When Japan resumed commercial whaling two years ago, whalers expected that the nation’s whaling industry would be reignited. But it was not to be.

Japan’s third coastal whaling season opened three months ago, but little has changed. Whale meat is not becoming more popular and profits are not being made. And to arouse interest, some areas have even turned to creating new types of whale meat cuisines, including whale meat-flavored tongue stews and gelato.

Whale dessert sold in Tsukiji, Tokyo.

There have been educational talks (with celebrities as speakers) as well, dedicated “Whale Towns” at food festivals, a new kitchen car serving whale curry, whale meat school lunches, and promotional videos showing students enjoying some “delicious” kujira-katsu – all part of a larger national campaign by pro-whaling groups to make whale meat mainstream.

Yet, few Japanese people eat whale meat. Eighty-nine percent of Japanese respondents to a 2013 International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW) survey said that they had not eaten any in the last year, and a 2017 Iruka & Kujira Action Network report found that 52.5 percent of the Japanese population is indifferent to it disappearing from the market.

So why is the whaling industry putting so much effort into promoting a meat that hardly anyone eats? Pro-whalers are keen on reviving a bygone era of industrial whaling.

“Image of a Whale Hunt at Goto, Hizen Province” by Utagawa Hiroshige II, 1859

How Whaling Began in Japan

Whaling began in the Edo era (1603-1867). It was only ever carried out sporadically when whales approached the shore, using rudimentary tools like nets, lances, and paddle boats. Whale meat was consumed only by wealthy merchants and samurai.

Then came the industrial revolution, and whale became a global fad. Countries around the world wanted whale oil for their machinery, and Japan did not want to be left out. Several whaling companies began popping up around the country, adopting Norwegian harpoons fired from cannons on steam-powered ships, and going as far as the Antarctic Ocean to hunt whales.

