Here are some links to interesting reads you shouldn’t miss (in addition to those in our own Crossroads Asia, of course):

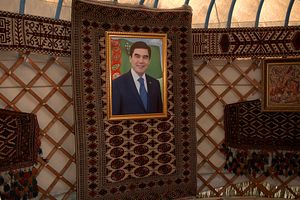

First, over on RFE/RL’s Qishloq Ovozi Bruce Pannier describes the two month wait of people living in Turkmenabat, Turkmenistan. The town had been notified that President Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov would be visiting — just not specifically when. In sadly standard Turkmen style, Berdimuhamedov has deftly paved over his predecessors cult of personality and constructed his own — including a desire for empty streets, smiling faces, and buildings devoid of satellite dishes or laundry lines. So the people of Turkmenabat, unsure of when he would show up, developed a daily routine, including street sweeping and rehearsal for a song and dance number. They found out he was finally coming on June 25, the same day he was visiting.

Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot comes immediately to mind. The play is a “tragicomedy in two acts,” which follows two men — Vladimir and Estragon — as they wait for someone named Godot. Early in the first act Estragon suddenly says to Vladimir,“Let’s go.” Vladimir says, “We can’t.” When asked why, he replies: “We’re waiting for Godot.” Despairingly, Estragon replies “Ah!” and the two continue waiting. Spoiler: they never actually meet Godot. At least, Pannier notes, “the people of Turkmenabat know their lives are finally about to return to normal” now that the president has come.

Speaking of normal, everyday occurrences, Catherine Owen wrote about a recent train trip from Bishkek to Moscow, taking note of what’s changed since the last time she made the trip four years ago. Not only does Owen describe in great detail what the three-day trip is like, she takes note of how everyday corruption has changed along the route. The train was less crowded this time — owing to cheaper international flights — and she didn’t see any border guards extorting money. Still, corruption thrives on the train in the form of unticketed stowaways and the “smuggling of illicit goods across the borders to sell at bazaars in Moscow and Samara.” Everything from shoes to yogurt was crammed into the train. My favorite part:

…boxes packed with bottles of Kyrgyz cognac were shoved under seats. When I asked one of the men whether he was planning to sell the huge box of cognac at a bazaar in Russia, he smiled and replied that they were ‘presents.’

Owen astutely points out that the customs union between Russia and Kazakhstan hasn’t dampened this illegal trade. “Either smuggling remains somehow more beneficial than legitimate routes or corrupt practices have become so ingrained in everyday behavior that institutional reforms are powerless to curb them.”

The links between Central Asia and Russia run deep. Chris Rickleton wrote this week about how the past is becoming divisive in Kyrgyzstan:

In the summer of 1916, Kyrgyz nomads rose up against a World War I-era conscription drive imposed by Tsar Nicholas II’s government. When Cossacks loyal to the tsar put down the rebellion, thousands of Kyrgyz undertook a fateful exodus over snowy passes to China. Local historians claim the resistance and the “Great Flight” – or “Urkun,” as it is known in Kyrgyz – left over 100,000 Kyrgyz dead.

As the centennial approaches, President Almazbek Atambayev, regarded as pro-Russian, chose his words carefully in a May decree on the anniversary, saying that “massive unrest in Kyrgyzstan took on the character of a rebellion not against the Russian people, but against tsarist colonialism.” While Kyrgyzstan largely remains pro-Russia, Rickleton writes, “1916 has become a political football in parliament,” featuring nationalists and those opposed to Kyrgyzstan joining the EEU, and Kyrgyz pushing back on the “perceptions it is again becoming a Russian colony.”