Since the 1980s, the American corporate income tax rate has remained unchanged, all while OECD countries consistently started to reduce their own. With lower rates soon to be signed into law, a key economic policy objective of Trump is taking shape: to make the United States more competitive.

The tax overhaul is unlikely to significantly affect the Chinese economy, nor will it pressure China to reform its tax system as a response. In this interview, Alicia Garcia-Herrero, chief economist for the Asia-Pacific at Natixis and senior research fellow for Bruegel, analyses what U.S. tax reform means for China.

Maurits Elen: How will Trump’s tax bill affect China?

Alicia Garcia-Herrero: The most concerning issue for China is whether Chinese enterprises will flee to the U.S. for lower tax preferences. This may be the case for a few number of firms, but is not likely to be widespread. We believe the general impact is at most moderate due to the following reasons.

First and most important, the tax rate is never the only issue bothering enterprises. Industry chains, labor skills, infrastructure, closeness to market, and so on, are all at play for an entrepreneur’s choice of investment location. In fact, China has already integrated taxes by removing most preferential taxes after 2007, but there has been no drastic outflow of foreign capital. For the existing investment in China, the sunk cost associated with these investments will also prevent investors to retreat to the U.S.

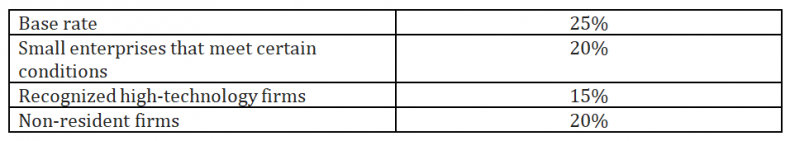

Second, even considering corporate tax itself, the U.S. has little absolute advantage against China, especially for high-technology firms. The current baseline corporate income tax is 25 percent in China, but Chart 1 [below] shows that, for small enterprises that meet certain conditions, high-technology firms and foreign enterprises, the corporate rate can even be as low as 20 percent or 15 percent. In fact, only a very small proportion of Chinese firms need to pay the full 25 percent to the government. As such, a lower U.S. corporate tax rate of 20 percent is still not advantageous over that in China.

Chart 1: China’s corporate income taxes.

Admittedly, because of the low implementation in collecting taxes, China’s current tax system has a very high reliance on value added tax (more than 30 percent), which is not existing at all in the States. However, one also needs to consider that personal income tax is very small, which contributes to only 6 percent of China’s total tax revenue, so the net effect may not be so burdensome for Chinese enterprises.

Last but not least, most Chinese local governments still give implicit subsidies to large investors to compensate for their losses in tax. This is key for local government to keep these investments in their region, a phenomenon known as “local tax competition.” These subsidies are very flexible. Therefore, even if the U.S. tax reform has any potential to affect Chinese investors, the local government can easily increase their subsidies to buffer the negative effect.

How do you expect China to respond?

As stated, U.S. tax reform has only moderate impact in China, so there is no strong incentive for Chinese policy makers to adjust their tax policy. In fact, China’s fiscal deficit has already deteriorated to 3.7 percent in 2016 and will certainly be under higher pressure in the next year due to all the pending welfare programs, including the enhancement of social security funds. Although China still has a lower government debt ratio compared to the U.S., it is not likely to tolerate a very high deficit, as it could drag down investor confidence in the economy. Hence, the room for further tax reduction is limited.

However, it is very likely that the government will announce some measures to give confidence to local investors. We think the most likely breakthrough is to also lower corporate taxes to, say 22 percent or 20 percent, to show the government’s resolve to support investment. Nevertheless, this will not change the current tax scheme too much.

Should China reform its tax system?

There is strong incentive for China to reform its tax system, but more from its own perspective instead of U.S. pressure. China’s tax structure is very unreasonable for two reasons.

First, the contribution from direct taxes, especially personal income tax, is particularly low. Despite a heavy load design, which can reach up to 45 percent, only 30 million people pay personal income tax, according to Jia Kang, head of the Research Institute for Fiscal Science affiliated with the Ministry of Finance. This type of tax system has little distributive effect.

Second, tax subsidies are so widespread that a firm’s real payment to the government is in most cases associated with its bargaining ability with the local government. In this sense, the tax system has become part of China’s industrial policy to support certain firms, which only worsens the misallocation of efficiency.

We believe China needs to reform its tax system to improve its efficiency with more transparency, but this may not be fully interpreted as a response to U.S. tax reform. Moreover, we see reform is difficult to implement in the short run, as it will require to revamp the whole system.

If China lowers taxes, how do you expect this to be balanced in the budget, especially now the government wants to focus fiscal policy more around social spending?

We do not think China can balance its fiscal condition, even without a corresponding tax reduction due to U.S. pressure. After all, increased social welfare spending is indeed inevitable. Furthermore, the government eventually needs to bail out some central SOEs [state-owned enterprises], explicitly or implicitly, which will only enlarge an already expanding deficit.

One possible solution to buffer fiscal burden is to tax SOEs that are more profitable. Nowadays, the Chinese government has already required SOEs to submit 10 percent of their profits to help the national social security fund, and we believe this is only a beginning. The implementation of mixed ownership reform, which blends SOEs with POEs [privately owned enterprises], could even involve some large private enterprises to support the government for its debt expansion. These measures will avoid any sudden fiscal crisis, but nonetheless, will only drag down the long-term efficiency of the economy.

China has widely been advised to reduce support to SOEs so that market forces can boost the economy’s productivity. But China seems to embark on an increasingly state-led model, which supports large SOEs. Do you think such a model is counterproductive?

The new era will see a more complicated story than before. In the 19th Party Congress, China highlighted the word “state-owned capital” in lieu of “state-owned enterprises.” It means that the Chinese government will extend its control to not only profitable SOEs, but also POEs. A profitable POE may also be required to assist some non-profitable SOEs. As such, the current state-driven model will become more influential in the economy.

Certainly, this is counterproductive for any economist who believes in the market economy. Government influence will cause an entrepreneur’s business decision to deviate from pure business consideration, which could lower efficiency.

This interview has been edited for clarity.