After passing through an arduous security check and the rescreening of your checked- in luggage, you feel victorious once you exit the Kabul International Airport. The kilometer-long walk from the exit to the parking area gives you time to prepare for the next round of checks and questioning on the street.

The usually bustling parking zone was nearly deserted on Monday, with no porters there to nag you and hardly any passengers to block your passage. Within a few minutes, my friends and I had made it out of the airport area.

A few minutes into the city, the first check post greets you. Afghan security officials, weapons in hand, want to know about you and the contents of the luggage lying in the trunk and the car’s back seat. My driver introduces me as a journalist who is coming from Hindustan (India). Back comes the reply: “Salam brother… kaise ho” (greetings… how are you?). The tall, heavy-built guard asks for my passport, sees my name, and lets us go ahead without checking our baggage.

Indians are generally trusted in Afghanistan and at many places you can manage to avoid a harsh grilling from security by flashing your Indian identity. The next two check posts were also easy going for us.

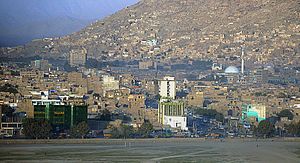

Usually on a normal workday, with traffic overflowing on the street, it takes more than 45 minutes to reach central Kabul from the airport. But today, the streets are almost empty and the journey was completed in around 20 minutes despite breaks at three places for security checks.

I’ve visited Kabul several times in the past, but the feeling this time is different, as if something is really not normal. You can notice this from the way people walk on the street, as if everyone is in a hurry to finish their business and head home.

“The situation here is so unpredictable that anything can happen anytime and anywhere. It’s better you do your work and go home rather than loiter around,” says Habibullah, a shopper at Shar-e-now. This is one of the busiest markets in the city but it has a deserted look these days, with most of the shops shut.

Also starkly visible is the almosttotal absence of foreigners on the street. Gone are the days when foreign envoys or workers used to move about in big SUVs with security guards. Compared to 2009, there are very few foreign journalists or observers covering the poll. Five years ago, the hotel where I am staying used to bubble with foreigners of all hue and cry. Members of the media, mostly TV crews, would be jostling for space to send live feeds. But the hotel presents an eerie silence, reflecting the general mood outside.

The New York Times in a recent report wrote that the Afghan elections, which used to draw “foreigners to Kabul like flies to honey,” are actually driving the foreigners out of the country like never before. The report cites the rising spate of violence over the last few weeks as a reason for this exodus. “Elections used to be a good business for me. In 2009 I earned more than $2000, but this time I am just sitting idle,” says Karim Sharifi, a Kabul-based interpreter.

Safety and security is also a big concerns for locals. Many people in Kabul have left for India or other neighboring countries to escape from the constant tension in their own land. An owner of a popular restaurant told The Diplomat that “[I am] leaving for Canada for two weeks to meet my relatives. My business had gone down in the last one and half months. Some security personnel suggested to me last week to close the shop for safety reasons. I don’t want to risk my life.”

Some of the small guest houses and hotels that usually host foreigners looking for cheap accommodations have been asked to remain closed till further notice.

But the street-side eateries and the bakeries which supply bread (naan) to the city remain very much in business. In the last three decades, the ubiquitous bakeries have seen and survived so many tense moments like these. In central Kabul, when all the shops are closed at 7:30 on Monday evening, the only light that comes out is from the baker’s shop and from a street eatery selling Afghani burgher, a mouth watering spicy dish.

Nazibullah is busy preparing burghers for the few waiting customers. My friend Aamir tells me he is usually very preoccupied in the evening. His shop sells good burghers and customers usually jostle to get his attention. But the 35-year old Nazibullah is more relaxed in the absence of the usual crowd. He even indulges in occasional pleasantries with the customers .

“Ever since I have been born, Afghanistan has been like that. It has not seen a normal life. I can’t think of escaping now. I accept the situation as it is. If you are Afghan, you have to accept such tension as part of your life,” says Nazibullah without betraying any anxiety

But the city at large does betray an anxiety, the likes of which Kabul has not seen since 2001.