For those who are getting bored with the traditional “green” versus “blue” divide in Taiwan’s politics, things are becoming a lot more interesting with the return to Taiwan, after 17 years in exile, of the most-wanted fugitive-turned-politician Chang An-le in June 2013. Since his return, Chang, a former leader of the Bamboo Union triad and founder of a pro-unification party, appears to have embraced Taiwan’s democratic system by appearing on TV shows and opening campaign offices around the country. But old habits die hard, and the 65-year-old has resorted to threats and intimidation to leave his mark on local and national politics.

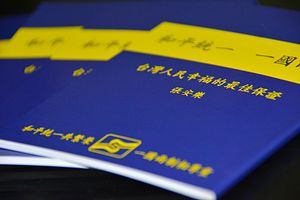

The White Wolf, as Chang is also known, returned to Taiwan in late June 2013, and was promptly arrested at Taipei International Airport (Songshan) by police officers. Hours later, he was released on NT$1 million (about US$30,000) bail, and immediately embarked on a campaign to spread his “peaceful reunification” propaganda, which he had condensed into a small blue booklet. Since then, Chang has opened a number of political offices around the country, with no known date for court appearances.

Regarded as Taiwan’s most educated gangster, Chang served about 10 years in a U.S. jail on drug trafficking charges and was also indirectly implicated in the 1984 murder of Henry Liu in Daly City, California. According to Ko-lin Chin, author of Heijin, after being deported to Taiwan in 1995, Chang was involved — again indirectly — in a bid-rigging case, and fled to China in 1996 during Operation Chih-ping, a nationwide campaign launched by then-president Lee Teng-hui against criminal groups.

With no court date having ostensibly been set, and free of interference by the Taiwanese authorities, Chang is a free man and is making the best of his time to become a participant in Taiwan’s politics. Ironically, while the former most-wanted criminal is left alone by the legal system — even when he shows signs, as we shall discuss, of engaging in old practices — young Taiwanese activists are increasingly weighed down by battery and obstruction charges for very minor offenses committed during peaceful protests, double standards that raise serious questions about the even-handedness of the legal system here.

Chang, who made various contacts with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) during his exile in China, is openly pro-unification. A visit to his Taipei office late last year confirmed this, with the presence of a large People’s Republic of China (PRC) flag and several dozen photographs of him meeting various CCP officials. Observers of China’s United Front work have long warned about Beijing’s use of criminal organizations to facilitate “reunification” and of the possibility that agents would seek to turn Taiwan’s democracy against itself to do so. With Chang’s return to Taiwan, Beijing seems to have found both in a single individual.

If Chang were limiting his activities to appearances on talk shows — where he’s fared rather poorly — opening offices, having photo ops with local KMT legislators, and engaging in philanthropy, his participation in local politics wouldn’t be overly troubling. (Though Kuo Kuang-ying, one of his close aides, is a former director of the information division at Taiwan’s representative office in Toronto who was recalled, and eventually fired, after it was revealed that he had penned, under a pseudonym, several articles viciously demeaning Taiwanese people. Upon his return to the country in 2009, the Bamboo Union sent bodyguards to Taiwan Taoyuan International Airport to ensure his safety.)

But unfortunately that isn’t the case. The man who is believed to have remotely orchestrated flash protests against the Dalai Lama when the Tibetan spiritual leader visited Taiwan in 2009 and provided security to Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) officials during elections is now dirtying himself with a series of comments that have no place in a democracy.

Chang’s first known troubling move occurred in early November 2013, when he threatened to deploy 2,000 of his followers to protect President Ma Ying-jeou and other KMT officials amid a shoe-throwing campaign of protests spearheaded by an self-help group for laid-off workers. (Interestingly, neither the KMT nor law enforcement authorities said anything about Chang’s “offer”). As the threat failed to deter the protesters, who were planning a mass rally in Greater Taichung, the site of a KMT party congress on November 10, Chang changed course and offered money to the protesters in exchange for their abandoning the planned activities. On two occasions, one of the protest organizers, a young woman, was called into an office for “discussions” with Chang’s people. Although that tactic also failed and the protest went ahead, there is reason to believe that the implicit intimidation led the organizers to cancel certain planned activities.

Later that month, members of Chang’s group routinely turned up at the many protests coordinated by civic organizations — including the Black Island Youth Alliance, created to oppose a controversial Cross-Strait Services Trade Agreement — during a visit by Association for Relations Across the Taiwan Strait (ARATS) Chairman Chen Deming. Once again, the presence of such individuals intimidated the protesters and made them fear for their personal safety, thus undermining their democratic right to hold protests.

Things took on a much more sinister hue in late February 2014 after a group of pro-independence activists angered with recent government policy decisions felled a bronze statue of Sun Yat-sen, seen as the founder of the Republic of China, at a park in the southern city of Tainan. During a press conference the following day, Chang retaliated by threatening “war” against Taiwanese independence groups, including the World United Formosans for Independence (WUFI), a pro-independence organization that, as far as we know, had nothing to do with the statue incident (the Alliance of Referendum for Taiwan was responsible). The next day, Chang showed up at the park bearing flowers and vowed to “take action” against Tainan Mayor William Lai of the DPP, who also had nothing to do with the toppling of the Sun statue, if he didn’t apologize within two weeks and ensure it is restored. (Pictures of a scuffle involving members of the Alliance and Chang’s followers at the site suggest that the latter, clad in black and bearing tattoos, were organized crime elements.) Once again, Chang was making veiled threats against members of society, this time the elected mayor of a pan-green city.

All of this has occurred without law enforcement authorities or the Ma government lifting a finger to prevent Chang and his followers from threatening Taiwan’s citizens, a great discredit to an administration that came into office in 2008 vowing to launch a new era of “clean politics.”

With seven-in-one local elections scheduled for the end of 2014, and presidential elections in 2016 — in which Chang has vowed to field candidates — there is every reason to fear that similar intimidation, implicit or overt, against people who oppose unification (candidates and voters) will become a factor. The impact on the quality of Taiwan’s imperfect democratic system, not to mention on the electoral outcomes, could be important, especially if, as is widely believed, Chang is doing Beijing’s work. Beijing has made little secret of its intentions to discredit Western democracy as an alternative to its repressive model in China. Moreover, the active involvement of gangsters in street politics will also have an impact on public safety and can only undermine social stability.

Chang advocates “peaceful” unification, but his techniques whenever he encounters opposition, and the democratic checks and balances that Taiwanese society now enjoy, are anything but peaceful. This alone should be enough to make anyone who cares about Taiwan’s future, not to mention the island’s ability to serve as an example for China’s 1.3 billion people, pay attention.