| August 13, 2021 | dri.thediplomat.com |

| Democracy in Asia: Down and Out? | ||||||||

|

Welcome to the newsletter of Diplomat Risk Intelligence, the research and consulting division of The Diplomat, your go-to outlet for definitive analyses from and about the Asia-Pacific. Each week, DRI Asia Review focuses on a single country, subregion, or theme, based on in-house research, new DRI products, and regional media monitoring. It has four sections. The Big One offers DRI’s assessment of a major security, geopolitical, or economic issue. Babel is analysis based on translations of articles in regional newspapers and media outlets by a DRI team specializing in major Asian languages. In From Our Stable, you will find analysis based on new DRI products, short excerpts from them, or new multimedia features. And finally, each week Digestif will highlight a concept – from science, technology, economics and even philosophy – that will help you up your analytical game, irrespective of your professional interests. This week’s DRI Asia Review focuses on the state of democracy in Asia. We look at pro-democracy protests in Thailand, and the complicated relationship between voter turnouts and democratic norms consolidation there and elsewhere. Ahead of presidential elections in South Korea next year, we flag the latest instance that once again demonstrates President Moon Jae-in’s precarious political position. We offer a sneak preview of some of the conclusions in a new DRI Monthly Report on Asia-Pacific cyber risks. And we leave you pondering the narrow corridor of liberty that runs between state and social power. | ||||||||

Asia’s Wavering Democratic Arc | ||||||||

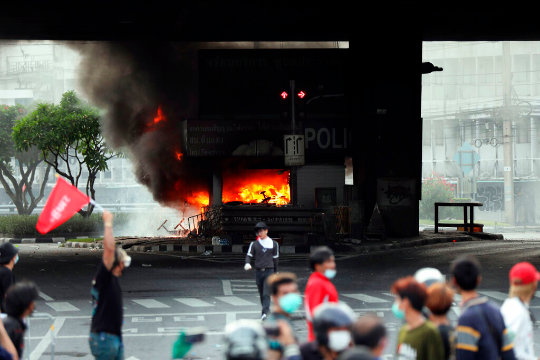

| Anti-government protesters set fire to a traffic police booth during protest in Bangkok, Thailand, Tuesday, Aug. 10, 2021. | ||||||||

