| July 9, 2021 | dri.thediplomat.com |

| Asia-Pacific’s Rocky Technology Landscape | ||||||||

|

Welcome to the all-new newsletter of Diplomat Risk Intelligence, the consulting and research division of The Diplomat, your go-to outlet for definitive analyses from and about the Asia-Pacific. Each week, DRI Asia Review will focus on a single country, subregion, or theme, based on in-house research, new DRI products, and regional media monitoring. It has four sections. The Big One offers DRI’s assessment of a major security, geopolitical, or economic issue. Babel is analysis based on translations of articles in regional newspapers and media outlets by a DRI team specializing in major Asian languages. In From Our Stable, you will find analysis based on new DRI products, short excerpts from them, or new multimedia features. And finally, each week Digestif will highlight a concept – from science, technology, economics and even philosophy – that will help you up your analytical game, irrespective of your professional interests. In this week’s edition of DRI Asia Review, we look at how Asia-Pacific powers are seeking to shape the regional tech landscape even as they grapple with key challenges at home. Geopolitics – specifically, a revisionist, rising China’s technology ambitions – looms large over how some in the region approach emerging and established tech efforts. However, others would prefer a more pragmatic approach, refusing to be drawn into sharpening strategic competition between the U.S. (and allies) and China that also, increasingly, has a strong tech component. At the same time, as these quotidian concerns play out from cyberspace to outer space, some scientists are proposing a dramatically different approach to engineering itself, “emergent engineering” as they call it, claiming that existing approaches have failed to deliver when they have been needed most. | ||||||||

Can the Quad Deliver on Emerging Tech Competition? | ||||||||

| Australia's Prime Minister Scott Morrison, left, participates in the inaugural Quad leaders meeting with the President of the United States Joe Biden, the Prime Minister of Japan Yoshihide Suga and the Prime Minister of India Narendra Modi in a virtual meeting in Sydney, Saturday, March 13, 2021. | ||||||||

| — Dean Lewins, Pool via AP | ||||||||

On July 6, White House coordinator for the Indo-Pacific Kurt Campbell reiterated that the U.S. will host the first-ever in-person summit of Quad leaders later this year. This meeting follows a March 12 virtual summit of the leaders of Australia, India, and Japan, and the United States – also a first, and also hosted by the United States. The March 12 summit followed a pronounced increase in diplomatic exchanges among the Quad members, after the group of four was resurrected in 2017 on the sidelines of the ASEAN summit in Manila. While some analysts noted the surprisingly pragmatic tone of the joint statement following the March 12 summit – with a clear accent on softer issues such as meeting the COVID-19 challenge, and climate change – what was particularly exciting for many was the Quad’s commitment to jointly work on emerging technologies. To be sure, signs since last year abound that the Quad was getting serious about challenges as well as opportunities arising from new technologies, such as artificial intelligence, biotech as well as critical supplies needed for them. Australia, in particular, emerged as a leader within the grouping to promote tech cooperation within the Quad. The country’s Foreign Minister Marise Payne announced in December last year that Australia will host the first-ever Indo-Pacific tech summit sometime in the second half of this year. Bilateral Track II initiatives also gave clear indications that the Quad would soon spotlight emerging tech. And then of course is the common consensus among the Quad members that China’s growing muscle in the telecommunications space is an international security challenge. But the March 12 summit commitment gave all these efforts and concerns imprimatur at the highest level. Following the summit, the Quad has committed to establishing a new working group on critical and emerging tech. A White House fact sheet released at the time said, “Quad leaders recognize that a free, open, inclusive, and resilient Indo-Pacific requires that critical and emerging technology is governed and operates according to shared interests and values.” Towards that end, the factsheet noted that the working group would focus on five areas. They include developing common principles on technology design, development and deployment, coordination on tech standards development, telecommunications and supply chain diversification, among others. Of course, whether any of these on-paper commitments will ultimately amount to anything tangible remains to be seen. Multilateral and small groupings often have the unfortunate feature of overpromising and underdelivering, with many ideas floated by them remaining just that: ideas. Pessimists who maintain that, ultimately, national imperatives often derail the best-laid plans for international cooperation would also note that despite the Quad commitment to COVID-19 vaccines for Indo-Pacific (also announced at the March 12 summit), little more than a month later India found itself floundering on vaccine exports as a devastating second wave of the pandemic swept through the country. What was even more damning to some was how, during this time, the U.S. dithered on how to come to India’s aid for more than a week, with prominent Indian analysts maintaining that a specific U.S. law was standing in the way of India’s scale-up of vaccine manufacturing. But beyond issues of overcommitment and exigencies lies a fundamental question: Is the Quad commitment to emerging tech a function of geopolitics, and an extension of sharpening strategic rivalries between Quad members and China? Or does the Quad see cooperation on emerging tech as means to provide a regional good to others in the Indo-Pacific? While the Quad, officially, so far has been cautious to the point of being coy about China, both proponents and opponents of the grouping would agree that the country looms large in how the grouping (implicitly) sees itself. And this is precisely where Quad ideation – whether that is on issues around emerging tech or other areas – would find few takers in, say, Southeast Asia where very few want to be drawn into a sharp China-U.S. rivalry despite obvious regional concerns about China’s territorial revisionism. To put it plainly: if the Quad embarks on tech standard evangelism in the region, for example, with the sole purpose of making sure that Beijing can be pushed out from the standard setting space, it is highly unlikely that many others would sign up to this program. Even more fundamentally lies the Quad members’ own individual commitments to tech innovation, and their plans and wherewithal to support it. Consider India which, on paper, has extremely favorable demographics: India has lots of young people (median age: 28.4 years), and innovators typically tend to be young, so as a matter of elementary logic and probability, the country should naturally be a leader in tech innovation. And yet, the country is far from being one for a host of reasons, including a sclerotic, outmoded educational system, weak intellectual property guarantees, and a risk-averse culture. Or consider Japan, with its aging population: Could that country (where more than 28 percent of the population is above the age of 65) reclaim the mantle of tech leadership and so arrest further economic stagnation? Or would the United States’ efforts to shape the innovation landscape – as part of its larger strategic reorientation directed at China – normalize state intervention in critical tech sectors, with unexpected second-order consequences across the Indo-Pacific? With due homage to former U.S. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld (who passed away last Thursday), the future of Quad tech cooperation involves both known unknowns as well as unknown unknowns. The walk has yet to be walked, even though the talk has been talked. | ||||||||

