In April, Kazakh President Nursultan Nazarbayev included an order to generate a plan to switch Kazakh from a Cyrillic to a Latin alphabet by 2025 in a larger “strategic plan,” published in a state-run newspaper. The announcement was a reiteration of a similar call made in December 2012 when Nazarbayev unveiled his Kazakhstan-2050 strategy, including the Latin switch. He’d also suggested the idea in 2006. In 2007, a feasibility study suggested that the switch would take 12-to-15 years and cost about $300 million.

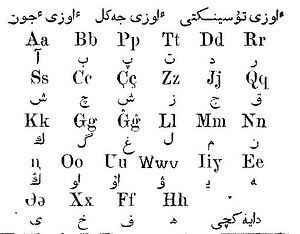

This week Erlan Saghadiev, the minister of education and science, said that the special commission established in April to tackle the issue was working on developing an appropriate Latin-based alphabet for Kazakh. RFE/RL reported that the new alphabet is expected to be unveiled by the end of the year. Starting 2018, the plan is to develop textbooks and get the new alphabet into schools.

There’s a geopolitical angle to this issue which seems obvious: Cyrillic is the alphabet used by the Russian-speaking world and the vestiges of the Soviet Union. Moving Kazakh away from the Cyrillic alphabet, in the worlds of RFE/RL, “appears to be part of efforts to emphasize Kazakh culture while distancing the country from Russia and shedding rules and traditions left over after decades of domination by Moscow.”

The 2007 feasibility study, according to EurasiaNet’s report at the time, included a comment to the same effect:

“Switching the Kazakh alphabet to Latin means for Kazakhs changing the Soviet (colonial) identity, which still largely dominates the national consciousness, to a sovereign (Kazakh) identity,” the report stated. “Among the many arguments in favor of switching the Kazakh alphabet to Latin, boosting the national identity of the Kazakh people is the main and decisive one.”

In recent years Astana has emphasized Kazakhness and the longevity of Kazakh sovereignty — for example, celebrating the 550th anniversary of the Kazakh Khanate in 2015, drawing a direct line from the khanate to the modern Kazakh state.

The alphabet change can be couched in nationalistic terms as a physical manifestation of movement away from the Russian (or Soviet legacy) sphere.

But there’s also the less-sexy angle of simple practicality. Latin scripts are in use in Europe, both North and South America, much of Africa and parts of southeast Asia and Oceania. In comparison to other major writing scripts — Arabic, Cyrillic, Chinese, Nagari — none are as truly global as Latin.

Nazarbayev, in the April article, recounted a brief history of alphabets in Central Asia. From a runic alphabet known as Old Turkic, in use in the the 8th to 10th centuries, to Arabic script, which came with Islam and its armies, Kazakh has been written in many ways. Indeed, Arabic script was used in Kazakhstan until the 1920s but its links to Islam led to a push on the part of secular Soviet authorities to “modernize.” In 1929, the USSR adopted a Latin alphabet, the “Unified Turkic Alphabet” which went into use until 1940 when Cyrillic was adopted across Central Asia.

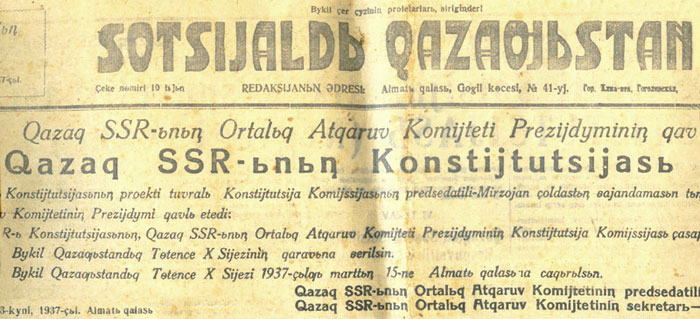

A 1937 edition of the Socialist Kazakhstan newspaper, written in the Latin-based Kazakh alphabet of the day. Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain

Practicality and national pride together make for a compelling argument to make the switch. But that doesn’t mean it will be successful. First, as noted above, Astana has been flirting with this idea for at least a decade and not actually embarked on the switch. Of course, in that time, English-language learning in Kazakhstan has increased, paving the way, perhaps, for a smoother switch if and when it comes. Second, other countries have made this switch and some were successful, such as Turkey, and others, like Uzbekistan, less so. If Astana can study the Turkish case, and learn from the pitfalls of the Uzbek case, it stands a better chance of success.