| — AP | ||||||||

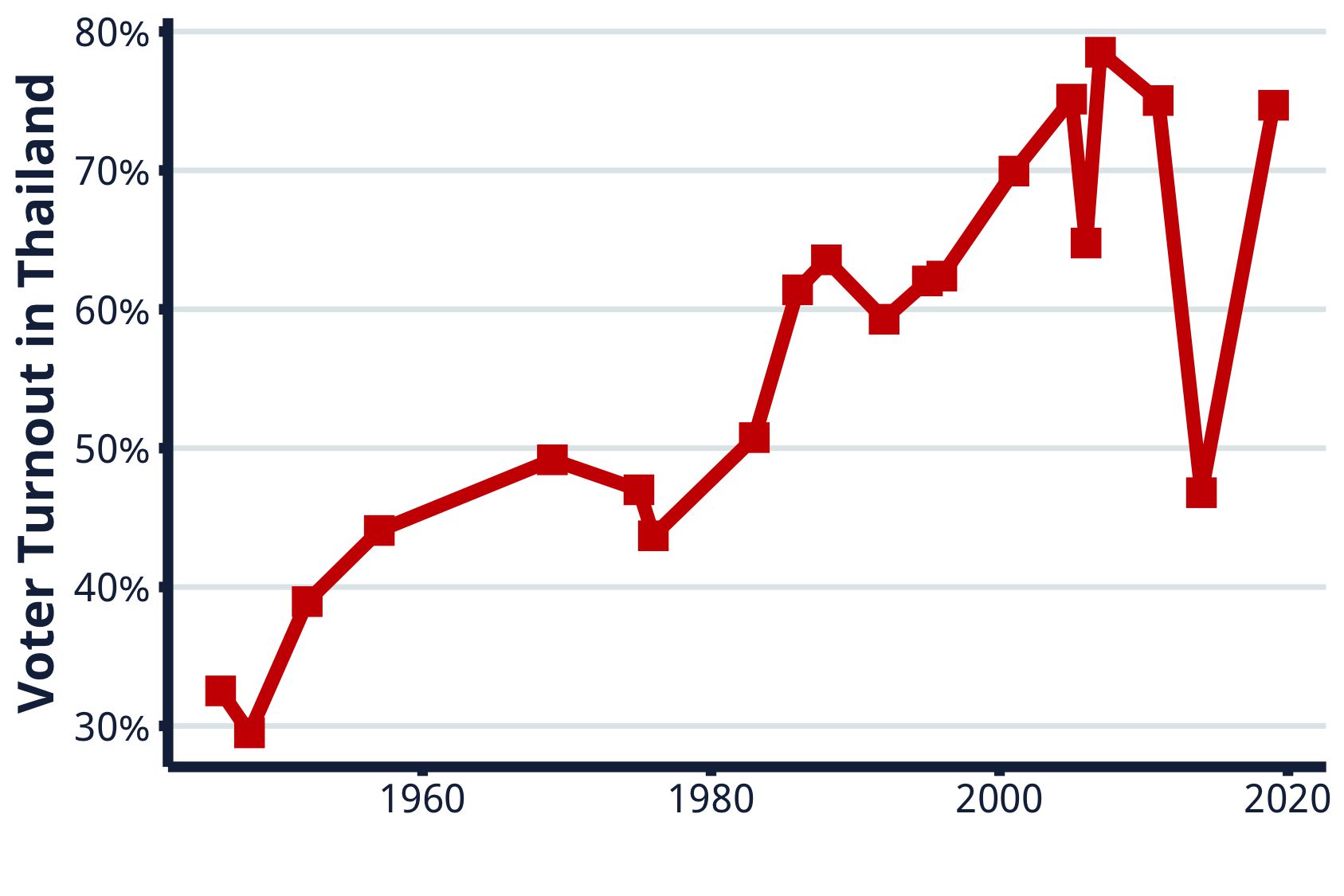

The August 10 clashes between protestors and the police in Bangkok once again highlights the precarious state of democracy and vice-like grip of authoritarian forces in Thailand. Tuesday’s violent protests against the Thai government’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic saw the police using water cannons and tear gas to disperse protestors. Six police officers were injured in the clashes, including from bullets and home-made bombs. The clashes come on top of an on-going pro-democracy movement in Thailand, with protestors taking aim not only at Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha and his government, but also at the country’s hallowed (and yet, increasingly dysfunctional) monarchy. In turn, the Thai government has responded in a ham-fisted way to crack down on activists leading the protests, making the possibility of a negotiated settlement of grievances between pro-democracy activists and the Prayut government remote. “It appears that the Thai state has now adopted zero tolerance for dissenting voices. One year after the rise of youth-led democracy uprising, the prospect for compromise or reconciliation is now fading away. Thailand is descending into new chaos,” Human Rights Watch’s Sunai Phasuk told Al Jazeera on August 10. Thai politics is not for amateurs, as the country’s complicated political twists and turns since the establishment of a constitutional monarchy in 1932 continue to baffle all but the most seasoned observers. That said, the proximate triggers for the current protests are easy to discern: increasing public discomfort with Thailand’s hybrid democracy (Prayut is a former military junta leader who had previously governed Thailand for five years following a 2014 coup) as well as with a profligate and morally dissipated monarchy whose stock among the country’s young continues to fall rapidly. Thailand also serves as an interesting example of how voter turnout in many countries in the Asia-Pacific has not correlated with deepening of democratic norms and practices. Writing in a 2014 book chapter, Prinat Apirat observed that “[Thai] people’s active political participation beyond voting in national elections remains elusive and democratic consolidation remains a distant goal …” That continues to be the case seven years later.

