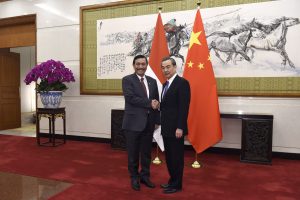

Indonesia’s Luhut Binsar Pandjaitan, serving as the coordinating minister for maritime affairs and investment under President Joko Widodo, traveled to China last weekend ahead of Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s five-country tour of Southeast Asia.

The visit was notable for Beijing’s pledge to boost cooperation with Indonesia in fighting the coronavirus, including backing Indonesia as a hub for vaccine production. “China is willing to work with Indonesia on vaccine research, production and distribution, and support exchanges of relevant departments and medical institutes to help ensure access to affordable vaccines across the region and around the world,” Wang said.

While Chinese coronavirus infections appear to be on the decline, Indonesia’s health ministry reported a new daily high of more than 4,000 new cases on October 9 and nearly 100 deaths, bringing the country’s totals to nearly 345,000 COVID-19 cases and more than 12,000 deaths.

This year marks the 70th anniversary of bilateral relations between Beijing and Jakarta. And yet, 2020 has seen mixed results for China-Indonesia ties. Since January, tensions between Beijing and Jakarta have flared several times over the South China Sea, brought on by Chinese vessels transiting in and along the edges of Indonesia’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ), primarily near the Natuna Islands, where Jakarta’s EEZ overlaps with China’s “nine-dash line” claim. Last month, the Indonesian government issued a formal protest to the Chinese ambassador over a vessel’s intrusion, during which the Indonesian Maritime Security Agency (BAKAMLA) said the Chinese used the term “nine-dash line” in radio exchanges.

Indonesia has firmly responded by dispatching jets and naval vessels amid intrusions by Chinese law enforcement vessels, as well as fishing trawlers. Although tensions have abated slightly since the early 2020 stand off, unambiguous Chinese statements about the waters are likely to color maritime dynamics between the two for the foreseeable future. In January, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Geng Shuang declared, “Whether the Indonesian side accepts it or not, nothing will change the fact that China has rights and interests over the relevant waters.”

Since then, Indonesia has echoed the voices of its neighbors who are formal territorial claimants in the South China Sea. In June, Indonesia submitted a letter to the office of the U.N. Secretary-General opposing the “nine-dash line,” which forms the basis of Chinese historical claims over the South China Sea, stating that the claims lacked an international legal basis. The note also cited the 2016 tribunal award of the Permanent Court of Arbitration, which ruled in favor of the Philippines in the case that Manila brought against China in 2013.

Still, these bubbling maritime tensions are unlikely to spoil the wider bilateral relationship. Given its large population, growing economy and position in Southeast Asia, Indonesia remains important for the success of China’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative. A flagship project is the construction of Indonesia’s first high-speed rail line between Jakarta and Bandung, to be developed by a consortium of Chinese and Indonesian state companies. While China won the contract, outbidding Japanese offers, the project has been saddled with a series of delays due to land acquisition issues and most recently labor challenges amid the ongoing pandemic-induced travel restrictions.

Separately, Indonesia and China announced earlier this month that they are taking steps to promote a framework for local currency exchange and investment settlement between the renminbi and the rupiah. China is a major source of foreign direct investment in Indonesia, second only to Singapore, providing capital for high-profile projects including the development of a lithium-ion battery plant in Sulawesi along with South Korea and Japan.

Moreover, Indonesia’s economy and growth are heavily dependent on the Chinese market. China is the top source for the country’s imports, accounting for 27 percent of Indonesia’s total imports, which amounted to nearly $45 billion in 2019. China is also Indonesia’s number one export market, accounting for 17 percent of its total exports, which reached nearly $28 billion last year. And yet, the promise of economic gain from ties with China may no longer be enough to provide stability in Indonesia and across Southeast Asia.

No matter the importance of China-Indonesia economic and investment relations, 70 years into their formal relationship, the legacy of anti-Chinese sentiment in Indonesia, coupled with simmering tensions over maritime boundaries, are bound to complicate the trajectory of bilateral ties.