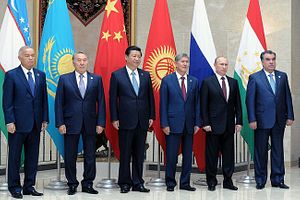

For the last few years, one of the largest questions facing Central Asia pertained to the Chinese security component in the region. Beijing’s economic hegemony, especially as it pertained to hydrocarbons, stood plain to see. Between infrastructural development and gas transit, China’s supplanted Russia as the region’s leading economic and energy pole. To choose but one statistic, Russia’s natural gas imports from Central Asia have dropped some 75 percent since their 2008 high – all while China continues bringing further transit routes online, morphing into the region’s primary export client.

Moscow, however, retained a security advantage in the region: CSTO bases, defense systems overlap, potential expansion moving forward. As the U.S. fumbled out of the region, and despite Washington’s sudden uptick in security interest, Moscow remained the primary security patron within Central Asia.

That, however, may be shifting – and we may finally be gaining a glimpse of the form China’s security extension into Central Asia is likely to take. Details remain sketchy and lightly sourced, but seem to point to a potential shift in the region’s security calculations.

According to WantChinaTimes, which cited a Canadian-based defense publication, “China plans to sell HQ-9 surface-to-air missiles to its Central Asian neighbors of Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan to reduce the price it has to pay the two countries for natural gas[.]” Local Uzbek sources backed the claim, but Beijing, Ashgabat, and Tashkent – not necessarily the most transparent regimes – have remained mum on the matter. As such, without further confirmation, the reports should be taken with a certain grain of salt.

Nonetheless, there remains enough plausibility within the reports to treat them seriously. China looks set as both Turkmenistan’s and Uzbekistan’s largest natural gas customer for the foreseeable future, with supply expansion planned over the coming years. Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, meanwhile, remain outside the Russian-led CSTO framework, with Tashkent leaving the group in 2012. On both ends, the deal makes sense, with all three governments able to point to putative threats from ISIS and Afghanistan spillover as reason enough to proceed with the arrangement.

If and when the deal comes through, Russia’s reaction will be well worth watching. It seems safe to presume that hackles in certain Moscow circles have already been raised. While significant distance remains between Moscow and the Ashgabat-Tashkent tandem, Russia retains the conventional view that the region remains within its specious sphere of influence. Indeed, recent economic rapprochement between Russia and Uzbekistan hinted at potential security rapprochement as well. But as highlighted by both the American and Chinese deals, Uzbekistan’s far from returning to Russia’s fold. All the while, China’s military advantage remains, as ever, quite real. As a recent ECFR report noted, “Russia would … be quickly defeated in a conventional border conflict with China[.]” The moves will not be seen as the most comforting from Moscow’s vantage.

While it remains to be seen how this report will play out both in Moscow and on the ground, if there’s one obvious winner, it comes in the form of Uzbek President Islam Karimov. Karimov has received external security support from both the U.S. and China in a matter of weeks – also while wringing nearly $1 billion in forgiven debt from Russia. Regional tussles remain, with Uzbekistan standing to gain at each juncture. Unlike Kazakhstan, and notwithstanding dire rumors about his health, Karimov’s 2015 has begun in fine form.