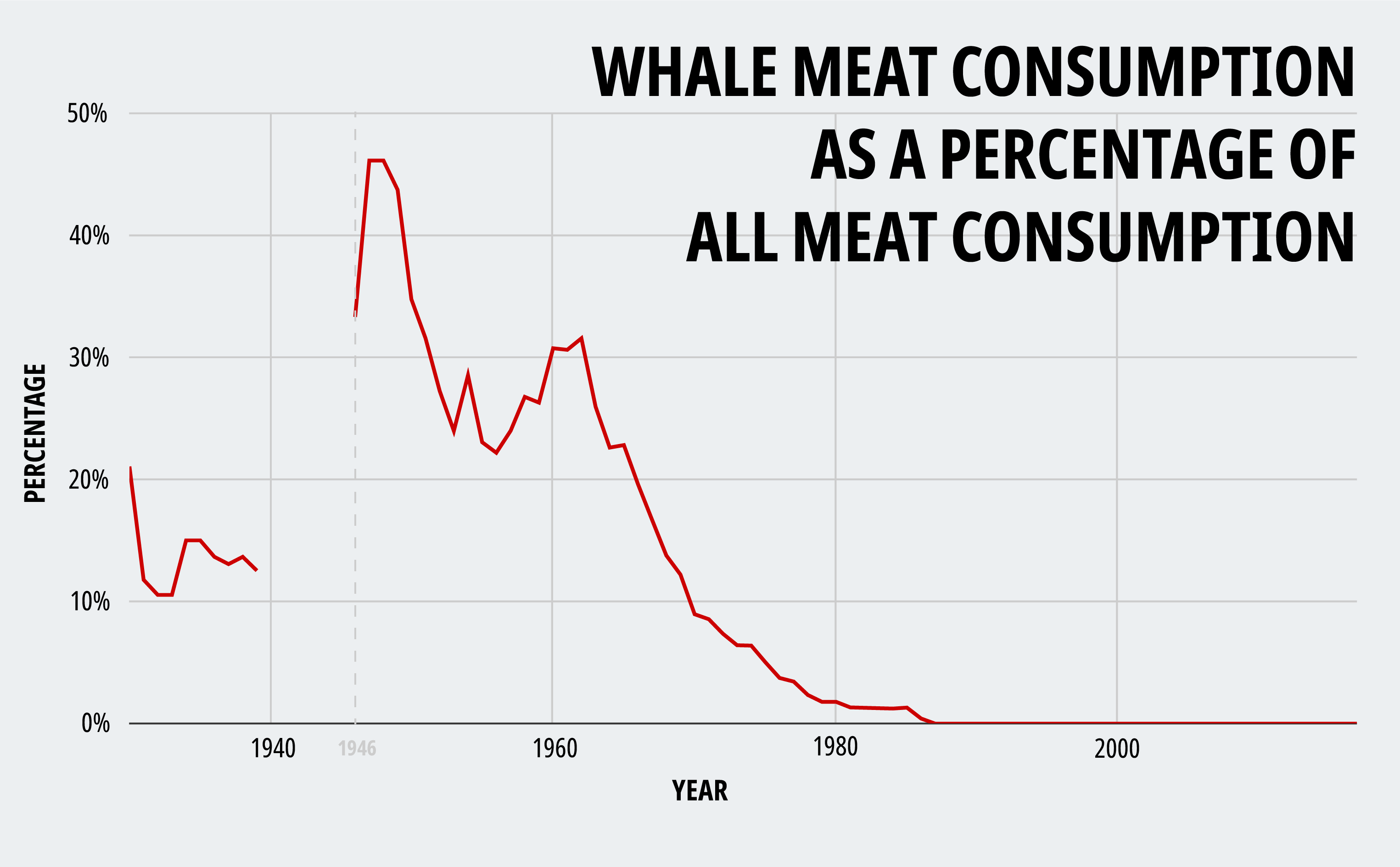

The demand for whales became especially acute after Japan’s World War II surrender, during which U.S. General Douglas MacArthur had to figure out how to address a nation-wide food shortage. His solution was to send a whaling expedition to the Antarctic. The large supply of whale made it the cheapest meat on the market, and within two years, whale meat formed 46 percent of the Japanese diet. Profits rolled into the industry, and along with its global counterparts, Japan brought about a colossal reduction of global whale populations with an estimate of 3 million whales being culled at the peak of the practice.

General MacArthur (left) standing next to Emperor Hirohito (right), 1946

The boom time didn’t last, however. During the 1970s, the Western environmental movement and rising conservation activism compelled governments to do something about the protection of whales. Countries at the International Whaling Commission (IWC), an international body overseeing the conservation of whales and its management, wanted a complete ban on commercial whaling – the very same countries that played no small part in causing the endangerment of whales worldwide.

Japan couldn’t refuse the ban. Not only was it outnumbered at the IWC, but it was also threatened by U.S. sanctions that would have embargoed imports of Japanese fishery products and cut Japanese fishing quotas in U.S. waters. At the height of Japan-U.S. relations with the Ron-Yasu friendship, both U.S President Ronald Reagan and Japanese Prime Minister Nakasone Yasuhiro did not want this to become a thorn in bilateral relations, and so Japan agreed to a moratorium that banned commercial whaling from the 1985/1986 season onward.

