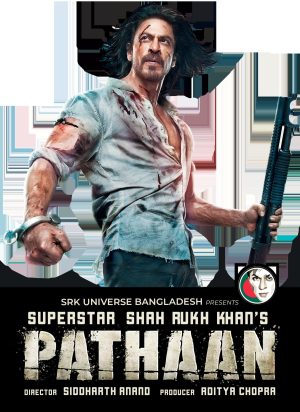

“It was fantastic,” “The king is back,” and “It was so good to see Shah Rukh Khan on the big screen.” These are some of the comments from Bangladeshi Bollywood fans, who were able to watch the Hindi blockbuster film “Pathaan” in a movie theater recently.

Although Hollywood films have been regularly screened in Bangladeshi cineplexes, it has been many decades since Bangladeshis watched Bollywood movies on the big screen.

On May 12, the Bollywood movie “Pathaan” starring Shah Rukh Khan created history when it became the first Indian film to be screened in theaters in Bangladesh in over five decades.

Unlike Hollywood films, which are released only in a handful of cineplexes for the viewing of high-end audiences, “Pathaan” was released in 40 theaters across the country. Audiences included middle and lower-middle-class people.

The decision to allow Bollywood back to Bangladesh was the culmination of lobbying by a consortium of 19 Bangladesh film associations who “decided to allow Hindi-language films to release in the country and suggested that 10 films release a year.”

Bangladesh banned Bollywood films in 1971, when the country attained independence from Pakistan. The decision was a continuation of the ban on Indian films that was in place when Bangladesh was East Pakistan. Pakistani films were also banned in Bangladesh after it gained independence.

It is not that Bangladeshis did not get to watch Bollywood blockbusters in this period. Despite being banned in movie theaters, pirated copies of Bollywood films were available, and Bangladeshis would watch them on VCR cassettes, DVDs, and later, through online and cable channels. Local cable operators through their syndicates kept running pirated copies of Bollywood films.

Actors like Jitendra, Sridevi, and Mithun Chakraborty in the early 1980s, and subsequently, Shahrukh Khan, Madhuri Dixit, Salman Khan, Amir Khan, Deepika Padukone, and Katrina Kaif enjoyed huge popularity in Bangladesh and became household names here.

Similarly, Bollywood songs have been widely popular in Bangladesh and are consumed through local FM radio channels and YouTube.

In a nutshell, Bangladeshis have been consuming and enjoying Bollywood products despite an official ban.

The impact of Bollywood films on Bangladeshi culture is palpable. Dancing to Bollywood music is popular at weddings of upper-middle-class and upper-class families in Dhaka. The entertainment sections of Bangladeshi newspapers regularly publish Bollywood news updates. Traffic in Dhaka grinds to a halt when Salman Khan and Katrina Kaif are in town for concerts.

Even Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, who has been dubbed the iron lady of Asia by the Economist magazine, was present in person to enjoy a performance by Salman Khan and Kaif.

So why did it take so long for a Bollywood film to be released in Bangladesh, despite the widespread consumer appetite for it in the country?

One of the probable answers could be that Bangladeshi film artists and film producers were strongly against the idea of screening Bollywood films in Bangladeshi theaters. They feared that the huge appetite for Bollywood products in Bangladesh would adversely impact the Bangladeshi film industry. Bangladeshi films would lose audiences to Bollywood films. The Bangladeshi film industry would be hit hard, impacting the jobs and livelihood of tens of thousands of people.

Such opposition to Bollywood films was also backed by anti-India sections in Bangladesh. India’s strong support for Hasina’s authoritarian rule, deadly shootings by India’s Border Security Forces of Bangladeshis who cross into India illegally, and India’s unfair sharing of river waters with Bangladesh are some of the reasons for strong anti-India sentiment in the country. It has prompted a large number of young Bangladeshis from across political parties to oppose the expansion of the Indian film business in Bangladesh, although many of them consume these cultural products illegally.

However, for Bangladeshi film exhibitors, screening Bollywood films in Bangladesh makes business sense. The Bangladeshi film industry is not doing well and people in the industry are already losing jobs. Bangladeshi movie theaters are closing down one after another.

As Sudipta Kumar Das, the chief adviser to the Bangladesh Film Exhibitors’ Association, said in an interview recently, “One after another, cinema halls have been shut down due to the impact of ‘obscene’ movies, halls losing audiences, a drought of quality movies and the terrible toll of movie piracy on the business.” Simultaneously annual production of Bangladeshi films has halved. It is estimated to have dropped from over 100 films a couple of decades ago to around 50 films in 2022.

Therefore, to sustain their business Bangladeshi film exhibitors were lobbying the government to lift the ban on Indian films. In 2009, Salman Khan’s film “Wanted” was released in 50 cinemas, but within a week it was pulled out of theaters because of strong protests from Bangladeshi film artists and anti-Indian cultural elites in the country.

The government was forced to back down.

As a result, as Dr. Harisur Rahman argues in his book Consuming “Cultural Hegemony: Bollywood in Bangladesh,” the movie piracy industry and the syndicate of cable TV operators benefitted financially.

The release of “Pathaan” in Bangladesh’s cinema theaters is the outcome of the lobbying of Bangladeshi film exhibitors.

However, not everyone is happy about it. Dhaka-based journalist Iftekhar Mahmud, who is a critic of the government’s decision to allow the return of Bollywood to Bangladesh, argued that the wider release of “Pathaan” is detrimental to the local film industry and to the new generation of Bangladeshi filmmakers who are producing hit films like “Ayanabazi,” “Dhaka Attack,” and “Hawa.”

Dr. Fahmidul Haq, a visiting professor at the Bard College in New York and a well-known film scholar of Bangladeshi origin, however, supports the government’s decision. “I am in favor of the limited release of Indian or any foreign films with some distinct policies that will not damage the local market (but rather may save the declining number of theaters) such as fixing the maximum number of releases, higher taxes on foreign films and limited screen quota,” he said.

Despite the contrasting views on this issue, it is a fact that “Pathaan” has opened up a new income stream for Bangladeshi film exhibitors. The challenge for Bangladeshi policymakers is to now maintain a delicate balance between supporting the country’s film industry, which has been in decline for many years, and expanding support to film exhibitors through regulation to allow Hindi films in Bangladeshi theaters.