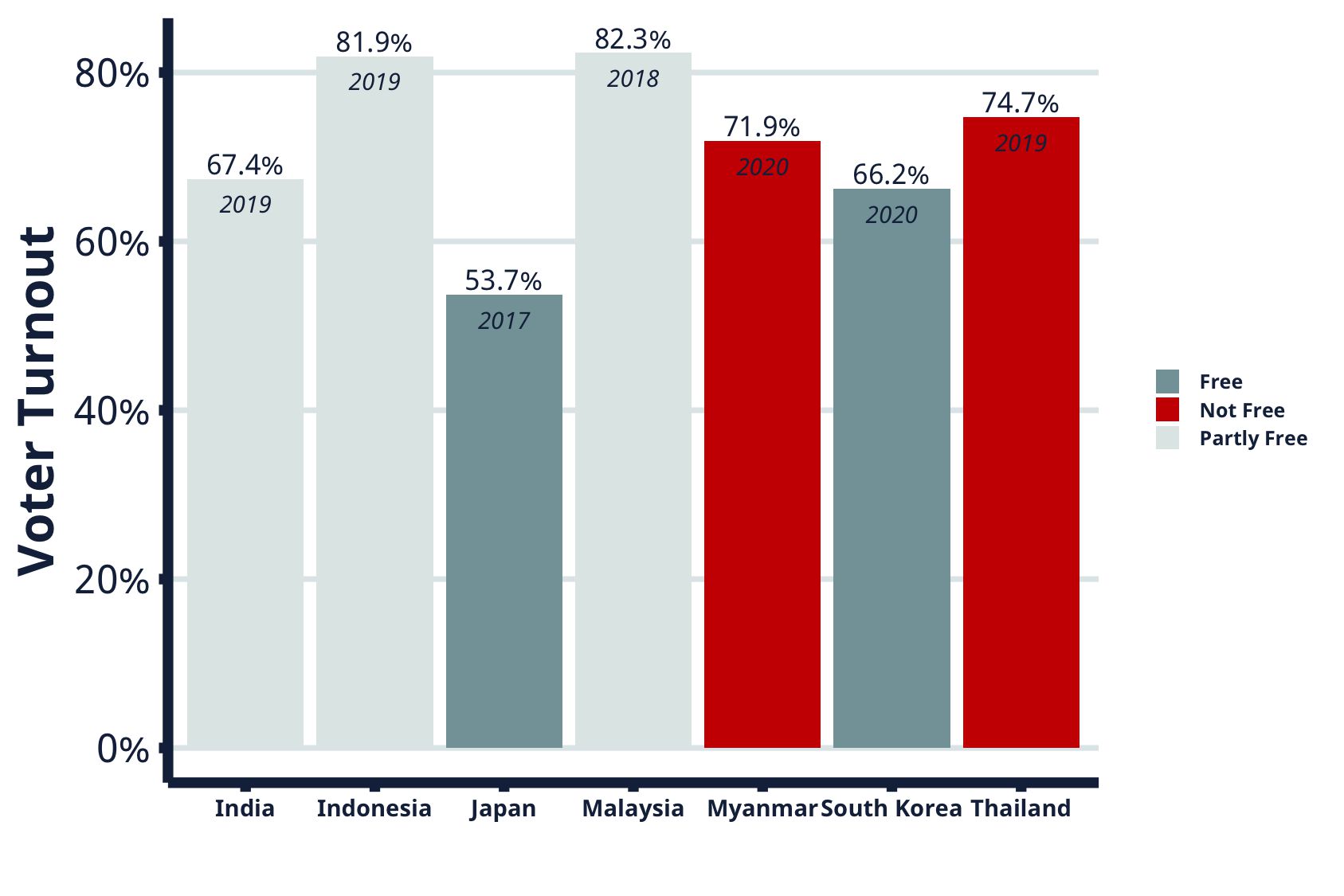

The lack of correlation between the state of freedom in general across the Asia-Pacific and voter turnout figures is also clearly visible when we juxtapose Freedom House rankings for the former against the latter. Consider, as an example, Indonesia -- a country the latest Freedom in the World report described as being “partly free.” And yet, the 2019 parliamentary elections in Indonesia saw a staggering 81.9 percent of the eligible population cast their ballots. The observe to this observation is equally interesting. For example, Japan has a rich, deep democratic tradition that cuts across many spheres of public life. However, the voter turnout in the 2017 elections in that country was only 53.7 percent.

