Emotions in certain parts of Tamil Nadu are running high after the Supreme Court’s ban on Jallikattu, a bull-taming sport, which is celebrated mostly by farmers during the Tamil harvest festival of Pongal.

Thousands of students and pro-Jallikattu supporters have thronged the streets of Chennai, and in 72 other districts of Tamil Nadu, protesting against the Supreme Court’s ban, as they feel that the ban amounts to an assault on Tamil tradition and culture. The impromptu nature and the magnitude of the protests have taken the state administration by surprise, and if continued the protests may lead to a serious law and order problem.

All political parties, cutting across their differences, have joined hands to call for the lifting of the ban in deference to the wishes of the people. Why, they argue, ban a sport that has been celebrated from the Sangam period (100-400 BCE), and has become a part of Tamil culture and tradition?

In fact, the state’s main opposition party, DMK, has laid the blame squarely on the ruling AIDMK government for not pressuring the center to issue an ordinance to allow the event, at least during the Pongal festival.

The state government finds itself in a bind, as it can only lift the ban at the risk of inviting contempt of court proceedings from India’s highest court. The chief minister of Tamil Nadu has approached the central government to issue an ordinance for allowing the sport. The central government, although sympathetic to the sentiments of the people of Tamil Nadu, has refrained from issuing such an ordinance, as it would almost certainly be struck down by the Supreme Court.

The controversy started when animal rights activist groups approached the Supreme Court in 2011, asking for a ban on the sport on the grounds of cruelty against animals. The Supreme Court, disposing the petitions of the animal activists, banned the practice in a judgment delivered in May 2014. The pro-Jallikattu supporters raised a fundamental question: whether the courts should adjudicate on matters relating to centuries-old tradition. The Supreme Court answered that it can, especially when the practice involves cruelty against animals.

For the last two years, in deference to the court order, Jallikattu events have not been organized. However, there is a simmering anger against the ban among farmers.

The late chief minister of Tamil Nadu, J. Jaylalithaa, approached the central government about an ordinance to allow Jallikattu during the Pongal festival. The Ministry of Environment, Forests, and Climate Change issued a notification on January 7, 2016, allowing bull-taming under certain conditions. The People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) and other animal activists then approached the apex court to strike down the notification. On January 16, the Supreme Court stuck to its earlier judgment banning the sport.

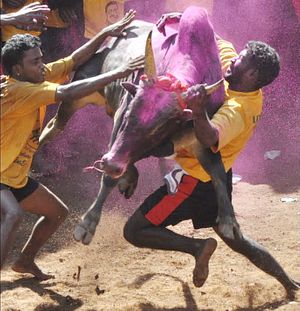

In Jallikattu (the Tamil word for the silver and gold coins tied to the bull), undomesticated bulls are bred for the bull-taming ceremony. Participants are required to embrace the wild bulls and prevent the terrified bull from escaping. In the process, many participants (and many bulls) get seriously injured. Prizes are awarded to those who succeed in taming the bulls. The sport has become so popular that people travel from far-off villages to witness the event.

India has stringent laws on many social issues like dowries, child marriage, and triple talaq, yet these practices persist. No law can change certain practices that are not in sync with modern values, unless the society itself is willing to change.

There are reports that people in Madurai and other parts of Tamil Nadu have decided to stage Jallikattu events irrespective of the court’s decision. As local politicians have openly declared their support for Jallikattu, the hapless police may find it difficult to physically stop such events.

If the court refuses to reconsider its ban, the people may force the issue by organizing Jallikattu events regardless — in which case the only result would be undermining the judgment of the highest court of the land, a situation that should be avoided at all costs.

K.S. Venkatachalam is an independent columnist and political commentator.