Japan to Create New Cyber Agency | ||||||||

| — Flickr, anthi tzakou | ||||||||

Japanese newspaper Yomiuri Shimbun reported on July 5 that Japan Post Holdings – which operates Japan Post – has created a new company, JP Digital, that will work towards “digital transformation” of all firms controlled by it. According to the newspaper, JP Digital will seek to do so “by issuing common IDs that are available for postal, banking, and insurance services offered by the group companies, developing unique smartphone applications, and digitalizing procedures for various services.” This development comes as many in Japan seek to shake up its often-obsolete, cumbersome practices that have – oddly enough for a country that is still considered by many in the Asia-Pacific as a tech hub – come in the way of business efficiency. Last September, Japan’s Minister for Administrative Reforms Kono Taro had ordered all government departments to dispense with the use of hanko stamps, ink seals that have to manually affixed to documents as official signature. Many see the seals as needless complication in the age of digital workflows inside and out of government across advanced economies. Despite Kono’s dictum, Japan’s hanko culture is likely to live on, demonstrating once again the stickiness of legacy practices in many parts of the Asia-Pacific. However, as has become crystal clear now, digitization and steep growth in the use of the internet by businesses, governments and individuals alike carry with itself specific, and increasingly growing, risks. On July 5, Sankei Shimbun weighed in on a recent decision to create a cybercrime bureau within Japan’s National Police Agency. According to the newspaper, the bureau, to be created in 2022, will have jurisdiction across Japan’s prefectures and will also coordinate with international partners in investigating transnational cybercrimes. The newspaper, while lauding the decision to create the new bureau, called it a first step towards creating a new Japanese cyber intelligence agency that will augment the capabilities of the Japanese armed forces as well as other government departments and agencies in meeting cyber challenges. | ||||||||

| Asia-Pacific Cyber Risks Stay tuned for a new DRI Monthly Report that surveys the Asia-Pacific cyber risks landscape. The report, drawing on primary and secondary research as well as expert consultations, surveys the geopolitical and commercial forces shaping Asia’s approach towards cybersecurity and the role of the COVID-19 pandemic in consolidating emerging cyber trends. It also highlights areas of critical importance for governments and businesses allowing them to act on tomorrow’s challenges today. | ||||||||