At the same time, high voter turnouts also do not mean that authoritarian forces in many countries around the region will respect electoral verdicts. Consider the case of Myanmar, which saw a turnout of 71.9 percent in elections last year, returning State Counsellor Aung Sun Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy to power. To be fair, the elections themselves were far from being perfect in how they were conducted, amid COVID-19 restrictions and internet shutdowns in the Rakhine and Chin states. The NLD itself is no exemplar of democratic values, as it leveraged ethnic Burman nationalism for electoral gains and turned a blind eye to the Tatmadaw’s atrocities against the Rohingya in particular. That said, it is the Myanmar military’s astonishing appetite for power that is what is truly remarkable about that political scene in that country. The military already had a privileged place in the country’s political arrangements, with the 2008 constitution guaranteeing it control over several key ministries, along with a quarter of seats in the parliament. None of this proved to be enough for the junta which – under manifestly flimsy and legally dubious grounds – overthrew the elected government after jailing key political leaders in February this year. While the exact reasons behind why the junta did what it did remain unclear more than six months later, a February CSIS assessment that the “coup seems a result of [Senior General Min Aung Hlaing]’s personal ambitions” seems to be as good a guess as any. | ||||||||

Webinar: Asia-Pacific Cyber Landscape Stay tuned for the inaugural DRI Majlis – our monthly webinar that brings together best-in class experts to examine vital issues – on Thursday, August 19. The webinar will look at the Asia-Pacific cyber risk landscape and address the geopolitical and commercial forces shaping the region’s approach towards cybersecurity. It will also delve into role of the COVID-19 pandemic in consolidating emerging cyber trends. | ||||||||

South Korea’s Moon Draws Flak from Former Official | ||||||||

| South Korean President Moon Jae-in at his first press conference, May 10, 2017. | ||||||||

| — Flickr, Republic of Korea | ||||||||

Ahead of presidential elections next year, South Korean President Moon Jae-in recently drew harsh criticism from a former senior official and presidential hopeful. On August 9, South Korean newspaper Dong-a Ilbo reported that former Director of Board of Audit and Inspection (BAI) Choi Jae Hyung – by way of criticizing the Moon administration’s policy to phase out nuclear power – opined in a Facebook post that the “Moon Jae-in cabinet has committed ideological, political, social and economic attacks in all areas.” He went on to add that it has also “damaged the value of the Constitution, shaking the market economy, choking the media and infringing upon the freedom of the people.” “Political rookie” Choi had clashed with Moon in the past about the president’s nuclear power policy, leading him to resign from BAI last month. Meanwhile, Moon’s approval ratings have plummeted in his final year in office, down to 29 percent in the April Gallup poll from 70 percent (according to some polls) a year ago. This reversal of fortunes has stemmed from public perception of his mishandling of the COVID-19 pandemic. In a tribute to Satsuki Eda in Asahi – who passed away on July 28 at the age of 80 – economist Eisuke Sakakibara summarized the veteran political leader and lawyer’s career, with Asahi calling Satsuki a “life embodying Japan’s post-World War II democracy.” Satsuki Eda, son of late Saburo Eda, former secretary-general of the Socialist Party, was born on May 22, 1941, in Nagaoka in Okayama City. After a long and successful career as a lawyer-turned-legislator, he retired from politics in 2016. He was first elected to the Upper House of Japan’s Diet in 1977 and served four terms there elected from different political parties. In 1998 he joined the newly formed Democratic Party of Japan and was picked Upper House president in 2007. He held several ministerial posts, including as ministers for justice and the environment, in various cabinets. Before retiring, he served as top advisor of the Democratic Party. Meanwhile, Japanese Prime Minister Suga Yoshihide’s political future ahead of the October elections looks bleak, following the recently concluded Olympics amid a surge in COVID-19 cases. | ||||||||

