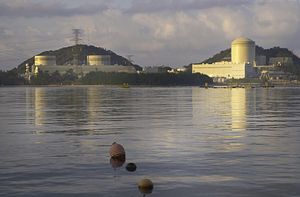

Since Japan instituted what its regulators dubbed the world’s “toughest nuclear safety standards” in early July last year, its Nuclear Regulatory Agency has been reviewing safety screening applications for multiple reactors across the country. On Wednesday the NRA announced its review of Sendai Nuclear Power Plant near the southernmost point of Japan’s four main islands. The inspection officials are expected to approve a restart for the reactors later in the day, although that would not be the final step before they come back online. As this announcement would mark the possible beginning of nuclear restarts under the NRA’s new stringent guidelines, the final steps will be indicative of how the rest of Japan’s reactors are likely to fare on their path to being restarted.

Sendai’s two reactors have been looked at as the first to come back online for quite some time, since last September when the Oi Nuclear Power Plant’s No. 3 and 4 reactors were shut down for maintenance. Since Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s Cabinet approved the new Basic Energy Plan in April, the government has reaffirmed its commitment to nuclear energy as a “base-load electricity source,” a shift from the previous administration’s goal of completely removing Japan’s nuclear dependence by the 2030s. However, “the NRA’s role is to check whether reactors meet safety requirements, not to approve their restart. Actual approvals are the sole responsibility of local government officials,” according to the regulator’s spokesman in an email response to Bloomberg.

Whether Sendai’s operator, Kyushu Electric Power Co., can convince local officials and their public to approve a restart is another matter. The government has instituted a one month consultation period, meaning the plant will have little effect on this summer’s peak usage. One key indicator of the return of Sendai’s reactors may be that the governor of Kagoshima prefecture, Yuichiro Ito, defeated an anti-nuclear opponent in his 2012 reelection.

While these are just two of Japan’s 48 nuclear reactors, they accounted for 5 percent of Japan’s online nuclear capacity the week preceding the 2011 nuclear disaster. The local popular debate that surrounds their restart may offer some insight as to how other local communities will respond when some of Japan’s other reactors finish their safety screenings. Western Japan in particular is stretched to the limit of its energy supply with its nuclear plants off-line, and while no other reactors are likely to come back online this year, places like Fukui prefecture (also in western Japan and with 13 reactors off-line) could become battlegrounds between local populations fearful of nuclear disaster, utility companies that have lost 1.5 trillion yen ($14.8 billion) since the Fukushima Daiichi meltdown, and a government that worries about trade deficits for 23 consecutive months due to the overwhelming increase in fossil fuel imports. The next month will show the extent of public resistance (at least in the southern portion of Kyushu Island), and how effective it can be at shaping Japan’s nuclear policy.