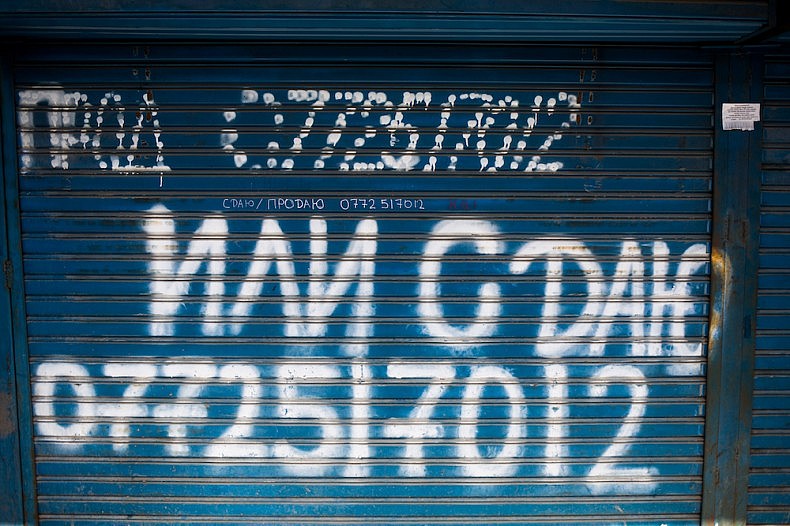

A container up for sale or for rent. At the moment, many containers aren’t used due to lack of trade. Source: Elyor Nematov

The End … or a New Beginning?

At the offices of the Professional Association of Dordoi Entrepreneurs located in the heart of the market, its deputy head Dinara Turbayeva confesses that “as soon as the EEU custom tariffs were introduced, re-export with China basically ground to a halt.” However, she sounds upbeat about the future of Dordoi, “as we are now experiencing a rebirth with the development of our local textile industry.”

What she describes is a veritable change in business model: “If before we were used to having people come to Dordoi and buy someone else’s products – we were basically reselling something made elsewhere, we now need to boost entrepreneurship and compete to sell our own clothes, made in Kyrgyzstan.”

This is a message that the Association has been forcefully promoting as of late, in an effort to counter growing rumors that Dordoi is on the brink of shutting its doors. In two lengthy interviews to local papers in April, Damira Temirbekovna – Turbayeva’s boss – confidently declared that “it is obvious the future of Dordoi lies in the local apparel industry,” adding that the market can “look forward to a bright future as the country’s sewing center.”

A container up for sale. The sign reads: “Urgently selling container at below cost price.” Due to weak trade, many are selling their containers at Dordoi at a loss. Source: Elyor Nematov

To be sure, the “made in Kyrgyzstan” brand has long been known in Central Asia and the former Soviet space for its combination of good quality and competitive prices. An unpublished 2010 USAID study cited by the World Bank “estimates this industry’s output at $1.5 billion, around one-third of Kyrgyz GDP.” But for now, the mood among entrepreneurs at the market fluctuates between caution and resignation.

One entrepreneur, who owns sewing workshops in and around Bishkek and sells the finished product at Dordoi, confirms that trade has halved in the last year, and so have her profits and the number of people working for her. However, she believes that the current crisis is indeed pushing entrepreneurs to innovate and modernize. “Those who kept doing the same stuff have had to close shop, as fashion trends change fast and you need to adapt faster,” she says, adding: “buyers nowadays want more quality at even cheaper prices, so you have to compete to build your clientele.” She concedes though that creating a vibrant and competitive industry will take a long time, particularly because “more capital is needed, as well as training to improve workers’ skills, and the state isn’t helping.”

Others aren’t convinced, especially given the pervasive fall in demand from Russia. “Once we would sell up to a 100 pieces of clothing per day. Now we consider ourselves lucky if we sell 5 or 6,” three middle-aged businesswomen specializing in women’s wear tell me, as we chat under a big sign reading “Made in Kyrgyzstan.” “Buyers are simply not coming,” they add. “Can’t you see how many containers are closed or on sale? Our neighbor sold his for $1,500 a week ago. That’s about a tenth of its price a few years back!

During the market’s heyday, containers in the central lanes at Dordoi were valued at up to $40-50,000 and it wasn’t uncommon to find ads in local papers offering to exchange one for an apartment in Bishkek. As more and more owners are putting their containers up for sale due to the lack of trade, prices have come crashing down. An acquaintance has been trying to sell his in a prime spot for $6,000, with no success. The crisis is so acute that most owners of containers at the market’s edges have stopped asking for rent altogether.

Open for Business?

The three businesswomen point out that, apart from an increase in the price of fabrics and accessories following EEU accession, they have seen little benefits at the Kyrgyz-Kazakh border in terms of the free circulation of goods. The Kazakh government, they claim, is trying to protect its domestic market to weather its own acute economic crisis.

While such claims are difficult to independently verify, Kazakhstan did rush in new rules for the import of cars from Kyrgyzstan only a month before the latter joined the EEU, leaving people to wonder about the actual meaning of “free trade” within the bloc.

“We all thought that the economic union would usher in a common market, with no tariffs for imports between the member states, but we were wrong,” says Alek, an independent entrepreneur who used to import cars from Germany. He was among many who, ahead of EEU accession, imported cars in bulk from Europe and Japan predicting that they could then be sold for a handsome profit to Kyrgyzstan’s richer northern neighbors.

Due to the new measures, however, he now has to sell at a loss in the domestic market: “Cars worth $30,000 are being given away for 20,000 or less. If you are lucky enough to sell, that is,” he laments. “The EEU for us has meant a 300 percent increase in import tariffs for vehicles. We should protect our own small market, like Russia and Kazakhstan do.”

Dordoi market. Made in Kyrgyzstan. Source: Elyor Nematov

An Uncertain Future

Some who lost their job at Dordoi and in the car market left to fill the ranks of Kyrgyzstani labor migrants in Russia, whose remittances have for years contributed up to 30 percent of the country’s GDP. But with Russia still in the throes of recession, the knock-on effects for Kyrgyzstan’s economy are pervasive. Due to the weak ruble, “remittances fell from approximately $2.06 billion in 2014 to some $1.38 billion in 2015,” and the downward trend is set to last for the foreseeable future.

At the beginning of the year, Inter RAO and RusHydro – two Russian state-owned corporations – backtracked on a promised cumulative investment of approximately $3.8 billion to build five hydropower plants in the country due to lack of funds. The Ministry of Economy recently reported that in the first quarter of 2016 overall foreign investments dropped by 16.2 percent compared to the same period the previous year, signaling that earlier statements by the Eurasian Economic Commission – the EEU executive – about investments in post-accession Kyrgyzstan having “more than doubled” may have been overblown.

As for Dordoi, while predictions of imminent closure are probably exaggerated for the foreseeable future, it would be similarly naive to expect the market to continue operating along the same business model that proved so successful in the past. At the same time, it is too early to ascertain whether the current crisis will spawn an innovative textile industry taking the “made in Kyrgyzstan brand” to new levels of quality and profitability with Dordoi market at its center, as the Association contends. For the time being, the empty lanes and closed containers at its edges seem to indicate that Dordoi will be downsizing in line with its declining volume of trade.

Back at one of its central lanes, Rustam appears resigned. “People simply don’t have money, so they don’t buy,” he remarks. “This year I won’t go to China to stock up, as I first need to sell what I have. What else can we do? We need to keep the faith” he says with a brittle smile.