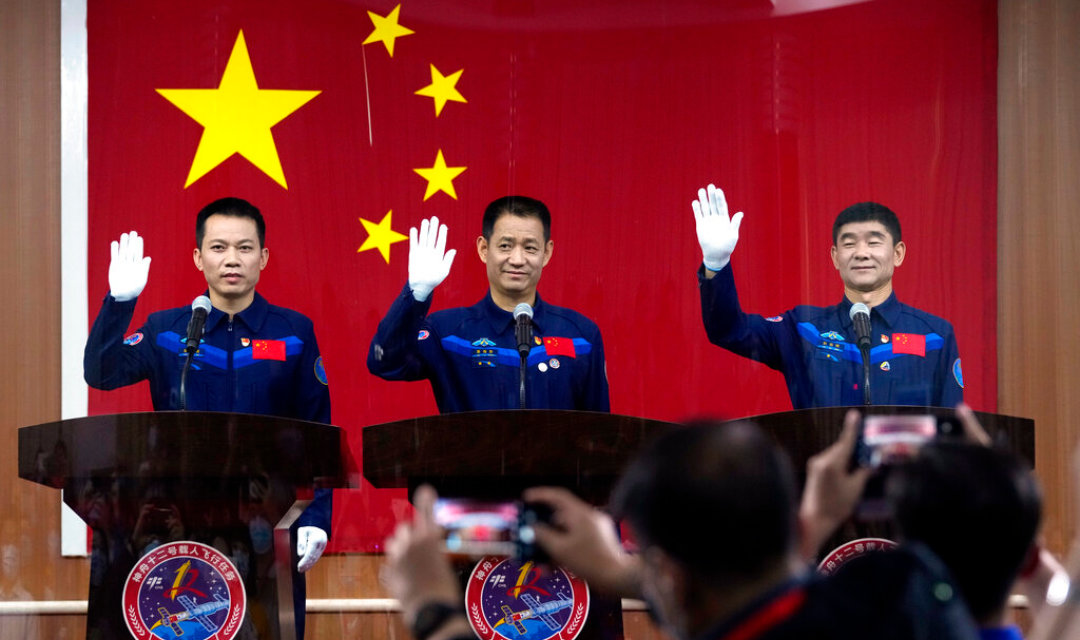

Chinese Astronauts Complete Space Walk | ||||||||

| Chinese astronauts, from left, Tang Hongbo, Nie Haisheng, and Liu Boming wave at a press conference at the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center ahead of the Shenzhou-12 launch from Jiuquan in northwestern China, Wednesday, June 16, 2021. | ||||||||

| — AP Photo, Ng Han Guan | ||||||||

Arguably, much of what is shaking up the tech landscape in the Asia-Pacific is China’s own dramatic push for new scientific and technological capabilities. Nothing demonstrates this better than the country’s burgeoning and increasingly impressive space program. On July 3 and 4, two Chinese astronauts conducted a spacewalk from the Tianhe main module of China’s under-construction space station. The two Shenzhou-12 astronauts installed equipment for the space station on their spacewalk, marking the second time Chinese astronauts have carried them out. China had launched the Tianhe main module to space on April 28 using a Long March-5B Y2 rocket; construction of the country’s space station is expected to be complete by late next year. In a March DRI Monthly Report on how Asia-Pacific powers look at outer space – through civil, military and commercial lens – analyst Namrata Goswami pointed out that China’s space program is an integral part of the country’s grand strategy, and while national pride remains a driver of China’s space ambitions, it is also strongly motivated by economic considerations. She wrote: “For China, investing in outer space moves beyond prestige and reputation, beyond a “flags and footprints” model of the Cold War. Instead, China aims to develop capacity for establishing permanent space presence, from which it would economically benefit in the long term.” At the same time, it is certain that China would leverage these new capabilities to build diplomatic clout back on Earth. Once fully functional, the Chinese space station will serve as a powerful symbol of China’s capabilities, and categorically illustrate the extent to which it seeks technological parity with the U.S. – something that will not be lost on smaller powers in the Asia-Pacific. And then of course there is China’s rhetoric around its space program in general, and the space station, in particular. It has already projected its space station as a site for international collaboration, as a pointed though oblique snub at the U.S. whose laws prevent NASA from collaborating with China, including on the International Space Station. One news article on China’s space station notes that six international and collaborative efforts have been approved to take place aboard. Bottomline: China’s space station is more than a space station. The recent spacewalks are small steps as a giant stride with far-reaching terrestrial implications quietly shapes up in the background. | ||||||||

DRI Monthly Reports are rigorous research investigations that go beyond reportage and commentary for deep-dive analyses of timely topics and emerging trends in the Asia-Pacific. | ||||||||

Emergent Engineering | ||||||||

| — Flickr, Ashok Boghani | ||||||||

It is surprisingly difficult to talk precisely about technology in general, without referring to particular ones. As complexity theorist Brian Arthur wrote in his excellent 2009 book, how tech evolves – and the specific abstract principles that govern them – remains something of a mystery. That said, as some have argued following the COVID-19 pandemic, any engineering solution that interact with complex adaptive systems – the economy, for example – must live with, and even thrive under, uncertainty rather than fight it. As Santa Fe Institute scientists Jessica Flack and Melanie Mitchell wrote last year, “[i]nstead of attempting to narrowly forecast and control outcomes, we need to design systems that are robust and adaptable enough to weather a wide range of possible futures.” How might such systems be designed? According to Flack and Mitchell, through emergent engineering, a set of principles that drawn from the study of complexity and inspired by the natural world. As their colleague David Krakauer wrote in a 2019 article, traditional engineering principles violate most properties of how complex systems work, leading to a manifestly odd situation where economies continue to be unstable, war and conflict remain common, and effective medicine for many diseases out of reach – all despite a seemingly unstoppable march of technology. Emergent engineering – “[a]n alternative approach that respects in its own axioms the properties of complex systems and builds on the insights of classical engineering” – is very much possible, he argues, by pointing to how vaccines, market auctioneering, and neuroprosthetics work. | ||||||||

Diplomat Risk Intelligence (DRI) is the consulting and analysis division of The Diplomat, the Asia-Pacific’s leading current affairs magazine. Learn More | ||||||||

For DRI services, contact us at: | ||||||||

Follow The Diplomat on:

| ||||||||

| This newsletter was sent to [[EMAIL_TO]]. Unsubscribe | ||||||||

| Diplomat Media Inc. | 1701 Pennsylvania Ave | Washington, D.C. 20006 | USA | ||||||||

| [email protected] | thediplomat.com | ||||||||

| ©2021 Diplomat Media Inc. All rights reserved. | ||||||||