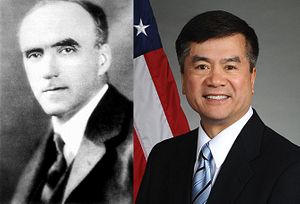

I am teaching a U.S.-China relations course this semester. When students and I discussed the bilateral relationship during the Chinese Civil War, the topic of John Leighton Stuart, the U.S. ambassador to China at the time, was raised. To my surprise, none of my American students had ever heard of him, but Stuart is very famous in China even among today’s young Chinese. During this course, we also talked about the current U.S. ambassador, Gary Locke. Unlike Stuart, my American students are familiar with Locke, but they were unaware of his behavior and the controversies regarding his ambassadorship in China. This produces two interesting topics for discussion: how U.S. ambassadors can influence China and why Americans know so little about the actions of their representatives in other countries.

I believe John Leighton Stuart was the most special ambassador the U.S. ever sent to China. As Lin Mengxi, a Chinese historian, once wrote, there was no other American of his ilk in the 20th Century, one who was deeply involved in Chinese politics, culture, and education and had such an incredible influence in China. He was born in China to American missionary parents. Growing up in China made him so familiar with the country and its language that he even wrote poems in Chinese. The most important part of Stuart’s legacy in China was Yenching University, where he was the inaugural president until his appointment as U.S. ambassador to China in 1946. Yenching University played a significant role in China’s modern history because many Chinese, including senior officials from both the Nationalist and Communist camps, were educated there. Despite this impact, Chairman Mao closed the university in 1949 because he despised its religious affiliation. Peking University took over the university’s physical campus and most of its departments in 1952. Therefore, Peking University, which has profoundly influenced China’s contemporary history, is a continuation of Yenching University.

Also in 1949, Stuart almost changed history. When the PLA conquered the Nationalist capital Nanjing in April, all of the ambassadors, except Stuart, fled with the Nationalist government to Guangzhou. Stuart sought accommodation with the Communist Party in an effort to maintain U.S. presence and influence in China. Unfortunately, these efforts failed, and he was called back to the States.

Which brings us to the legacy of current U.S. Ambassador Gary Locke, who is set to relinquish his post this weekend. Unlike Stuart, Locke does not speak Chinese. However, this language barrier did not impede his efforts to influence China. A recent article from a major Chinese website used the title, “Gary Locke’s Report Card: Let the 1.3 Billion Chinese Know About PM 2.5.” Shortly after Locke arrived in China in 2011, the U.S. Embassy in China began providing daily air pollution updates. Such air quality monitoring data differed completely from China’s normal weather broadcasts. For instance, this data used a new measurement called PM 2.5, air pollutant particles generally produced by the burning of fossil fuels and small enough to invade even the smallest airway. The embassy’s daily updates disclosed the degree of Beijing’s air pollution, which immediately drew Chinese attention to it and sparked discussions. Many Chinese reposted the data onto social media websites, spreading this information far and wide. People also realized the harm of Beijing’s air quality to their health. Moreover, the PM 2.5 data and public opinion put great pressure on the Chinese government to take action. Now many Chinese cities, Beijing included, have begun to release their own daily PM 2.5 data. Beijing also recently announced an ambitious plan to combat air pollution. Therefore, when Gary Locke announced his resignation, many Chinese commented that his biggest contribution was making people aware of PM 2.5 and the health risks of air pollution in large Chinese cities, including the nation’s capital.

In 1949, Chairman Mao wrote a famous article on Stuart called “Farewell, Leighton Stuart,” which is included in official middle school textbooks in China. Mao associated Stuart with the United States’ “cultural aggression” in China. Mao was worried about Stuart’s influence, particularly on intellectuals. And history sometimes repeats itself, because much of China’s official media often use the term “United States’ cultural aggression” to refer to Gary Locke’s actions in China. For instance, Locke carried his own luggage when he arrived in Beijing and he took economy class flights when traveling in China, which embarrassed the Chinese government. Chinese state media believes that such actions were part of a strategy to make the Chinese people compare Locke with corrupt Chinese officials. It is interesting that the behaviors of two different ambassadors from two different time periods were both called cultural aggression by official Chinese media. This indicates that Beijing still lacks confidence and worries about people, especially intellectuals, being influenced by America’s culture and values, in a way that could be dangerous for the Chinese government.

At the same time, these two ambassadors’ histories in China indicate that while they influenced China, they could not do much to help Americans better understand China. If we look at a list of past United States ambassadors to China, from pre-1949 diplomats such as Leighton Stuart, to the liaison office chiefs including George H.W. Bush, to more recent ambassadors like Stapleton Roy and Clark Randt, each has a special China story and left legacies there. Unfortunately, however, it seems that the Chinese are far more familiar with the U.S. ambassadors than Americans generally are. Some of the ambassadors are even misunderstood by their own people. Ambassador Stuart spent his later years in poverty and under suspicion by McCarthyism.

Often people want their ambassadors to be a hero to challenge the regime in China. However they forget their representative’s main role is to manage communication and cooperation between the two governments and two countries. Under pressure from “domestic opinions” in the U.S.– and driven by their own personal political ambitions– some ambassadors’ behavior has crossed the line of proper diplomatic conduct. Jon Huntsman’s unusual appearance at the site of a planned pro-democracy protest in Beijing in February 2011 is one such an example. Gary Locke’s actions to help Chinese dissident Chen Guangcheng to escape from house arrest and seek refuge in the U.S. Embassy in April 2012 are also highly controversial.

As noted, Gary Locke’s ambassadorship officially ends on Saturday. There were a lot of discussions about his “unusual” resignation, as he only served for two years. Half-jokingly, some Chinese wondered if Beijing’s air pollution might be to blame for Locke’s early resignation. Interestingly, even before Max Baucus, the new ambassador, goes to Beijing, China’s microbloggers have already given him a Chinese nickname based on the pronunciation of his name: Bao Kesi (包咳死), meaning “cough to death.”

Zheng Wang is an Associate Professor in the School of Diplomacy and International Relations at Seton Hall University in New Jersey. He is also a Global Fellow at the Kissinger Institute on China and the United States of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars.