“[T]he removal of Saddam Hussein was the beginning, not the culmination, of a long a very uncertain process of reform,” academic Toby Dodge wrote in his 2003 book Inventing Iraq: The Failure of Nation Building and a History Denied. Presciently, Dodge continued: “It was also the continuation of a failed effort to create a modern liberal state on the part of the world’s leading hegemon as part of a new world order.” 11 years on, that effort has again failed.

For a while it looked like the second “mission accomplished” — this one not Bush’s but Obama’s — had a certain ring of truth to it. Delivering on his promise to pull U.S. soldiers from Iraq and facing an American public that was exhausted after a decade of two foreign wars, President Obama and his White House declared victory in Iraq, having installed an essentially functional government and trained Iraqi police and soldiers, at the cost of more than $15 billion, to ensure future stability.

But then history returned to haunt Washington, and in many ways the monster that now threatens stability within the entire region is even more terrifying than its predecessor, who was unseated and then executed by the Coalition and their Iraqi allies. It first emerged in the slaughterhouse of the civil war in Syria, and then it came galloping across the border into Iraq. Soon thereafter, the group, known as the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria, or ISIS, was taking over cities and entire swathes of Iraq, its militiamen using guns and light armored vehicles. The world has recoiled in horror as it learned more about the tactics used by the extremist organization, which include mass murder and the decapitation of non-Sunni men, women and children.

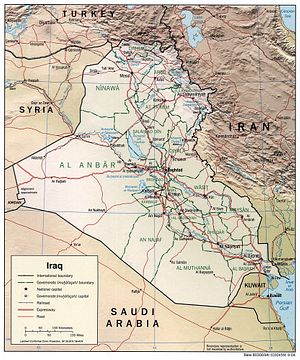

The rise of ISIS is a stark reminder of Bush and Obama’s failure to help create a modern democratic state in Iraq. But to be fair, other elements were responsible for the new nightmare that has descended upon innocent Iraqis. Among them is the cause that Washington seems to want us to believe was the principal one: the failure of Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki, who stepped down last week, to create a government that was inclusive enough that the minority Sunni Iraqis, who account for 32 to 37 percent of the total population of 31.2 million, didn’t feel excluded. By failing to accomplish this, Maliki, of the Shia majority (60 to 65 percent of the population), was accused of fueling sectarianism, dividing the country. His actions also stoked apprehensions that Shiism, with Shia Iran as the lance, would soon take over the region. Author Vali Nasr had warned of such a scenario in his 2007 book The Shia Revival: How Conflicts within Islam Will Shape the Future.

The key to the existence of ISIS lies not inside the CIA in Langley, Virginia, as some conspiracy theorists have proposed, but rather in Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, who have long feared the “rise” of Shia Islam in the region. They are the ones who have been financing their Sunni brethren within ISIS.

History was also as much a culprit as were Maliki, Bush, and Obama. The problem, which was never fixed even after Saddam’s removal, was that Iraq remains a Frankensteinian monster: a Westphalian state created in the wake of World War I that utterly failed to take regional tribal realities into consideration, a subject explored recently by Akbar Ahmed in The Thistle and the Drone: How America’s War on Terror Became a Global War on Tribal Islam. Out of the shucks of the defunct Ottoman Empire, Iraq — and several other modern states — were born, devised and delineated, not by the people involved, but rather by Western victors. Insistence on “fixing” Iraq while retaining its artificial borders compounded all the mistakes made by Bush, Obama, and Maliki, and opened the door to radicals like ISIS by creating a Sunni population that allowed their presence on Iraqi soil.

By using sovereignty as the basic unit and resisting the breaking up or redrawing of states, the modern international system thus makes it very difficult to address problems such as those that continue to plague Iraq and the Middle East.

The persistence of sectarian strife was therefore almost inevitable. The problem, however, is that the current antagonist is so virulent that action — military action — is once again necessary. ISIS is not just a new player in Iraq’s long, sad history of tribal warfare. It is genocidal and, like al-Qaeda and like-minded groups, it operates well outside the scope of Islam, warping religious scriptures to “justify” its abominable acts.

So when we see innocent civilians slaughtered by the hundreds, when men, women, and children (as well as foreign journalists) are decapitated on film, and when the scale of the mass murders (committed and planned) reaches genocidal proportions, we must support the force of arms to put an end to the horror, as should have been done in Rwanda in 1994. But doing so will take a lot more than pinprick aerial bombings; once again, we will need boots on the ground and enough firepower to eliminate ISIS as a force capable of threatening an entire society.

As always, it is to the U.S. that the international community (and the Iraqi government) will turn for such policing action, and American warplanes have already launched operations (journalist James Foley’s purported beheading seems to have been in response to U.S. bombings, and Steven Sotloff, who writes for Time and Foreign Policy, could be next).

But here’s the catch: although the U.S. should have the moral high ground, its reputation is severely undermined by Washington’s longstanding unwillingness to scold, if not rein in, its ally Israel, who just recently killed more than 2,000 Palestinians — the great majority of them innocent civilians, according to Palestinian health officials — in its latest incursion in Gaza. In many ways, several beheadings of innocent men, women and children occurred in Gaza in recent weeks, except that rather than crude knives, U.S.-made bombs and missiles, “cleanly” dropped and launched from U.S.-made warplanes, took care of the decapitations. (My aim here isn’t to draw a moral equivalence or find parallels between Israeli action and ISIS, but simply to point out the reality of the massacres in Palestinian territories, which even if sanctioned by a democracy, have an impact on what we could call the “global war of perceptions.”) With incessant war and a refusal to end the construction of illegal settlements on Palestinian land, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, along with the far-right Jewish organizations whose influence on Israeli policy continues to grow, have sabotaged the United States’ already imperfect (and certainly selective) reputation as a defender of human rights.

Of course Washington’s almost unconditional support for Israel, even when Israel descends into counterproductive excess, doesn’t stem from a cold American fascination with the dismemberment of Palestinian civilians. It is instead the result of strategic calculations (some would say miscalculation) and several other factors, including the Israeli lobby, religious beliefs, and the defense industry. Whatever the causes for that support, the relationship with Israel is severely hampering the U.S. military’s ability to do good work abroad, which in this instance involves defending millions of innocent Muslims (and minority Christians) in Iraq.

As a result, even if the U.S. is, in my opinion, fully justified this time around in intervening militarily in Iraq to help the Iraqi government and Kurdish peshmerga prevent further gains and massacres by ISIS, it is easy for cynics in Beijing, Moscow, and around the world to accuse the U.S. of double standards, of being no better than Israel — or perhaps even ISIS itself.

Not all uses of force by the Americans are intrinsically wrong or part of a “neo-colonial” project (defending Taiwan against unprovoked Chinese aggression, or interventions in Haiti, Kosovo, and Somalia, and more recently in Libya, come to mind). Force isn’t always the solution, and it should in fact be the last option. But sometimes it is necessary. Assisting Iraqis at this critical hour can be altruistic and is a necessary stopgap measure as a fragmented society tries to find a workable co-existence mechanism (moreover, Washington is partly responsible for this mess and therefore must try to fix it, which cannot be said of, say, the current crisis in Ukraine). But it’s hard to be regarded as the good guy, and to be given permission to exercise your might for a good cause, when you arm a repeat offender and give him carte blanche to commit grave injustices against an entire people, or when you are inconsistent in your defense of human rights abroad. Inconsistency poisons your good intentions not only in the eyes of your detractors, but among many of your potential allies as well.