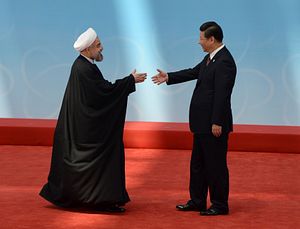

China’s behind-the-scenes support for Iran is what keeps the latter afloat. Despite sanctions that have limited Tehran’s market access, Beijing buys Iranian oil. China advocates on behalf of Iran at the United Nations (UN) Security Council and during nuclear talks with the P5+1 (five permanent members of the UN Security Council and Germany), giving voice to Iranian interests when confronted with Western demands. Iran’s relationship with China may have its points of contention, but the two countries are hardly on a fast track to clash as their policies pivot towards one another.

China has been one of Iran’s most reliable trading partners since U.S. sanctions went into full force in 2010. By maintaining strong ties with Beijing, the Islamic Republic is able to evade Western sanctions and prevent its national currency from falling, two events that could deal crippling blows to the Iranian economy.

Beijing imported 630,000 barrels per day (bpd) of Iranian oil in the first half of 2014 alone, up 48 percent from the previous year. Studies suggest that these statistics are just the tip of the iceberg. With the fourth highest reserves of crude oil in the world, the Islamic Republic is China’s third largest supplier of crude oil, and according to Persian news media, supplies Beijing with 12 percent of its annual supplies.

Clearly, sanctions have never been, nor ever will be, a deterrent to Beijing’s engagement with Tehran in the energy sector. After the U.S. Department of State exempted China from sanctions in exchange for reduced purchases of Iranian crude oil – waivers that were renewed in mid-2014 – the pace of energy deals between Beijing and Tehran has hardly eased.

Oil imports that were supposed to decline under the waivers have increased, due in part to Iranian exports of ultralight oil to China and elsewhere in Asia. Unlike Western allies that tiptoe through the Middle East, making strategic investments only in areas less prone to conflicts or terrorism, Beijing does not hold back on engaging in seemingly tumultuous parts of the globe, so long as its access to energy resources is not interrupted.

But China’s energy quest in Iran also comes at a cost to leadership in Beijing. To a certain extent, the Xi Jinping government has earned a degree of trust with the Obama administration, such that Beijing is included in the recent sanctions waivers. Yet by continuing to import high quotas of ultralight oil from Iran, Beijing both bolsters the Iranian regime and demonstrates its inability to act as a so-called “responsible stakeholder.”

Other than energy, the two countries trade everything from toys to arms. Total trade between Beijing and Tehran has increased dramatically since 2007, when China replaced the European Union as Iran’s largest trading partner. As reported by China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, trade between Tehran and Beijing totaled more than $36 billion in 2012 and according to Iran, non-oil trade reached $13 billion earlier this year.

On a recent visit to Beijing, Iran’s parliament speaker Ali Larijani said that Iran and China are both interested in expanding bilateral ties and that “China finds in Iran a permanent partner for its exports and a source for its growing energy demand.” Iran’s willingness to become a permanent trade partner could not come at a better time for Beijing, as developing a new land and a maritime Silk Road economic belt is a new priority for the Communist Party.

The land-based Silk Road will ultimately traverse through northern Iran en route to Venice where overland trade will link to the maritime Silk road. In combination, the Silk Road economic belt will effectively allow China to reclaim its place as the “Middle Kingdom” by deepening trade and cultural links across three continents.

Potential Chinese assistance in building infrastructure along the land Silk Road will further ensure economic development in Iran – and elsewhere in the Middle East – that is advantageous to China’s domestic economic trajectory.

Another central component of the Tehran-Beijing bilateral relationship pertains to progress in nuclear negotiations. The six-month interim nuclear deal struck between the P5+1 and Iran – signed on November 24, 2013 and recently extended until November 20, 2014 – gives China additional time to sidestep the Western sanctions regime.

The interim deal allowed Iran to recover $4.2 billion in frozen oil funds and export its crude oil (at about 1 million bpd) – and another $2.8 billion in the next four months under the extension – if it took verifiable steps to curb its nuclear program. Tehran has taken steps to eliminate its most sensitive stockpile of enriched uranium, but should future negotiations collapse, the West will have little choice but to reinstate the lifted sanctions and withdraw waivers to China and other Iranian oil recipients.

With a renewed focus on the P5+1 talks, it appears the West is aiming to drive a wedge between the strategic China-Iran partnership. And this strategy seems to be having some success. In April 2014, for instance, Iran abruptly terminated a $2.5 billion petroleum deal with China for work at the Azadegan oil field (near the border with Iraq), estimated to have reserves of 33 to 42 billion barrels of oil. The National Iranian Oil Company declared that China’s National Petroleum Corporation had been “non-compliant” in holding up its end of the deal and had discontinued development on the South Azadegan oil field project. But by June, another big Chinese investor in Iran – China Petroleum & Chemical Corporation, or Sinopec – doubled its production of Iranian oil at the Yadavaran oil field (estimated to have 17 billion barrels of oil) from 25,000 to 50,000 barrels per day.

Speculation that the current interim nuclear deal will allow Tehran to be more assertive with Beijing should not encourage excessive optimism. As recent months have shown, where one deal falls through, the Chinese have promptly found other opportunities to tap back into the Iranian energy network. But it is likely that China and Iran will work to strike a mutually beneficial, but tenuous, balance as the nuclear negotiations move forward.

Both sides have far too much to lose if future talks collapse, or if Iran doesn’t follow through on its commitments. Beijing needs Iranian oil supplies to fuel its domestic growth and uninhibited access to northern Iran for the Silk Road trade route; Tehran needs the energy market, as well as any benefits that can be derived from China’s Silk Road development. Clearly, with these potential losses in mind, this is one deal that neither country can afford to see fall short.

Lauren Dickey is a research associate for U.S. foreign policy at the Council on Foreign Relations and Helia Ighani is a research associate in the Center for Preventive Action at the Council on Foreign Relations.