With the light at the end of the TPP tunnel now in sight, the focus is once again on how exactly the Trans-Pacific Partnership agreement will create winners and losers within each of the 12 member countries, including Japan. But not only is there greater reconciliation about the inevitable changes that the trade pact will bring about, the hopes for what new opportunities the deal could bring are also palpable. Expectations of a new dawn for the Japanese economy are on the rise.

One question that has yet to be seriously addressed is whether Tokyo has the will and the way to provide economic leadership in a rapidly changing Asia-Pacific region amid the growing influence of China. There is undoubtedly an economic power vacuum in the region that Beijing is eager to fill, but at the same time, there is ever-growing concern among Asian nations about China’s ambitions. And trade is just one aspect of a larger picture.

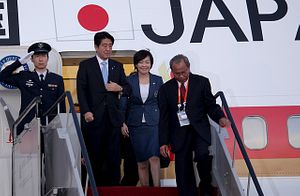

As the second-largest founding member nation of the TPP, Tokyo has a distinct advantage in setting the future rules for trade in the world’s most economically robust region. Just as U.S. President Barack Obama stressed the need for the United States to be a key player in the TPP framework lest Beijing take over instead, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe also emphasized the need for TPP to keep Japan as a major economic player on the global stage.

But when Abe announced Japan’s decision to join the TPP in March 2013, he also stated that “creating new rules in the Asia-Pacific region …is not only in Japan’s national interests, but also certain to bring prosperity to the world,” adding that “the new economic order” would be made jointly by the two major economic powers, namely Japan and the United States.

Yet over the past two years, there is growing concern that China has been taking over from Tokyo and Washington as the rule-maker for Asia. For while the TPP is undoubtedly the most ambitious and comprehensive global trade regime to date, there are also alternative frameworks in the works, including the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) agreement and the Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific (FTAAP), not to mention the trilateral China-Japan-Korea trade talks, all of which involve Beijing.

At the same time, China has come up with a number of ambitious economic development plans that underpin its One Belt One Road initiative. The most notable of those strategies is the launch of the Asian Infrastructure Development Bank, for which the official signing ceremony of the founding 50 member countries was held in the Chinese capital last week. The AIIB initiative has been an unexpected success for Beijing, having attracted not only the more obvious possible beneficiaries of low-interest loans, but also major donor nations both within and outside of the region, including Australia, South Korea, Britain, France, and Germany. In fact, the two most notable non-members have been Japan and the United States.

Yet there has been a rapid change in the AIIB lineup too, as seven countries that signed the initial Memorandum of Understanding – Philippines, Thailand, Malaysia, Denmark, Kuwait, Poland, and South Africa – chose not to join on the date of establishment, with the Philippines at least swayed by territorial disputes in the South China Sea.

Clearly, there is a need for further funding for infrastructure projects across the region, but Southeast Asia and much of the world at large are clearly apprehensive about China’s broader ambitions. There is, in short, an opportunity for Japan to step up to the plate and provide an alternative to Chinese-led initiatives.

Japanese policymakers remain divided on whether Tokyo should join the AIIB, but some have urged the Abe government to break away from Washington’s rejection of the bank and sign on for political reasons. That rallying cry to join the new institution comes despite efforts to boost the infrastructure lending capabilities of the rival Manila-based Asian Development Bank, which has traditionally been led by a Japanese national. The AIIB will be the first real test for Beijing to see whether it can develop a financial institution that competes head-on with those that had been created in the 20th century, and which adheres to global standards of lending and governance at the same time. The bank’s success could in turn herald a new dawn for China in setting broader economic rules for a rapidly evolving region, where needs are clearly not being adequately met by existing frameworks.

The opportunity for Japan to provide an alternative economic vision to China certainly exists, and amid concerns about China’s territorial ambitions coupled with its rapid military growth, the need for greater Japanese leadership in the region continues to grow. Nevertheless, Tokyo has yet to come up with a regional initiative like it did during the 1997 Asian financial crisis when it put forward its proposal for an Asian Monetary Fund. That plan resonated at a time when there was deep ambivalence toward the International Monetary Fund and its conditionality for bailout loans. But one senior Japanese official argued that the AMF proposal was quickly rejected by the United States, much like the AIIB faced steep opposition from Washington. But unlike China, Japan let expectations for the AMF die out.

Looking ahead, there are two looming questions for Tokyo: Can Japan come up with an alternative vision for continued growth across Asia, and can it press forward with that vision even if it does not have Washington’s full support? Given that, for both economic and political reasons, the United States has no intention of joining the AIIB, the first test for Japan may well be whether or not it elects to join the AIIB as the need for alternative systems to ensure steady growth across Asia continues to rise.

Shihoko Goto is the senior associate for Northeast Asia with the Woodrow Wilson Center’s Asia Program based in Washington D.C.