The prospect of greater Chinese involvement in the Middle East peace process was raised in mid 2013 when Beijing invited both Israeli and Palestinian leaders for separate meetings to discuss the resumption of the Arab-Israeli peace process. Newly elected Chinese leader Xi Jinping used the meetings to unveil his four-point peace proposal for the settlement of the Palestinian issue. Although it might seem that his peace plan contains nothing new, this offer to be the intermediary in a peace discussion signals the willingness of China to be involved in Arab-Israeli affairs going forward.

This plan is much greater than the sum of its parts, since it pinpoints a real eagerness on China’s part to be a stakeholder in the persistent Middle East problems.

Although the Chinese will not be able to magically eliminate all hindrances standing in the way of peace negotiations, by virtue of their neutral interactions with both the Arabs and the Israelis as well as their relationship with other major forces in the Middle East, like Hezbollah and Hamas—which the West declines to cooperate with—Beijing would seem to be capable of facilitating and injecting new vitality into the peace process.

Given Washington’s pro-Israeli stance, which has long been viewed negatively by Arab communities and indeed most of the world, China has an advantage. It could offer an incentive for the Israelis to comply with some Arab demands in return for Chinese backing on issues relating to Iran, in particular.

China’s lack of aggression in the region is arguably another reason for Arabs to be optimistic about Beijing’s support for the Palestinians. Unlike the Americans, the Chinese have never initiated a pre-emptive war in the region, and distinct from the European powers, China has never directly controlled territory in Southwest Asia. Beijing also has no record of anti-Semitism that could obstruct its future relationship with Israel. This lack of any imperial or anti-Semitic history in the region could enable Beijing to offer itself as a new actor in Arab-Israeli affairs.

Moreover, encouraging negotiations through the economic integration of Israel and Palestine seems to be a feasible approach, and China could raise its investment and boost economic alliances with both states. Its economic clout could give Beijing the means by which to effectively pressure the two sides to move forward towards a lasting solution.

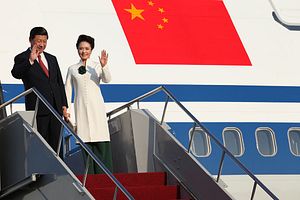

Another aspect that would likely contribute to the success of China’s involvement in the Palestinian issue is the stability of its leadership. Barring unexpected events, Xi Jinping will be the leader of the Chinese People’s Republic for the most of the next decade, and while his successor will differ in personality, the fundamental political principles will likely be the same.

This is in sharp contrast to the efforts of the Americans at mediating the Arab-Israeli problem, where a new administration can completely change the subtleties on the ground. History amply demonstrates this, with President Bill Clinton’s last-ditch attempts at peace talks during the declining weeks of his administration largely set aside by his successor, George W. Bush.

Similarly, President Bush took up the Arab-Israeli peace process in his second term only to see President Barack Obama pursue a foreign policy that has been dominated by his embrace of the Arab Spring, and then to have his attention diverted by the continuing Syrian turmoil and potential conflict with Iran. With the Chinese as mediator, it would not be necessary to press the reset button with each change in government.

Another facet that makes China stand out is its lack of ideology when it comes to the Arab-Israeli conflict. Chinese civil society simply does not have activists or lobbyists like the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC) or similar pressure groups with given political or religious ideologies that can exert considerable influence over U.S. foreign policy. These groups have frequently used their power and influence to frustrate efforts by policymakers to hold Israeli responsible for actions that breach international law and scuttle efforts for peace, most significantly the continued construction of Israeli settlements in Palestinian territory.

Although in recent years there have been efforts made by Israeli advocacy groups in Chinese academia to influence public opinion in China, it remains unlikely that such initiatives will bear any tangible fruit in the near future. In the meantime, China simply does not have to deal with independent organizations attempting to obstruct its foreign policy goals, or with the blowback of public opinion in taking up a peace initiative.

After a long wait for an effective partner for peace, the Middle East may find reason to welcome Chinese involvement.

Muhammad Zulfikar Rakhmat has lived in the Middle East for seven years. He holds a B.A. in International Affairs from Qatar University and is currently a research assistant at the same university.