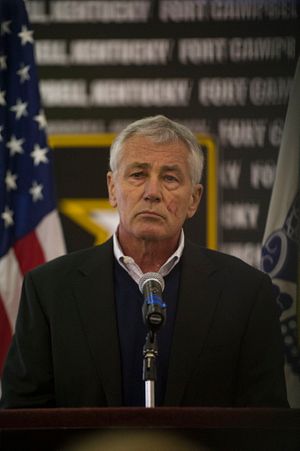

When something catches you unawares, reach for the classics to interpret it. The news of Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel’s resignation came down Monday morning during a break, and my students — as sadistic a bunch of so-and-sos as you’ll encounter — put the Naval Diplomat on the spot as to its meaning. Whereupon, having no idea what to say, I proffered… Niccolò Machiavelli!!!

The Florentine official and political philosopher is the Swiss army knife of philosophers. Look no further than The Prince, the Discourses on Livy, or The Art of War to start formulating answers to questions about statesmanship.

What can a Renaissance philosopher say about bureaucratic politics in modern-day America? Well, I have in mind a passage from the Discourses (III:9) where Machiavelli depicts staying in tune with the times as among the most vexing, most crucial challenges for rulers. Princes must adapt continually to changing “modes,” he proclaims, if they wish “always to have good fortune.” Remaining stagnant or inflexible while the world moves on threatens ill fortune.

Machiavelli has Roman history — his fount of data for the Discourses — on his mind. After the Carthaginian general Hannibal invaded over the Alps, Rome commissioned Fabius, nicknamed “the Delayer,” to postpone a final reckoning with the Carthaginian host until Rome could amass sufficient strength to win.

Fabius deserved his nickname. His legions clung to the Carthaginians, remaining nearby while refusing battle unless exceptionally favorable conditions arose — as they sometimes did. After one sharp encounter, reports Plutarch, Hannibal likened the Roman enemy to a storm. Like storm clouds, the Romans hovered overhead while turning loose the occasional cloudburst — a minor tactical clash on Roman terms — whenever the Punic army showed weakness.

But to shift metaphors, Fabius had little go-for-the-jugular instinct. When the time came for Rome to seize the offensive — when the time for delay was over — he strenuously opposed such a transition. It was foreign to his nature. Because Fabius couldn’t transcend his native caution, Romans handed over command to Scipio Africanus. The offensive-minded Scipio carried the fight across the Mediterranean Sea to Carthage — and won.

For Machiavelli the tale of Fabius, Hannibal, and Scipio represented a parable about republics’ capacity to adapt. A liberal society, in other words, can change out the people holding important posts when need be. When a Fabius reflexively opposes change, republican leaders can replace him with a Scipio Africanus better suited to the political or strategic setting. For Machiavelli, this suppleness constitutes an advantage of great worth for republics over authoritarian societies.

And Hagel? The early commentary on his exit from the Pentagon holds that the administration brought him in to manage such challenges as defense-budget cutbacks and the drawdown in Afghanistan. Things have changed in recent months with the emergence of the Islamic State. Having contradicted the official line on ISIS, goes this account of events, Hagel has fallen out of step with the times. Someone more agreeable to President Obama’s views must be found to oversee the campaign in Iraq and Syria.

So it may be that the Obama administration is trying to keep up with the times — and pass Machiavelli’s exacting test of statecraft.

Now, the Florentine never claims that changing personnel for change’s sake is good. Political leaders are far from omniscient, and they sometimes do unwise things. They might misunderstand the times — and put some capable diplomat or commander out to pasture before his time. The leadership might misinterpret the changes to the surroundings. If so, a replacement might be just as unequal as his predecessor to the rigors of the job. Even if new blood is needed, it might be the wrong new blood.

Or political leaders may set their personal interests above the republic’s. We flatter ourselves about speaking truth to power, but power often resents having truth spoken to it — and may install yes-men in place of truth-tellers. And Machiavelli, a product of Florentine intrigues, could doubtless imagine even worse possibilities.

What’s the true story behind the coming change at the Pentagon, and who comes next? Beats me. But the great Niccolò holds up a spyglass through which we can survey the transition. That’s what the classics do.