In a revealing move, Taliban leader Mullah Omar, in his annual Eid message, declared as “legitimate” peace talks aimed at bringing to a close Afghanistan’s lengthy war. This represented the first comments the reclusive leader has made on the nascent process. Direct talks between the Afghan government and the Taliban on July 7 in Pakistan marked a major step forward after months, even years, of “talks about talks.” The talks were hailed by the National Unity Government (NUG) as “the start of the first ever official peace talks,” while Pakistan’s Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif declared the meeting a “breakthrough.” International reactions were also universally positive. At the same time, all noted that this was only the start of a long and difficult process.

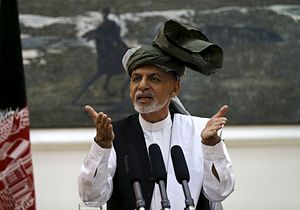

Certain positives can be drawn from the meeting. First, the fact it even took place after years of failed attempts is of considerable symbolic importance and could mark the starting point of an official peace process. While the meeting itself produced few concrete results, it was reportedly held in a “warm” and “positive” manner. For an embattled Afghan president facing a worsening security situation and a prolonged failure to appoint a new defense minister following the rejection of acting minister Mohammed Masoom Stanekzai by parliament, any sign of progress in the peace process is timely and welcome. Significantly, it provides some vindication for Ghani of his policy of outreach to Pakistan, which has been the subject of strong domestic criticism.

Participants at the meeting were also largely representative of both sides. The Afghan delegation, headed by Deputy Foreign Minister Hekmat Karzai, included figures close to Ghani, Chief Executive Abdullah Abdullah, First Vice President Abdul Rashid Dostum, Deputy Chief Executive Mohammad Mohaqeq, and Second Vice President Sarwar Danish. This suggested that there was support across the NUG for participating in the meeting. The Taliban delegation (as far as can be confirmed), headed by former Deputy Foreign Minister Mullah Abdul Jalil, was high-level and included most major factions as well as Mullah Yahya, a representative of the Haqqani Network. The most important outcome of the talks was the agreement to continue with discussions after Ramadan, likely mid-August, in China or perhaps Qatar. At a press conference, Hekmat Karzai indicated that this would focus on both sides outlining conditions and concerns that would need to be addressed during the negotiations. Although this runs the risk of derailing the process, it indicates that some form of official dialogue has begun.

Concerted Efforts

Even in the most positive scenario, it will likely take a long time to reach a mutually acceptable compromise. Concerted efforts will need to be made by both sides to ensure they can prevent skeptics from breaking away. Increasing divisions could cause the fragile peace effort to disintegrate. One day after the talks, a statement briefly appeared on the Taliban’s Voice of Jihad website denouncing the Islamabad meeting as a Pakistani ploy, and warning of catastrophic consequences. This underscored the potentially dangerous fault lines within the movement. The statement quickly vanished without explanation, while Mullah Omar’s Eid message sought to dispel any notion of a split, which suggests that the pro-peace talks’ faction has the upper hand – for now at least. Key Taliban leaders appear to be under sufficient pressure – including from Pakistan – that they feel obliged to take part in peace talks, but there are still clearly significant numbers of Taliban fighters opposed to any form of negotiation.

Among them is military commander Abdul Qayum Zakir (the former head of the Taliban’s military commission), who has reportedly been sacked (for a second time) from the military commission. Even from a weakened position, Zakir is an influential commander with a significant following among the rank-and-file, making him a potential spoiler. Additionally, while the extent of Islamic State’s presence in Afghanistan is difficult to gauge, the ISIS brand offers an alternative for disaffected Taliban leaders and their followers who oppose peace talks. The fact that there are increasing signs that Islamic State money is being channeled into Afghanistan to enable the group to expand their influence means the ISIS factor cannot be ignored, not least by the Taliban leadership.

Beyond these internal debates, the fact that the Taliban’s negotiating position does not appear to have changed in any significant way is also grounds for concern. The Taliban remains committed to continuing their military campaign in order to strengthen its negotiating position and to avoid the risk of a full-scale rupture in its ranks that any major steps in the direction of peace – such as agreeing to a ceasefire – could entail. The Afghan government was unsuccessful in getting the Taliban to commit to a ceasefire for the Eid holiday (possibly reflecting the limits of the political leadership to control the actions of fighters on the ground). The Taliban also voiced longstanding demands that foreign military forces leave Afghanistan, UN sanctions be lifted, Taliban prisoners freed, and the Afghan Constitution amended. While Hekmat Karzai told reporters that there were no preconditions to talks, statements by Ghani and other NUG leaders continue to suggest that most of these demands are still unacceptable, underscoring the intractable problems that still divide the two sides, and the real risk that negotiations could quickly break down.

This prospect is even more likely given that the Taliban’s fragmentation is mirrored to some degree on the Afghan side, with key members of the NUG and many former mujahedeen commanders opposed to negotiating with the Taliban and deeply suspicious of Pakistan. While the Afghan delegation was broadly representative of the NUG, it is still not clear that it could actually agree on common negotiating positions should talks begin to advance. The role of the former mujahedeen in blocking Stanekzai’s confirmation as defense minister demonstrates their ability to act as spoilers in any process, a position that could be strengthened by other powerbrokers who benefit from the current system and stand to lose if the Taliban is brought into government.

As such, the talks are unlikely to improve the security situation in the near term and it is too early to use words like “milestone” or “breakthrough.” Peace negotiations will be prolonged and are unlikely to influence the course of this fighting season, particularly with the increased fragmentation amongst Taliban fighters. Politically, this apparent success could bolster Ghani and, if there is continued progress, could help convince more Afghans that Pakistan has finally changed its policies. While the meeting marks a serious step in the right direction, spoilers – such as Zakir or Afghan powerbrokers, the emergence of ISIS, escalating violence, and the unpredictability of Pakistan – could cause the process to collapse. Whether a sustainable Afghan peace process is unfolding will become clearer in the coming months.

Emily Winterbotham is a Research Fellow in the International Security Studies Department at RUSI. For the past six years she has worked in Afghanistan and Pakistan, most recently as Political Adviser for the European Union Special Representative, focusing on the Afghan peace process, violent extremism and insurgent networks in South Asia.