The Resilience of the Industry

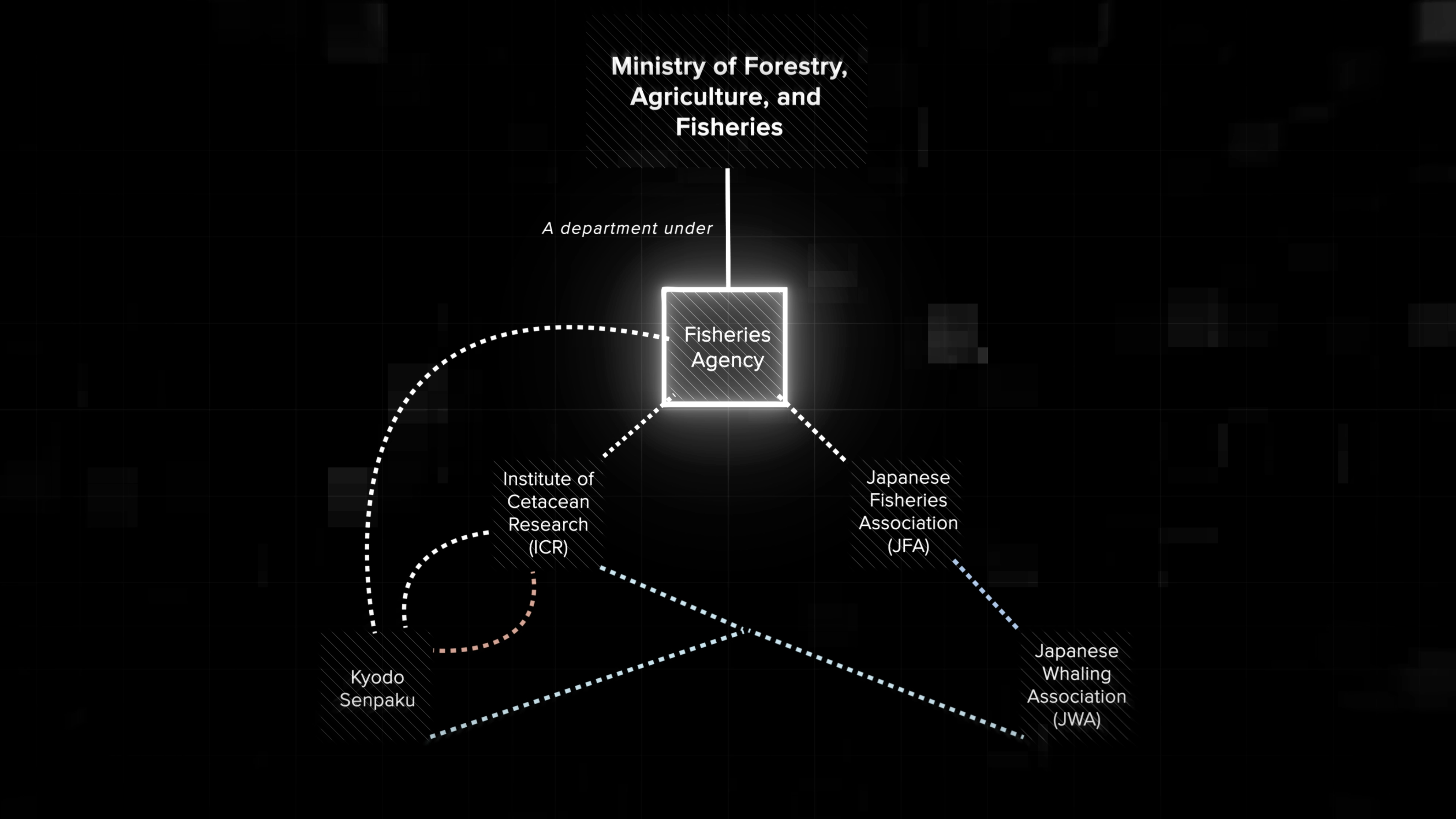

However, Japanese whaling did not end there. It continued its whaling practices in the Antarctic and the Pacific from 1987 onward, just in the form of “scientific whaling” conducted under IWC-approved programs. This bypass was made possible through the Whaling Triangle, a network of pro-whaling groups through which influential pro-whalers exert their influence on government policy.

Whaling Triangle diagram from Anti-anti whaling: Japan’s Resumption of the Hunt

When the whaling ban was enacted, the Japanese Fisheries Association, made up of ex-government officials and lobbyists, asked the government’s Fisheries Agency to fund whaling activities to save the dying industry. It established the Institute of Cetacean Research, which would charter ships from the whaling company Kyodo Senpaku for the purposes of scientific research. Kyodo Senpaku is 100 percent reliant on government help for revenue, and in return, it funds the research institute via whale product sales as “secondary products” of research (and researchers were once caught eating some of it).

The Whaling Triangle helps maintain Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) power bases by protecting the interests of whaling towns. Both pro-whaling LDP “Shadow Shogun” Nikai Toshihiro and Former Prime Minister Abe Shinzo have represented prefectures that house whaling towns for much of their careers, and Nikai is also a member of the LDP Parliamentary League in Support of Whaling. It also ensures that money flows from the government to the industry. Between 1988 and 2013, the government subsidized an estimate of $400 million, and it was also accused of diverting $30 million worth of earthquake recovery funds to finance Antarctic hunts – though the government fiercely denied this.

