Prime Minister Narendra Modi broke new ground last Monday by inviting the leaders of “every nation on India’s periphery” to his swearing-in ceremony. These countries included all the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) countries as well as SAARC observer Mauritius. Even the Prime Minister in exile of Tibet was invited. Despite this impressive guest list, the leader of one of India’s neighbors, Myanmar, was not invited.

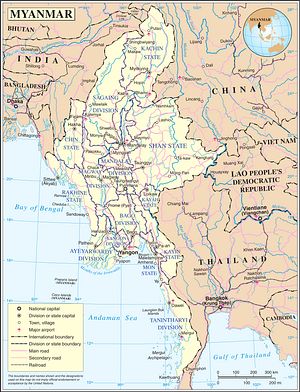

This fact is made all the more glaring because the omission of an invite seems to go against the new government’s desire to cultivate more substantial relations with its neighbors. India and Myanmar share a long 1,624-kilometer (1,009 mi) border. However, in all likelihood, the lack of an invite for Myanmar’s President Thein Sein was not a mistake or a deliberate omission, but simply something that was on nobody’s mind. Politicians and the media in both countries did not seem to expect that Myanmar would even be invited, as evidenced by the fact that the media in neither country made an issue out of Myanmar’s non-invite.

This is a function of how both countries view each other. Despite the fact that Myanmar is an observer in the SAARC, it does not have strong ties with South Asia and is more oriented towards Southeast Asia, where it is a member of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). From the vantage point of New Delhi too, policy toward Myanmar is treated not through the lens of South Asian bonhomie but under the aegis of India’s Look East Policy. This lack of closeness may come as a surprise to some, but despite rhetoric about historical, cultural, and religious ties, Myanmar and India went different ways centuries ago with Myanmar drawing closer to Thailand and China. After the British conquest of Burma in the nineteenth century, what is today’s Myanmar was ruled as a province of British India but was separated and made an independent colony in 1937, largely at the demand of Burmese nationalists who did not identify with the nationalist Indian independence movement.

Relations with Southeast Asian countries, including Myanmar, will undoubtedly be given more priority in the upcoming few months. The previous Congress government unfortunately neglected India’s relations with its Asian neighbors, its elite English-speaking and Western-educated leaders seemingly forgetting that India is in fact in Asia and not in the West — a psychological orientation reflected in external policy. The Indian nationalist narrative reflected in BJP thinking is, on the other hand, more oriented towards Asia. To begin with, India will seek greater connectivity with Southeast Asia and land routes must necessarily pass through Myanmar. India has recently called for a bus route from Imphal in Northeastern India to Mandalay in Myanmar. Potentially more important is Myanmar’s location between India and China. Prime Minister Modi is especially keen on improving India’s lukewarm relations with China, which had experienced glacial progress under the previous government. Congress may have deliberately misinformed the public of the nature of India’s past interactions with China in order to create a sense of martyrdom to cover up for its failures during the 1962 Sino-Indian War. In a recent conversation with Modi, Chinese Premier Li Keqiang warmly suggested the construction of a Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar (BCIM) economic corridor that would connect Kunming in China to India’s Northeast through Myanmar.

Such a connection to Myanmar, Southeast Asia, and China would be a boon to India’s much neglected Northeast region. Northeast India is significantly different from the rest of India in terms of languages, religion, culture, and even race and is in many ways more Southeast Asian than South Asian. Surrounded by Myanmar, China, and Bangladesh on almost all four sides and connected to the rest of India via only a narrow corridor, greater interconnectivity with international neighbors could bring this region much needed economic development and stem the dozens of insurgencies that have plagued the area for the past 60 years. That the Modi government means to improve the situation in Northeast India is clear by the appointment of a seasoned former general, Vijay Kumar (VK) Singh to the federal Ministry of Development of North Eastern Region (MDONER). Singh is expected to infuse some much needed dynamism into the region.

The Modi government’s initial focus on its neighbors in South Asia is not at odds with improving relations with Southeast Asia. The Look East Policy was a cornerstone of the previous BJP government and in all likelihood will be given more importance under Modi, given his marked interest in pursuing stronger relations with his eastern neighbors. However, the Look East Policy makes more sense if it occurs in tandem with economic integration in South Asia, as it makes little sense for India to liberalize trade with Southeast Asian countries without pursuing a similar policy in its own backyard. This is why South Asia has been accorded the greater initial priority, especially since economic integration and bilateral trade in the region is currently miniscule.

Akhilesh Pillalamarri is an Editorial Assistant at The Diplomat.