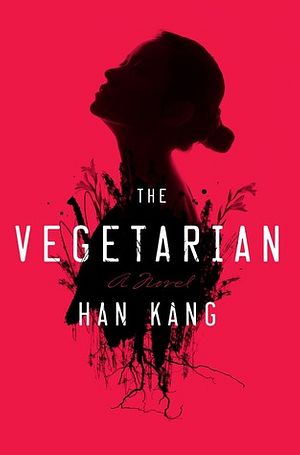

The information on the front cover of my copy of The Vegetarian says that the book had been “shortlisted for the Man Booker International Prize.” This is now outdated. In May, Han Kang’s work has become the first originally Korean-language novel to claim the literary award.

Why read it? First of all, for its language. The book reads more like a poem. The story, though originally consisting of three “separate novelettes,” is really one and can be summed up in a few sentences. A Korean woman by the name of Kim Yeong-hye ceases to partake of meat and most of the action unfolds around this single event. But what matters is how this story is told, and this is through sad, powerful images. Han Kang’s style, usually soft and delicate, sometimes suddenly stuns you with a straightforward phrase or a colorful metaphor. “The trees by the side of the road are blazing, green fire undulating like rippling flanks of a massive animal, wild and savage” – says the last paragraph. I have read the English version (the novel originally came out in Korean in 2007) and Deborah’s Smith translation of Han Kang’ style is commendable. Interestingly, according to the media, it took Smith only three years to master Korean before wrestling with this novel and The Vegetarian is also Smith’s translating debut. The other two translations she has done – according to the edition that I have – are Human Acts (also by Han Kang) and The Essayist’s Desk by Bae Suah. Thus, The Vegetarian scored two firsts in one match: It is not only the first novel to be written in Korean to obtain the Booker price but also the first book to hold this award that was translated by a debuting translator.

Second, the novel should be read for its take on the Korean society. To be sure, its message can also be extended to many other societies. (Moreover, thanks to the choice of the subject, the novel ironically offers a healthy review of some of the main Korean dishes.) When the protagonist refuses to eat meat following a dream, her husband is worried: Who will cook meat for him now? (The idea that he could do it himself does not cross his mind.) No matter, his wife explains, as the husband would typically have two of his meals outside anyway and return only for a late dinner. And then there is Yeong-hye’s sister, In-hye, whose husband is at first idle and then, after starting his art work, hardly ever comes home. “Is there a dad in our family?” asks his son, Ji-woo. The main protagonists of this story are all deeply lonely, cast away into a world of workaholism and deteriorating interpersonal relations. Yeong-hye’s choice of abandoning meat is also the abandoning of society.

The book is not a vegetarian’s manifesto. The third reason to read it is that it really digs deep into the reasons for Yeong-hye’s decision, through the layers of the human mind and memory to reveal the true subject of the story: violence. The cruel violence of humans against animals, the silent violence of men against women, the physical domination of parents over their offspring. Yeong-hye “had merely absorbed all her suffering inside her, deep into the marrow of her bones.” And this violence, the novel seems to suggest, is a haunting and yet inescapable part of our life and mentality. Hence, the novel’s hero not only strives to abstain from meat but eventually to become a plant, wanting her hands to “delve down into the earth” and the flowers to bloom from her crotch. Although this is surely a misinterpretation, while reading the novel I thought of the Jain ritual of sallekhana. The similarity I find is the reasoning that the final and logical outcome of radically trying to restrict oneself from hurting others is to abandon this form of life altogether.