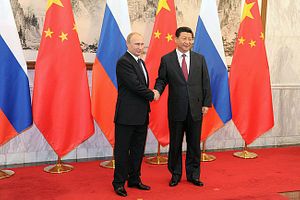

On May 8, 2015, the Russian Federation and the People’s Republic of China signed a bilateral agreement on cooperation in the field of international information security. The treaty, which some have dubbed a “nonaggression pact” for cyberspace, details cooperative measures both governments pledge to undertake, including exchange of information and increased scientific and academic cooperation. With this, Russia and China continue to advance their vision of “information security,” a view of security concerns in cyberspace that is markedly differentfrom Western approaches of “cybersecurity.”

Many observers have characterized the agreement as a largely political move at a time of heightened tensions with the United States and Europe. The alignment of Russia and China is seen as a response to growing Western pressure. Accordingly, Russia’s pivot to the East follows Western sanctions over its actions in Ukraine.

However, a closer look reveals that the agreement follows a longstanding series of diplomatic initiatives launched by both countries. Already in 2009 Russia and China signed an agreement on cooperation in the field of international information security in the framework of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Later, in 2011 both countries submitted a proposal for an international code of conduct for information securityto the United Nations. Although the proposal failed to garner sufficient support in the relevant Committee of the General Assembly, Russia and China redoubled their efforts. Anupdated version of the code of conduct is currently circulating in the UN in time for this fall’s General Assembly session. All these initiatives sought to advance Russia’s and China’s views on a variety of cybersecurity issues while shoring up their positions in international discussions. This year’s bilateral agreement is no exception in this regard.

Familiar Themes

The treaty picks up on many of the themes from past documents. For one, the Russian-Chinese agreement continues to define “threats” in cyberspace broadly. While the treaty mentions threats that would also be of concern to the United States and Europe, the pact also defines cyber threats as the transmission of information that could endanger the “societal-political and social-economic systems, and spiritual, moral and cultural environment of states.” Obviously, this could be interpreted very broadly and Western countries have been concerned that similar provisions could be used to unduly restrict the free flow of information.

Second, the agreement between Russia and China also touches upon questions of Internet governance. Continuing previous efforts, the document calls for the creation of a “multilateral, democratic and transparent management system” for the Internet, giving states and their governments a greater, if not predominant, voice in the governance process. This view of multilateral Internet governance stands in contrast to the multi-stakeholder model preferred by Western states.

Novel Aspects

The treaty is most interesting for its novel aspects. Compared with past initiatives, the agreement details a remarkable level of cooperation. Whereas previous pledges of cooperation remained vague and somewhat aspirational, the current agreement provides a list of concrete measures and policies to be realized by both sides, coordinated and evaluated through two consultation meetings a year. These range from the creation of contact points and communication channels between various government entities to the realization of joint scientific projects.

Moreover, the agreement stands out for its normative aspects. It specifically provides that both countries shall cooperate in the creation and dissemination of international legal norms in cyberspace. This includes increased cooperation and coordination of positions in various international forums, including the UN, where both countries have been pushing for the negotiation of new international legal norms to regulate the use of cyber warfare. The agreement thus formalizes their joint interest in shaping the international debate on norms in cyberspace.

Lastly, one provision has been widely reported as a “nonaggression” provision whereby Russia and China, for the first time, pledge to refrain from “computer attacks” against each other. In Article 4 the treaty provides that:

Each Party has an equal right to the protection of the information resources of their state against misuse and unsanctioned interference, including computer attacks against them. Each Party shall not exercise such actions with respect to the other Party and shall assist the other Party in the realization of said right.

The two sentences, in conjunction, could be read in a way to keep Russia and China from using “computer attacks” against each other. If so, this provision would be remarkable not only for its content but also for the kind of language it employs. Previously, particularly China has avoided the usage of language that could implicate the right to self-defense, which it interprets as legitimizing the use of offensive cyber activity in conflict.

On the other hand, the language of this provision is strikingly vague. Phrases such as “misuse” and “unsanctioned interference” could obviously be interpreted quite differently by both sides leaving significant loopholes in the scope of the provision. Given the magnitude of Russian and Chinese activities in cyberspace, including those directed against each other, this commitment and the seriousness with which it will be implemented are questionable. Thus, the characterization of this provision as a “nonaggression” pledge might be overstated.

Implementation Will Be Critical

Overall, the Russian and Chinese agreement continues many familiar themes. It echoes previous diplomatic initiatives that have united both countries in international cybersecurity discussions. Yet, it also offers a number of novel aspects.

In the end, however, the treaty itself is just the first step. The decisive aspect in evaluating the impact of this document will be its implementation. Particularly the implementation (or non-implementation) of the cooperation commitments, and even more so of the “nonaggression” provision, will decide whether the agreement really marks the beginning of a closer relationship between both countries or whether it will be relegated to a symbolic diplomatic effort overtaken by reality.

Elaine Korzak, PhD is a W. Glenn Campbell and Rita Ricardo-Campbell National Fellow at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University, and an Affiliate at the Center for International Security and Cooperation (CISAC), Stanford University. This post appears courtesy of CFR.org.