China’s official government reactions to the recent U.S. Navy “freedom of navigation” (FON) operation within 12 nautical miles (nm) of a Chinese-occupied constructed island in the South China Sea are a multilingual puzzle. A careful examination of Chinese-language versions of Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Defense Ministry statements, however, reveals extreme subtlety in wording and an apparently coordinated effort to maintain strategic ambiguity on key questions about China’s position.

Do Chinese officials believe the U.S. Navy violated Chinese sovereignty? Unclear. Do they claim maritime rights surrounding constructed islands that go farther than the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) provides? Not explicitly. Will they specify exactly why the U.S. action is described as illegal? Not quite—but the door just cracked open.

Chinese official statements have been almost flawless in keeping these questions unanswered, with one exception discussed below. Doing so required a change in language between earlier statements warning against FON operations and this week’s protests following the event itself. In May, Ministry of Foreign Affairs Spokesperson Hua Chunying warned the United States against “violation (qīnfàn) of China’s sovereignty and threat (wēihài) to China’s national security.” Earlier this month, Hua opposed “infringement (qīnfàn) of China’s territorial sea (lǐnghǎi) and airspace (lǐngkōng).”

The use of the legally specific term “territorial sea” and the word qīnfàn (translated as “violation” or “infringement”—and a term used in such contexts as Japan’s so-called “nationalization” of the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands) set the Chinese government up for a test. In general, only features that, before any construction, sat above water at high tide can produce a 12 nm territorial sea under UNCLOS. If the U.S. Navy entered within 12 nm of a constructed island (a term I use for former low-tide elevations or former submerged features), and the Chinese government spoke of “territorial sea” or complained of qīnfàn of sovereignty, China would be making an implicit claim not well supported by UNCLOS.

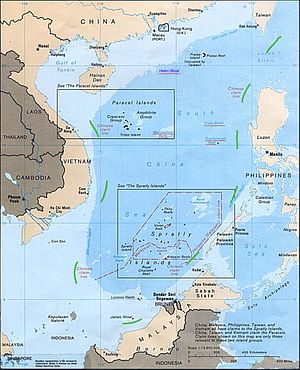

In fact, the U.S. mission was evidently designed to administer that very test by entering within 12 nm of the installation built atop Subi Reef, which is widely recognized as having originally been above water only at low tide. Would Chinese officials take the bait?

The Chinese government’s first detailed response came from Ministry of Foreign Affairs Spokesperson Lu Kang. Lu asserted that the U.S. ship had “illegally entered waters near” features in the South China Sea. For “waters near” he did not use the Chinese term for territorial sea, but instead referred to línjìn hǎiyù, literally “nearby” or “neighboring” waters. Lu said the U.S. activity “threatened (wēixié) China’s sovereignty and security interests,” but he did not say those interests were violated or infringed. Later in the statement, Lu asserted Chinese sovereignty over the “Nansha Islands and their adjacent waters (fùjìn hǎiyù),” pointedly using a different Chinese term from the one the U.S. was said to have entered.

Finally, modifying Hua’s earlier warning against using FON as an excuse to “violate” sovereignty, Lu said China opposes using FON as an excuse to “harm (sǔnhài)… China’s sovereignty and security interests.” Lu finally urged the United States to refrain from actions “detrimental to (wēixié) China’s sovereignty and security interests,” returning to the verb used to describe what Lu had accused the U.S. Navy of doing that day.

In this statement, Lu avoids taking an explicit or implied position on: whether Subi Reef can produce a 12 nm territorial sea, whether the U.S. Navy violated Chinese sovereignty, what specific maritime areas China claims sovereignty over, and what if any escalation thresholds may exist in any future encounters. Quite a feat—and one repeated by Vice Foreign Minister Zhang Yesui, according to a readout of his meeting with U.S. Ambassador Max Baucus.

But we’re not done. Around the same time, Defense Ministry Spokesperson Yang Yujun made his own statement. Yang also avoided the term “territorial sea” (lǐnghǎi) throughout, instead using “offshore waters” (jìnàn shǔiyù) and “adjacent waters” (fùjìn hǎiyù). Yang avoided calling the U.S. action illegal, but called it an abuse (lànyòng) of freedoms of navigation provided for in international law. Yang declared the U.S. action a serious threat (yánzhòng wēixié) to China’s national security (though not necessarily to sovereignty), and he urged the United States to respect China’s concerns about sovereignty and national security.

By avoiding the term “territorial sea” and any explicit statement about the basis for calling the U.S. action illegal, officials for the most part maintained China’s carefully cultivated ambiguity about the nature of Chinese claims in the South China Sea. By doing so, they deny U.S. planners one of their most likely goals in conducting FON operations, to force reluctant Chinese officials to put forth claims that are unlikely to find support in international law.

Some ambiguity, however, has been surrendered. On October 28, Lu declared, “What the U.S. has done violates (wéifǎn) the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea as well as relevant domestic law of China.” If future statements confirm a Chinese view that the U.S. action violated UNCLOS, the U.S. government will have very legitimate questions. What kind of jurisdiction does China’s government claim in which waters? Does China assert a territorial sea surrounding Subi Reef? If so, how did the ship violate the rules of innocent passage, as set out in UNCLOS? Alternately, does China assert an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) in the South China Sea? If so, what are its boundaries, and what does China allege the U.S. ship did to violate the permissive UNCLOS regime on military activities in EEZs?

International law evolves through precedent and state practice, and there are legitimate scholarly and diplomatic disagreements on how to apply UNCLOS. For now, however, careful Chinese officials have denied opponents specific grounds on which to argue.

Graham Webster (@gwbstr) is a researcher, lecturer, and senior fellow of The China Center at Yale Law School. Sign up for his free e-mail brief, U.S.–China Week.