Democracy and Cyber – An Uneasy Mix? | ||||||||

| — Flickr, Jason Howie | ||||||||

Technology’s relationship with the diffusion of democratic norms and values has always been two-sided. While online spaces and social media have empowered several marginalized communities and served as platforms for political, economic, and social engagement, they are increasingly being used by states and non-state actors as tools of digital repression. Asia is no exception to this global trend. Arbitrary internet shutdowns and stringent censorship measures are no longer confined to traditionally autocratic regimes like China or North Korea. Instead, they have become ominous features of governance in several other countries including India, Pakistan Sri Lanka, the Philippines and Indonesia, just to name just a few. In July, a global consortium of journalists -- building on previous work by the University of Toronto’s Citizen Lab -- put forth evidence suggesting brazen deployment of the Israel-made Pegasus spyware to conduct surveillance on journalists, activists, opposition leaders and others dissenting against governments in several Asian countries. The countries that allegedly deployed the military-grade spyware included India, the UAE, Qatar, Bahrain and the Central Asian nations of Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan, the consortium of journalists claimed. In the latest Diplomat Risk Intelligence Monthly Report, Dense Grey Webs: Cyber Risks and Trends in the Asia-Pacific, three key risks to digital democracy in Asia were delineated and analyzed. First, the report flagged the role of artificial intelligence (AI) as a surveillance “force multiplier,” through the development of facial recognition technologies. AI could also lead to proliferation of disinformation campaigns, especially through the deployment of deepfakes, the report concluded. Second, the report evaluated the role of malign state and non-state actors in disinformation campaigns abroad. The core risk posed by these campaigns is to the integrity of electoral processes. These campaigns often also undermine public confidence in the political establishment. In addition, the rise of such influence operations has caused states in Asia to adopt measures that lawyers and civil society activists have decried as excessive censorship. Third, the report surveyed digital trends consolidated by the COVID-19 pandemic. It identified privacy and security risks brought about for employees, consumers, and citizens in general increasingly working and living online. Such risks arise out of deployment of surveillance and contact-tracing applications, including through those promoted by regional governments. | ||||||||

| ||||||||

The Narrow Corridor | ||||||||

| — Flickr, Dushan Hanuska | ||||||||

In a 2019 book, economists Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson investigated a “narrow corridor” of liberty – a Goldilocks zone, so to speak, between power of the state and power of society. Their idea is simple, elegant and powerful (ignoring the feeble pun): a state that is weak will be unable to guarantee security of its citizens; a state that is too powerful will end up despotic, negating their freedoms. Between the two lies a narrow corridor leading to a “shackled Leviathan” -- a “state that creates liberty” despite being extremely powerful, and one whose behavior is shaped by widely accepted norms. Acemoglu and Robinson, however, write that there is no single way through which a country could be transformed into a shackled Leviathan. Historical uniqueness and possible political and social tradeoffs between the state and society all play key roles in how a country could enter the narrow corridor. “True democracy and liberty don’t originate from checks and balances or from clever institutional design. They originate [and are sustained] in the much more messy process of society mobilizing, people defending their own liberties, and actively setting constraints on how rules and behaviors are imposed on them,” Acemoglu told MIT News on the occasion of the release of his new co-authored book in 2019. | ||||||||

DRI’s Director of Research Abhijnan Rej, Research Analysts Malvika Rajeev and Rushali Saha, and External Expert Arindrajit Basu contributed to this edition of DRI Asia Review. Translations of South Korean and Japanese media articles were provided by an in-house team of linguists. | ||||||||

Diplomat Risk Intelligence (DRI) is the research and consulting division of The Diplomat, the Asia-Pacific’s leading current affairs magazine. Learn More | ||||||||

For DRI services, contact us at: | ||||||||

Follow The Diplomat on:

| ||||||||

| This newsletter was sent to [[EMAIL_TO]]. Unsubscribe | ||||||||

| Diplomat Media Inc. | 1701 Pennsylvania Ave | Washington, D.C. 20006 | USA | ||||||||

| [email protected] | thediplomat.com | ||||||||

| ©2021 Diplomat Media Inc. All rights reserved. | ||||||||