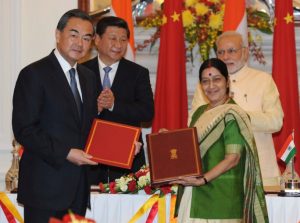

Indian Foreign Minister Sushma Swaraj’s recent articulation of the One-India Policy finally gave official expression to India’s long-held suspicion that its friendly geopolitical concessions and gestures toward the People’s Republic of China (PRC) have gone unrequited. Swaraj first communicated this thought to the visiting Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi in June. She told him that if China expects India to respect its One-China Policy, it should also reciprocate and respect the One-India Policy. Later, at a press conference on September 8, Swaraj insisted that this message was a success. If this thought can become inherent in India’s China policy, it would indeed mark a significant departure. However, the government needs to flesh out some more details for the thought to become policy. It should have a clear perspective on whether it wants to put forward the One-India Policy with respect to India’s China policy only, or if it wants to make it the general framework of a more confident foreign policy. Either option involves nuances that India will have to consider.

The belief that India should ensure the strict reciprocity of gestures and concessions in its political relations with China is not new. India has consistently maintained that China never truly appreciated India’s swift change of recognition from the Republic of China (ROC) to the PRC in 1949; its championing of China’s entry into the UN; its surrender of extra-territorial rights inherited from the British Indian government in Tibet to China; and its refusal to join the U.S. and its allies in isolating China after the Tiananmen Square episode. India in return complains that China has maintained ambiguity with regard to the Kashmir dispute between India and Pakistan, even during the heyday of the India-China friendship in the 1950s; it has propped up a nuclear Pakistan against India and essentially follows a balance of power approach towards India in South Asia, East Asia and Central Asia; and it has been less than forthcoming in supporting India in its fight against terrorism. Indians suspect that their generosity on Tibet has been in vain, as it has not resulted in India gaining any concessions from China in other border disputes. India’s insistence on reciprocity was first seen when the government of Manmohan Singh did not make the customary pledge to support Chinese authority over Tibet and its One-China policy in joint communiqués. Tibet has not figured in any joint communiqué since 2008, and the reiteration of support for the One-China policy has not appeared since 2010.

A December 4, 2011 speech delivered in Mumbai by Omar Abdullah, chief minister of Jammu and Kashmir, is perhaps the clearest public articulation by an Indian of note with regard to the One-India Policy:

I wish India shows [sic] some spine while dealing with China… we are expected to follow a ‘One China’ policy and not call into question Taiwan’s status, or not call into question Tibet’s status…Why is it that China wants us to follow ‘One China’ policy for them but it won’t follow a ‘One India’ policy for India…I think that for far too long we have been apologetic, both in terms of our relationship with Pakistan and also China which we don’t need to be. I think we should deal with China on an equal footing. If they call into question parts of our sovereignty, we have every right to call into question parts of their sovereignty.

Contrary to the PRC’s One-China Policy, the One-India Policy is still just a thought, not policy. The One-China Policy stems from China’s domestic political context – more precisely from the Chinese Civil War. The One-China Policy is not about the existing boundaries of the PRC. It is about China’s claim over Taiwan and its refusal to accept the existence of the ROC. China has pursued its One-China Policy doggedly in international politics for the last six decades. Support for the policy is a precondition for any country that might want to have diplomatic relations with the PRC; Beijing refuses to countenance any simultaneous recognition of the PRC and the ROC. And China has been successful in getting the world to accept its policy, with the exception of some 22 small Pacific Island, Latin American and African countries that still recognize the ROC as a sovereign nation. International organizations, membership of which requires statehood, are closed to Taiwan.

India has no comparable political context. It is largely content with its territory after the partition in 1947. Within the existing boundaries of the Union of India, the government’s writ is nearly ubiquitous. There are no claimants to state power outside the constitution, with the possible yet negligible exception of the ultra-leftist Maoist rebels (Naxals).

For many, Pakistan-occupied Kashmir (POK) would be a reference point for the One-India Policy, in view of the Chinese presence in the area. Both houses of Indian parliament passed a resolution in 1994 demanding that Pakistan vacate its occupied territory in Jammu and Kashmir. Yet India has made virtually no military or diplomatic effort to regain the territory either before or after the resolution.

In fact, the POK seldom figures in Indian political discourse. But if New Delhi were to use the POK as a reference point for its One-India Policy, would it do so only in its relations with China, or with other countries too? Would it object to the presence of other countries in the POK? To what extent can India make recognition of its claim on POK a pre-condition for good relations? A host of countries that deem Kashmir a dispute between India and Pakistan choose to use phrases such as “India-administered Kashmir,” and do not show the POK as part of India on their maps. What would be the implications of making POK the touchstone for the One-India Policy for India-Pakistan relations? As for Chinese claims on Indian territories, what would be the policy objective of the One-India Policy? Would India harden its position on the boundary issue? Would it shun a negotiated settlement? Would it revise its policy on Tibet and Taiwan? And, what exactly would the One-India Policy expect from the international community regarding India’s boundary dispute with China?

Another aspect of the One-India Policy could be to ensure international support for India’s fight against terrorism. In that case, the policy should be more geared toward countries to the west of India. This is where the larger international terrorist problem originates from, and where it receives most of its support. Terrorism is a fluid phenomenon and beyond government control. That India could compel the world to support its fight against terrorism on its own terms is doubtful.

These are difficult questions that will need to be resolved for this idea to graduate to a One-India Policy. A clear enunciation of the context and objectives is essential if it is to resonate within the international community. Otherwise, it will remain a vague concept, an emotional response, and a non-starter.

Dr. Prashant Kumar Singh is an Associate Fellow at the IDSA. The views expressed here at the author’s own, and do not reflect the views of the IDSA.