Nevertheless, Western countries believed Japan was cheating the system (and in fairness its peer-reviewed research output was in the single-digits), and decided to put its scientific whaling programs to the legal test. A 2008 legal case saw Kyodo Senpaku lose its right to whale in the Australian Whale Sanctuary, and a 2014 ruling at the International Court of Justice forced it to terminate its scientific whaling program. In 2018, the program’s coffin was nailed shut when the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) declared it to have illegally traded the meat of the endangered sei whale. After repeated losses, Japan subsequently decided to withdraw from the IWC, marking the start of commercial whaling’s return limited to Japan’s s exclusive economic zone.

A National Cuisine, and Nationalism

After the moratorium was enacted, whale meat consumption hit rock bottom, but it had been decreasing since the early 1960s. Whale meat consumption levels were relatively high in the post-war era because of food shortages, but as the country became wealthier, the public began to shift to other more palatable meats as they became more affordable.

Whale consumption in Japan, 1930-2017. Data from the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries.

Yet, whale meat is still being branded as a national cuisine. Given whaling’s history, it is indisputable that whaling is and has been a local culture in Japan, particular to some regions, but it is highly debatable whether whaling can be considered a “national” culture. Three years have passed since the resumption of commercial whaling, but the industry is still facing a multitude of challenges including cuts in catch quotas and government funding. Kyodo Senpaku even announced that it would try to build its next whaling ship worth $56.4 million by crowdfunding instead of relying on government support, offering additional services such as assisting with marine research, and even ash scattering.

