For the past two weeks, hundreds of right-wing Islamists belonging to various religious parties have been protesting in Islamabad which has disrupted the capital’s life. The protesters have been demanding the resignation of the federal law minister over a recently omitted reference to the Prophet Muhammad in a constitutional bill. While the law minister has apologized by terming the constitutional amendment a “clerical mistake,” the protesters continue to insist that they will carry on the protest unless the minister resigns.

Last week, the Islamabad High Court (IHC) ordered the federal government to ensure that the protesters leave the capital within a day. However, the protesters have not moved an inch, forcing the federal government to request the court for more time to negotiate with hard-line religious leaders that are leading the sit-in. On Monday, the Supreme Court (SC) of Pakistan took a “suo moto” notice of the situation, asking the government to clarify its position on why the latter has failed to evacuate the capital which remains paralyzed.

So far, the protesters have ignored the government and other institution’s warnings and have vowed to confront the state’s power to protect what they believe is their divine right to guard “the absolute finality of Prophet-hood of Muhammad.”

The government appears to have lost control of the situation with hard-line religious groups challenging the state’s writ by terming the ruling party’s recent controversial constitutional amendment anti-Islamic and blasphemous. The situation in Islamabad points toward an existential challenge for Pakistan which can have catastrophic results for the country if the state’s policy of giving in to hard-line Islamists inflaming religious passions is not dealt with.

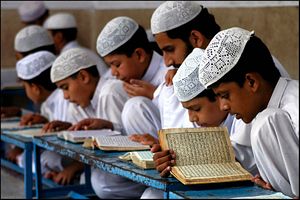

The problem with Islamabad’s sit-in is that it resonates with millions of people across the country that also believes in implementing one particular version of Islam on others with force and violence. The curriculum in public schools still continues to promote hatred against minority Muslim and non-Muslim groups. Students are taught to hate each other because they share different faiths. Christian, Hindus, and Ahmadis and other minority Muslim and non-Muslim communities are presented as lesser humans and a threat to the state’s so-called Islamic identity.

For instance, this is what one state-approved book teaches young minds about the necessary prerequisites for being a true Muslim: “A person who does believe in oneness of Allah, the absolute finality of Prophet-hood of Muhammad (PBUH), the Day of Judgment, and Books of Allah, is a Muslim.” Moreover, the book also states that “religious seminaries [are to be] patronized and annual financial assistance should be given to them.” “The Muslims were weakened during the British empire. On the other hand, the Hindus, Sikhs and Christians enjoyed complete cultural and social liberties. To be a Muslim was a crime at that time,” notes the Punjab Textbook Board’s Pakistan history book.

By defining parameters of who can and cannot be a true Muslim, the state is only sanctioning and legitimizing violence against religious groups that may share different faiths. Such narratives in curriculum and society only strengthen hard-line religious groups’ narratives of implementing one or some sects of Islam with force even if that means taking on the state itself.

The country’s National Action Plan (NAP) against terrorism which was devised three years ago to deal with such challenges comprehensively has failed to deal with core issues that are radicalizing and militarizing Pakistan’s society. While the NAP says that religious seminaries will be regulated with complete checks on their funding resources, the state’s curriculum states that religious seminaries should be patronized and offered funding.

Arguably, the protesters in Islamabad are a product of this curriculum. They are refusing to obey the state’s orders because the social, cultural, political and ideological environment created by the state over the last three decades only allows space for a radicalized society. They are citing divine rights to wage a holy struggle against some of the groups that do not share their religious views because that’s what the state has been taught them.

While NAP and other counterterrorism plans discuss de-radicalization of militant groups, the state is not focused on de-radicalizing itself by rejecting ideas, narratives and traditions which are engendering the radicalization of society in the first place. What is further alarming is that there appears to be no effort to contain the narratives of fundamentalist forces in Pakistan. In fact, the state has reached a point where such radical groups reflect the influence of a state within a state.