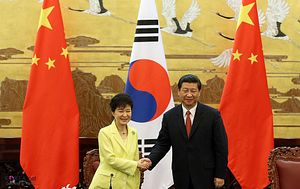

When South Korean President Park Geun-hye met with Chinese President Xi Jinping on Wednesday, a day before the two watched China’s military parade sitting nearly side-by-side, the two leaders painted a rosy picture of China-South Korean cooperation. But a recent slowdown in China’s economy also underlines the perils of such close ties.

South Korea’s most important economic relationship is with China. The condition of this relationship will largely determine the health and well being of the ROK economy — and things are not looking promising.

The Financial Times reported earlier this week what those familiar with South Korea’s asymmetric trading relationship with China knew was coming: an export plunge. “Exports fell 14.7 per cent last month from a year before … the biggest decline since August 2009.” While smartphone and semiconductor exports rose, petroleum products and ships took the deepest dive at 40.3 percent and 51.5 percent, respectively. With further declines in exports predicted, coupled with the recent devaluation of the renminbi, some expect the Bank of Korea to cut the interest rate from an already record low rate of 1.5 percent. A weak renminbi will only further decrease China’s spending power, meaning an even further drop in exports for Korea. A race to the bottom, as it were.

The current export woes go to show just how dependent South Korea’s economy is on shipping goods abroad. An export-oriented economy, South Korea is this way by design. South Korea’s developmental state deliberately fostered export-focused conglomerates, called chaebols. Samsung, LG, and Hyuandai are not free market accidents.

But an unintended consequence of export-oriented growth is global market volatility. When transportation costs soar, which happens with a surge in oil prices, or when global demand for Korean exports suddenly dips, the South Korean economy is hit harder than less export-dependent economies.

Between 2010 and 2014, exports averaged 53.2 percent of South Korea’s GDP, according to World Bank data. This is comparatively high. South Korea also has a relatively high trade-to-GDP ratio. The trade-to-GDP ratio is a good indicator of just how open (re: vulnerable) countries are to the dips and dives of the global economy. This statistic is calculated by adding total imports plus total exports divided by GDP in current prices. According to data from the World Trade Organization (WTO), in 2014 South Korea had a trade to GDP ratio of 103.2. Economies of comparable size have ratios between 55-65. Japan has a ratio of 33.6.

A closer look at the WTO data shows that South Korea doesn’t trade evenly. South Korea’s main trading partner is China; it is not a balanced relationship. The breakdown in the ROK economy’s total exports shows that China takes in 26.1 percent of South Korea’s exports. By imports to South Korea, China is number one, too, at 16.1 percent. By contrast, data for China shows that South Korea, while a leading trading partner, is nowhere near as crucial. In other word, China is not as dependent on South Korea as South Korea is on it. The ROK takes in 4.1 percent of China’s exports and provides 9.4 percent of China’s total imports. The China-South Korea economic relationship is a case-in-point in trading asymmetry.

The future of China’s economy may be in question. What we do know with certainty, however, is that wherever China goes, so too will South Korea. Until the ROK improves its domestic services industries (such as, perhaps, financial technology services) it will remain acutely vulnerable to external shocks. For the time being, industry exporters will likely seek ways to maintain profit margins, especially Korea’s small and medium-sized enterprises. Implications abound for chaebol reform and the labor market. As if young people didn’t already have enough to worry about.