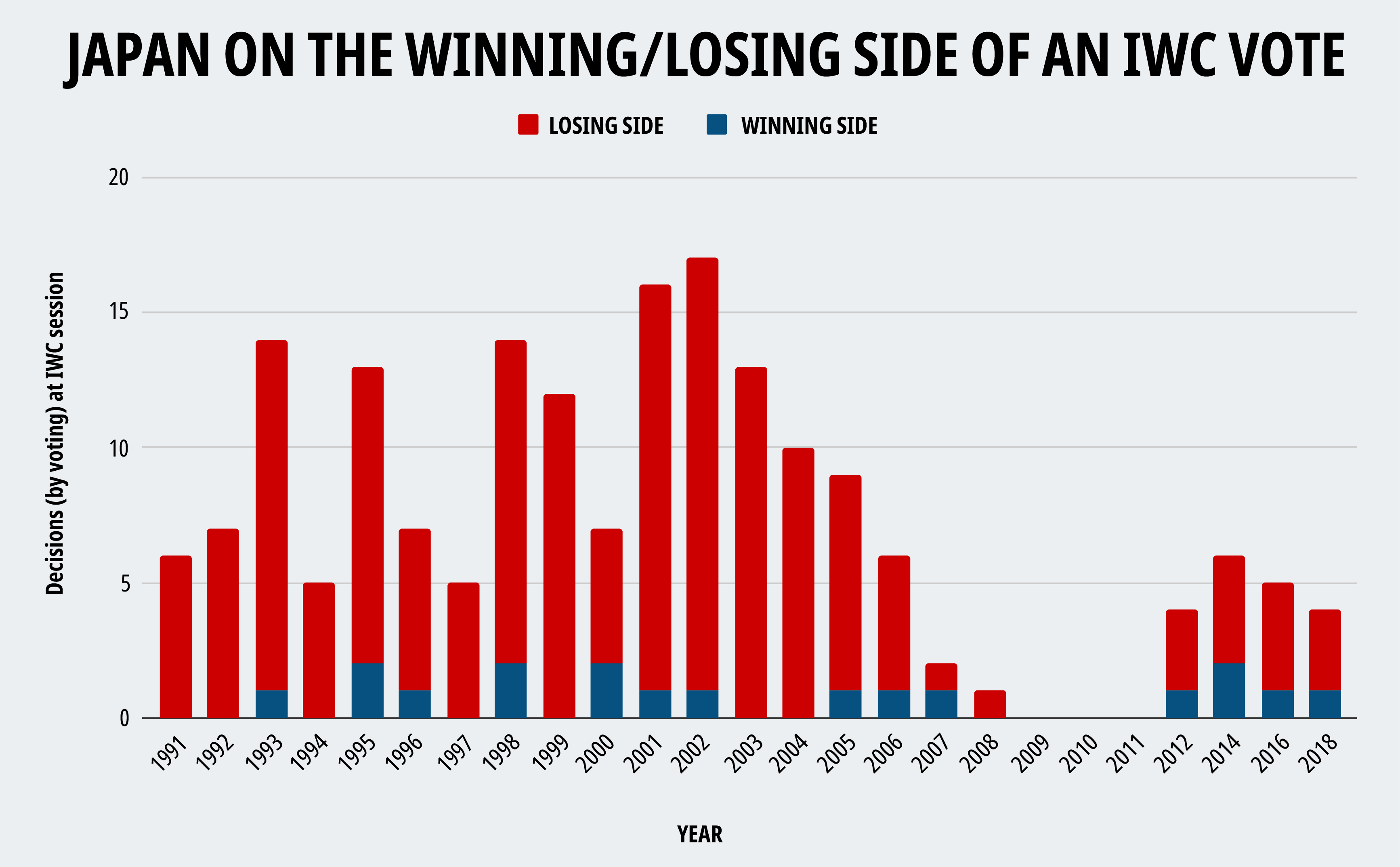

One might ask: How did the industry not foresee these problems? Sadly for Japan, there weren’t many options left. Firstly, it had very few remaining legal avenues to make commercial whaling feasible again. Japan was losing the legal battle in courts, and at the IWC, it was in the opposition 89.7 percent of the time in all decisions made by voting. Its success with changes to whaling regulations was a dismal 0 percent, and the average number of votes that it needed to get its desired outcome became bigger and bigger as years went on – with an average margin of 36.6 percent of the total number of votes. Research has even shown that Japan rewarded countries that voted with it by allotting official development assistance funds, but the voting gap grew so large that it likely became unsustainable.

Times when Japan was on the winning/losing side of a vote, 1991-2018. Data from IWC. (Voting only occurs if a decision cannot be made by consensus.)

The second reason is nationalism. Japan has long desired a foreign policy independent from the interests of other countries, particularly the United States, and its decision to leave the IWC reflects a strong resolve to say “no” to the international community. Pro-whalers remember well that it was the Nakasone cabinet’s capitulation to the United States that ended commercial whaling for good in the 1980s. In fact, Nakasone is the same person that Shintaro Ishihara railed against in his famous book “The Japan That Can Say No,” in which he described the former prime minister as a “villain” for being a “yes-man” to the U.S. government. So while leaving an international organization has damaged its reputation as a player in the international arena, LDP nationalists appear to believe the protest – the act of defiance – to be worth the cost.

It Is Up to the Japanese Public

Unfortunately for anti-whaling activists, the pressure to stop whaling has faltered. Whaling is simply not a salient issue in the mind of the average foreign citizen, and while whaling still pops up occasionally in the public eye, it is nothing more than a tiny blot on the reputation of the nation.

The United States previously threatened sanctions to force Japan to comply with the whaling ban, but that’s unlikely to happen again. Japan’s favorability among U.S. citizens has actually been steadily increasing since 1995. Moreover, commercial whaling is only taking place within Japan’s sovereign territory and is thus perceived as an internal matter, even though whales are migratory and are not bound by borders drawn by man.

Worse still, the aggressive efforts of anti-whaling activists (most often from foreign NGOs) to stop whaling – including harassing whaling ships, throwing acid and smoke bombs at whalers – has wound up fanning the flames of “anti-anti-whaling” sentiment among the public. That is to say, they support whaling simply because they dislike being told by others what they can or cannot do. These activities are construed as evidence of neocolonialist Western beliefs being imposed on the Japanese people, something that nationalists rage about. It has also not helped that the extinction of whales is becoming an increasingly untenable argument as reports have documented strong recoveries of whale populations. Much against their goals, they unwittingly give the Whaling Triangle continued reason to fund whaling activities to seek wider domestic support.

Change can only come from the Japanese public. Only a shift in attitude among the public can topple the pro-whalers’ moral high-ground of branding anti-whaling activities as neocolonialist or “eco-imperialist.” But will the next generation of Japanese people feel differently about whale meat? Given the many problems that still plague the industry, including dismal domestic support and financial troubles, chances are slim – for now.