In 1975, the Vietnam War ended with the United States’ political defeat to the communists. Forty years later, if nothing changes, from 6-7 July the highest-ranking official of the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV) will visit Washington, D.C. for the first time. Though there have been disagreements about protocol procedures – General Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong has no direct counterpart from the United States – the trip is unquestionably historic one as it comes as both countries celebrate the 20th anniversary of their normalized relationship.

The trip will strengthen the two countries’ bilateral communication and political contacts at a critical time. Both are members of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), an agreement which will hopefully be wrapped up before U.S. President Barack Obama leaves office. Maritime tensions stemming from China’s reclamation projects and militarization of artificial islands in the South China Sea also continue to undermine regional peace and stability. But beyond these specific issues, the meeting itself will be symbolic of a transition to a new phase in U.S.-Vietnam relations.

In 1994, the United States finally lifted its trade embargo on Vietnam, marking a new era for U.S-Vietnam normalization. Beyond memories about the bloody Vietnam War, since then the U.S-Vietnam relations have been transforming from enmity to a “comprehensive partnership” through an array of cooperative efforts in the fields of security and trade. The early twenty first century has witnessed the rise of China both militarily and economically, which undeniably plays a catalytic role in this metamorphosis.

In 2000, both countries signed the Bilateral Trade Agreement (BTA), which served as a stepping stone to Vietnam’s accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2007. The BTA gave Vietnam preferential access to the U.S markets by reducing tariff rates on Vietnam’s imports to the world largest economy, while Vietnam’s membership in WTO expedited its economic integration into the global market. Against the backdrop of the aging and increased wage rates of Chinese blue-collar segments, Vietnam’s younger and cheaper labor has been an attractive alternative that could help the American economy become less dependent on China’s imports, which are partly responsible for the growing U.S.-China trade imbalance.

Almost twenty years since the normalization of U.S-Vietnam trade relations, their economic partnership has made remarkable progress. Last Wednesday, the Republican-led Senate passed legislation granting president Obama the authority to fast track negotiation process of the TPP. The trade agreement will not only benefit both the United States and Vietnam according to their economic comparative advantages, but will also play an important part of their soft balancing strategies against China.

The increasing influx of U.S textile imports to Vietnam would render the domestic garment industry less reliant on China’s textile imports for production. That is important because Vietnam’s heavy economic dependency on China can be exploited for Beijing’s political leverage on Hanoi. Additionally, the TPP would permit U.S multinational footwear firms such as Nike to outsource their jobs to Vietnam, where production costs would be significantly reduced when U.S tariffs on garments and shoes made in Vietnam could go from 7 percent and 32 percent respectively to zero. In return, the TPP would allow Vietnam’s garment producers to gain preferential access to the U.S textile market, which accounts for a quarter of a million American jobs. In a time of growing economic interdependence, the United States can utilize its economic power through the TPP to build up its legitimacy and challenge China’s regional leadership in the Asia-Pacific due to its exclusion from the trade pact.

With respect to security, China’s increasing military modernization poses a threat to both countries’ national security, especially Vietnam due to her geographical proximity to China. The United States and Vietnam share similar interests in hedging against China’s coercive resolutions to the South China Sea disputes. Despite the United States’ neutrality on the territorial disputes, it views China’s ownership claims as a big threat toward the freedom of navigation and international trade-flows in Asia-Pacific waters. On the other hand, the CPV has espoused soft balancing strategies through indirect means by increasing American regional engagement. Unsurprisingly, China’s dispatch of a massive oil rig to Vietnam’s claimed exclusive economic zone (EEZ) in 2014 has pushed Vietnam much closer to the United States. Hanoi sees Washington as the country it can rely on to build up its defense capabilities if the Russians bail out.

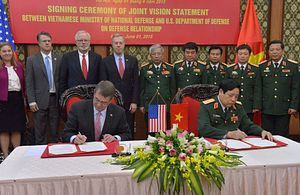

Any comprehensive analysis of the current dynamics of U.S-Vietnam defense ties would be incomplete without mentioning the Joint Vision Statement which Defense Secretary Aston Carter and his Vietnamese counterpart Phung Quang Thanh inked in May. The non-binding statement is an extension of the Memorandum of Understanding for Advancing Bilateral Defense Cooperation, signed by the two parties back in 2011. Following Washington’s decision to partially remove its restrictions on sales of lethal weapons to Vietnam in October 2013, the statement aims to expand “the defense trade” between the two nations and set up the stage for introducing a bill further lowering the bar on arm sales. It also includes the option of co-manufacturing of military equipment and the “navigation of complex U.S procurement rules.” This is a win-win for both sides. From the perspective of the CPV, the statement could tremendously reduce Vietnam’s dependence on Russian military suppliers for its defense needs. From the Washington’s perspective, this can provide the U.S defense industry with greater access to an emerging Asian market while diminishing Russia’s global military influence.

“Not antagonizing China” is an important component of the rebalancing strategy, if not the immutable bedrock of gradual institutionalization of U.S-Vietnam security and trade cooperation. The United States and Vietnam are willing to increase personnel exchanges, develop economic and trade relations, conduct joint military programs, and raise criticisms against China’s revisionism to the extent that these measures do not jeopardize their relationships with Beijing. For this reason, the Vietnamese government announced its adherence to the “Three No” principles in national defense and diplomacy, including no military alliances, no alliances with any country in conflict with another and no acceptance for foreign countries’ building of military bases on Vietnam’s territory. On the other hand, the United States does not wish the deepening of U.S-Vietnam military ties to come at the expense of declining Sino-U.S. trade relations.

Human rights issues still remain the biggest impediment to the U.S-Vietnam relations in the coming years. Yet, successful nation-building stories in Asia have demonstrated that marketization usually predates political reforms in development of states. After all, Vietnam is still at an early stage in its developmental process. From the Vietnamese government’s point of view, human rights is still a foreign concept. Any major breakthrough by Hanoi when it comes to internalizing international human rights norms into domestic practices depends on the speed at which these values become congruent with preexisting political and societal institutions in Vietnam. The good news is that recent years have seen major improvements in economic and social rights thanks to Vietnam’s rapid socioeconomic development after economic reform. From Washington’s standpoint, there is plenty of room for improvement in human rights conditions, and the country will rely on its young generation to take up the challenge, as U.S Senator McCain said during his speech at Ho Chi Minh University of Social Sciences and Humanities.

The U.S and Vietnamese governments admit the inevitability of their ideological and political differences. However, the general consensus is that further collaborative efforts – particularly in the economic realm – are essential for further narrowing the chasms between the former foes and completing the transformation that is already underway in U.S.-Vietnam relations.

Cuong T. Nguyen is a graduate from the Committee on International Relations (CIR) at the University of Chicago, and currently a research fellow of Saigon Center for International Studies (SCIS) at the University of Social Sciences and Humanities in Ho Chi Minh City.