December 1, 2014, was the 100th anniversary of the death of Alfred Thayer Mahan, the renowned naval historian, strategist, and geopolitical theorist. It was an anniversary, unfortunately, that went largely unnoticed. Beginning in 1890 and continuing for more than two decades, Mahan, from his perch at the U.S. Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island, wrote twenty books and hundreds of articles in an effort to educate the American people and their leaders about the importance of history and geography to the study and practice of international relations. His understanding of the anarchical nature of international politics, the importance of geography to the global balance of power, the role of sea power in national security policy, and history’s ability to shed light on contemporary world politics remains relevant to the 21st century world.

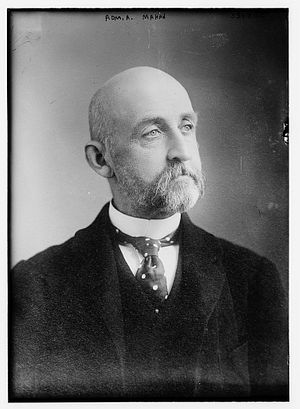

Mahan, the son of the legendary West Point instructor Dennis Hart Mahan, was born in 1840, graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1859, served in the Union Navy during the Civil War, and thereafter served on numerous ships and at several naval stations until finding his permanent home at the Naval War College. In 1883, he authored his first book, The Gulf and Inland Waters, a study of naval engagements in the Civil War. It was his second book, The Influence of Sea Power Upon History 1660-1783 (1890), however, that brought him national and international fame. The book, largely based on Mahan’s lectures at the Naval War College, became the “bible” for many navies around the world. Kaiser Wilhelm II reportedly ordered a copy of the book placed aboard every German warship.

In his memoirs, From Sail to Steam, Mahan credited his reading of Theodore Mommsen’s six-volume History of Rome for the insight that sea power was the key to global predominance. In The Influence of Sea Power Upon History, Mahan reviewed the role of sea power in the emergence and growth of the British Empire. In the book’s first chapter, he described the sea as a “great highway” and “wide common” with “well-worn trade routes” over which men pass in all directions. He identified several narrow passages or strategic “chokepoints,” the control of which contributed to Great Britain’s command of the seas. He famously listed six fundamental elements of sea power: geographical position, physical conformation, extent of territory, size of population, character of the people, and character of government. Based largely on those factors, Mahan envisioned the United States as the geopolitical successor to the British Empire.

Eight years before the Spanish-American War resulted in the United States becoming a world power with overseas possessions, Mahan wrote an article in the Atlantic Monthly entitled “The United States Looking Outward,” (1890) in which he urged U.S. leaders to recognize that our security and interests were affected by the balance of power in Europe and Asia. Mahan understood that the United States, like Great Britain, was geopolitically an island lying offshore the Eurasian landmass whose security could be threatened by a hostile power or alliance of powers that gained effective political control of the key power centers of Eurasia. He further understood that predominant Anglo-American sea power in its broadest sense was the key to ensuring the geopolitical pluralism of Eurasia. He famously wrote in The Influence of Sea Power upon the French Revolution and Empire that it was the navy of Great Britain (“those far distant storm-beaten ships”) that stood between Napoleon and the dominion of the world.

This was a profound geopolitical insight based on an understanding of the impact of geography on history. In later writings, Mahan reviewed the successive moves toward European continental hegemony by the Spanish and Austrian Hapsburgs, Louis XIV’s France, and Revolutionary and Napoleonic France, and the great coalitions, supported by sea power, that successfully thwarted those would-be hegemons.

In subsequent articles and books, Mahan accurately envisioned the geopolitical struggles of the 20th and 21st centuries. In The Interest of America in International Conditions (1910), Mahan foresaw the then-emerging First World War and the underlying geopolitical conditions leading to the Second World War, recognizing that Germany’s central position in Europe, her unrivalled industrial and military might on the continent, and her quest for sea power posed a threat to Great Britain and ultimately the United States. “A German navy, supreme by the fall of Great Britain,” he warned, “with a supreme German army able to spare readily a large expeditionary force for over-sea operations, is one of the possibilities of the future.” “The rivalry between Germany and Great Britain to-day,” he continued, “is the danger point, not only of European politics but of world politics as well.” It remained so for 35 years.

Mahan also grasped as early as 1901 the fundamental geopolitical realities of the Cold War that emerged from the ashes of the first two world wars. In The Problem of Asia, Mahan urged statesmen to “glance at the map” of Asia and note “the vast, uninterrupted mass of the Russian Empire, stretching without a break . . . from the meridian of western Asia Minor, until to the eastward it overpasses that of Japan.” He envisioned an expansionist Russia needing to be contained by an alliance of the United States, Great Britain, France, Germany, and Japan, which is precisely what happened between 1945 and 1991.

Mahan’s prescience did not end there, however. He also recognized the power potential of China and foresaw a time when the United States would need to be concerned with China’s rise. In 1893, Mahan wrote a letter to the editor of the New York Times in which he recommended U.S. annexation of Hawaii as a necessary first step to exercise control of the North Pacific. If the United States failed to act, Mahan warned, “the vast mass of China . . . may yield to one of those impulses which have in past ages buried civilization under a wave of barbaric invasion.” Should China “burst her barriers eastward,” he wrote, “it would be impossible to exaggerate the momentous issues dependent upon a firm hold of the [Hawaiian] Islands by a great civilized maritime power.”

Similarly, in The Problem of Asia, Mahan depicted a future struggle for power in the area of central Asia he called the “debatable and debated ground,” and identified the “immense latent force” of China as a potential geopolitical rival. “[I]t is scarcely desirable,” Mahan wrote, “that so vast a proportion of mankind as the Chinese constitute should be animated by but one spirit and moved as a single man.” Mahan knew that Western science and technology would at some point be globalized and wrote that under such circumstances “it is difficult to contemplate with equanimity such a vast mass as the four hundred millions of China concentrated into one effective political organization, equipped with modern appliances, and cooped within a territory already narrow for it.”

Like Germany before the First World War, China in the 21st century has embraced Mahan. Naval War College professors Toshi Yoshihara and James Holmes have examined the writings of contemporary Chinese military thinkers and strategists in this regard in their important work, Chinese Naval Strategy in the 21st Century: The Turn to Mahan. With regard to Mahan’s elements of sea power, China is situated in the heart of east-central Asia and has a lengthy sea-coast, a huge population, a growing economy, growing military and naval power, and, at least for now, a stable government. China’s political and military leaders have not hidden their desire to supplant the United States as the predominant power in the Asia-Pacific region. Under these circumstances, China’s embrace of Mahan is reason enough for Americans to reacquaint themselves with the writings of that great American strategic thinker.

Francis P. Sempa is the author of Geopolitics: From the Cold War to the 21st Century (Transaction Books) and America’s Global Role: Essays and Reviews on National Security, Geopolitics, and War (University Press of America). He has written articles and reviews on historical and foreign policy topics for Strategic Review, American Diplomacy, Joint Force Quarterly, the University Bookman, the Washington Times, the Claremont Review of Books, and other publications. He is an Assistant U.S. Attorney for the Middle District of Pennsylvania, an adjunct professor of political science at Wilkes University, and a contributing editor to American Diplomacy.