Souk (not her real name) was forced to marry a Khmer Rouge member she had never seen before in a quick mass ceremony that lasted less than five minutes. After the ceremony, the woman was urged to enter a room to have sex with him; when she refused, she was raped after being threatened at gunpoint by an officer who insisted she consummate her marriage.

“He said that if he raped me and I shouted, then I would be shot dead,” she declared before the magistrates of the court that judges the crimes committed by the leaders of Khmer Rouge in Cambodia between 1975 and 1979.

Souk had to see her husband every 10 or 15 days under the supervision of soldiers who tried to make sure that they had marital relations. “After that warning, after that rape, that I had to shut my mouth and had to agree to live with my newlywed husband,” she said. Souk gave birth at the end of 1978.

The Extraordinary Chambers of the Cambodian Courts (ECCC), jointly set up by the Cambodian government and the United Nations to hear cases related to the Khmer Rouge’s rule, has focused its attention on the forced marriages and rapes within marriages since August 22. The hearings finished by mid-October and a trial judgement is expected in late 2017. But Souk is also a victim of forced pregnancies, an atrocity that is not going to be investigated as a separate crime but as one related to forced marriages.

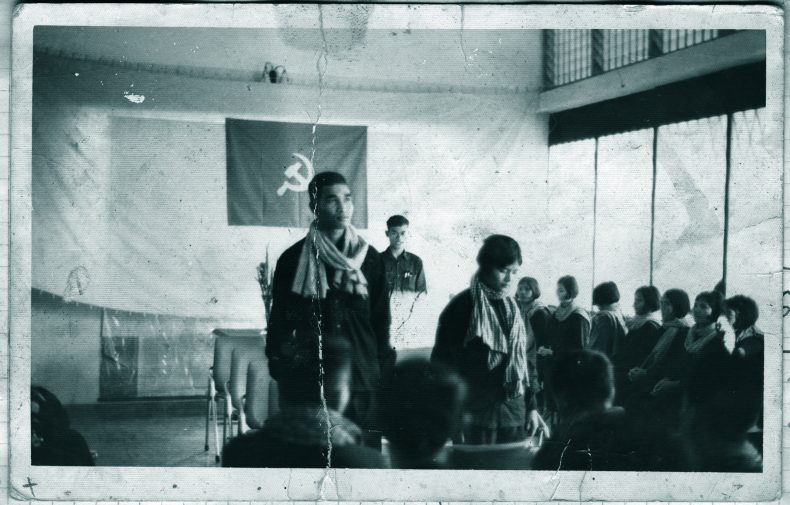

One of the mass weddings held in Cambodia. Photo from the archives of the Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam)

The ECCC court is the only legal mechanism that can judge the crimes committed by communist regime in the 1970s, including gender crimes. Many of the leaders of the Khmer Rouge, now octogenarians, are dying without being tried. Top leader Pol Pot died in 1998 without being held accountable.

When the Khmer Rouge took power in 1975, they completely evacuated the cities and abolished religious practice, private property, money, and the judicial system. Families were divided up by age and gender and sent to labor camps, where they had to work from dawn to dusk to meet the inordinate production quotas. At least 1.7 million people – a quarter of the population — are estimated to have died of hunger, disease, or execution in political purges.

Statements made so far by the court and organizations working with the survivors point out that in this context hundreds of men and women, who had never seen each other before, were forced to marry and spend the night together to consummate their marriage. As a result of these forced unions, which were carried out in practically all the towns of the country, an alarming number of forced marriages resulted in pregnancies, but the concrete number is unknown.

“Any estimated number would not be possible and there is no way to measure the feeling of pain [experience by] the women who have been abused by the authorities. This issue is deeply rooted in Khmer culture and not many women would be willing to share her personal life story, which is still perceived by the society as shameful,” says Youk Chhang, director of the Documentation Center Of Cambodia (DC-Cam), which has collected more than one million reports related to the Khmer Rouge regime.

Prosecutors and lawyers for civil parties contend that forced marriages were designed in part to ensure that the population would double to 20 million people within a decade to get labor power for the regime and the revolutionary ranks. In this way, they could counteract the millions of deaths that began in 1969 with the U.S. bombing of Cambodia in the context of the Vietnam War and the bloody civil war that took place between 1970 and 1975.

Defense lawyers for Khmer Rouge leaders Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan, who already received life sentences in 2014 after being found guilty of crimes against humanity, and whose sentences were ratified on the November 23, however, argue that the regime sought to increase the population not through forced marriage, but by improving living conditions.

For Theresa de Langis, a human rights specialist for women in conflict and post-conflict based in Cambodia, to say that it is too late to take up the charges, or that there is no evidence of forced impregnation as part of the policy of forced marriages in the case filed, “is an outrage.”

“At least one small study of victims of forced marriages indicates that over half of these marriages resulted in one or more children, and testimony has already been heard as to the severe impacts on women’s health and psyche as a result of this added, almost unimaginable burden in a time of mass starvation, slave labor, and epidemic levels of illness,” she says.

A young Cambodian woman in one of the working cooperatives. Photo by Gunnar Bergström from the archives of the Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam)

The report to which de Langis refers, published by the Cambodian Psychosocial Transnational Association (TPO) in 2015, the only organization dealing with mental problems in the country, states that women in particular continue to suffer from the violence they experienced during that time. Some live with the consequences of forced pregnancy or abortion. Others suffer from gynecological and other physical health issues, such as headaches, pain, and disability. Most have ongoing psychological issues related to trauma.

De Langis says the court has been unwilling “to hear the full scope of the gender crimes that occurred.”

“Defenders from the beginning have had to press for the inclusion of these crimes. As a result, forced marriage and rape within such marriages have been heard in Case 002/2,” she explains.

Argentine lawyer and researcher María Lobato, who worked on issues of gender violence in Cambodia and wrote a comprehensive report on forced pregnancies published in March 2016, explains that judging forced pregnancies as a separate crime related to marriages is “completely possible” under the court’s internal rules, but the trial “could be more controversial.”

Forced pregnancies were recognized as crimes against humanity for the first time in the Rome Statute of the International Court of 1998, long after the fall of the Khmer Rouge regime of the 1970s. But the law also has a clause that allows “those acts not specifically determined in the law and that can be considered as inhuman acts” to be officially judged crimes against humanity. The court is currently that clause to judge deportations, enforced disappearances, arbitrary detentions, or even forced marriage, says Lobato.

The lawyer believes that each of these crimes requires a different and concurrent analysis, but the forced pregnancies seem to have disappeared from the attention of both civil parties and judges. According to Lobato, “Forced pregnancies have been completely invisible, characterizing the reproductive function of women as an inevitable consequence of marriages.” No hybrid or international court has pursued this type of crime to date, states Lobato in her report.

Ana Salvá is a freelance journalist based in Southeast Asia.