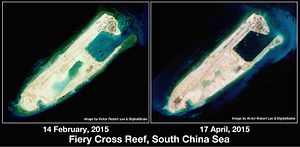

Much has been said about the legal and geopolitical aspects of Chinese land reclamation in the South China Sea, but U.S. PACOM Commander Admiral Harry Harris’s Congressional testimony last month gave a closer look at specific U.S. military concerns posed by China’s artificial islands. Harris detailed the military utility of deep water port facilities and 3,000 meter runways on three newly built Chinese islands, while Assistant Secretary of Defense for Asian and Pacific Security Affairs David Shear noted the threat that “higher end military upgrades, such as permanent basing of combat aviation regiments or placement of surface-to-air, anti-ship, and ballistic missile systems on reclaimed features” might pose.

What exactly is the nature of the potential Chinese military threat, and what implications does it have for the region?

What Might A Chinese Military Threat Look Like?

Each of the above military concerns merit further examination in spite of China’s vehement declarations that its new islands are for civilian purposes. China has a range of militarization options for its new South China Sea facilities, ranging from deploying intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) assets, to missile batteries, to augmenting power projection capabilities, each with its own particular costs, benefits, and escalatory severity.

Deploying ISR assets to reclaimed land formations would significantly enhance Chinese situational awareness in the contested region. A long-range surveillance radar could detect ships and aircraft up to 320 km away from Chinese-occupied features in the South China Sea. Chinese Y-8X maritime patrol aircraft launching from a 3,000 meter runway on Fiery Cross Reef would be able to locate and track ships and aircraft operating up to 1,600 km away, putting most of Vietnam, Malaysia, and the Philippines within range of Chinese surveillance aircraft. While neither of these steps would overtly threaten other military forces, intelligence gathered by these systems could easily be used for targeting purposes.

Chinese missile systems deployed to reclaimed land formations would tangibly increase the risk and cost of military operations by other states, posing a much more concrete military threat to both regional claimants and the United States in the South China Sea. The Chinese military has expended considerable effort over the last 20 years to strengthen its missile capabilities, and is now deploying formidable surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) and anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCMs) in large numbers in its army, navy, and air force. SAMs such as the HQ-9 and S-300 PMU-1 can destroy aircraft at ranges of 150-200km, and ground-launched YJ-62 and YJ-83 ASCMs could render large swaths of the South China Sea vulnerable to accurate, destructive fire up to 120-400km away from Chinese-occupied land formations. These missile threats would force regional powers to think twice about operating ships or aircraft in the region against Beijing’s wishes.

At the most costly end of the spectrum, China could use its newly reclaimed islands to augment its power projection capabilities throughout the region. Airstrips and deep water ports on Fiery Cross and Mischief Reefs could serve as diversion and resupply points for Chinese military ships and aircraft that otherwise wouldn’t have the range to operate safely in the South China Sea. Basing aerial refueling tankers on these land features could materially extend the range of Chinese military aircraft patrolling in the region, while basing H-6K strategic bombers would put countries as far as Australia within striking distance of the Chinese air force. Regularly basing military assets upon Fiery Cross and Mischief Reefs would be expensive and logistically challenging but would confer tangible benefits to a Chinese military still honing its power projection capability.

The Impact of Chinese Militarization

The nature and type of Chinese militarization would visibly illustrate China relative military superiority over other South China Sea claimants. Rival claimant states possess neither the advanced standoff strike capability nor the robust ISR assets required to challenge a hypothetical Chinese missile buildup on its new islands. The Vietnamese Navy’s most capable anti-ship cruise missile has a maximum range of 300km – still within the 280-400km range of a land-based Chinese YJ-62. Air-launched air-to-surface missiles such as the U.S.-supplied AGM-84 Harpoon would be similarly outranged by Chinese anti-aircraft systems, forcing non-stealthy aircraft to fire their missiles well inside the kill radius of Chinese S-300 series SAMs.

More importantly, even if regional military planners had standoff range missiles at their disposal, their utility would be hindered by a lack of survivable and persistent ISR assets to provide targeting information. Malaysia’s handful of Beech 200 maritime patrol aircraft and RF-5E Tigereye reconnaissance fighters are the most capable ISR platforms in the area, but these would prove easy targets for even rudimentary Chinese air defenses, to say nothing of advanced HQ-9 and S-300 series SAMs. Vietnam’s improved Kilo-class submarines could safely strike Chinese positions with 300km-range 3M14E Klub land attack cruise missiles, but counterforce accuracy would be suspect without sufficient ISR for targeting. In short, no claimant state has the operational maritime awareness and the standoff munitions needed to attack hypothetical Chinese defenses without putting the launching aircraft, surface ships, and personnel at risk from Chinese SAMs and ASCMs.

Two of the three hypothetical Chinese militarization paths appear to be comparatively cost-effective. Building islands from coral reefs and paving runways may have been the most expensive part of the project – deploying surveillance radars and aircraft or anti-air and anti-ship missiles may not incur nearly as much financial expenditure. In contrast, any military effort to neutralize Chinese defenses may incur significantly higher financial and human costs. Chinese cruise missiles out=range all but the most expensive standoff munitions, and recent simulations have indicated that concentrated, integrated Chinese SAM systems could hold off all but the most capable air forces. Though American air forces and standoff weapons could likely make short work of nascent Chinese island outposts in a conflict, the tyranny of distance the U.S. faces deploying from home or forward bases helps bring a potential Chinese military challenge from the South China Sea into greater focus.

China’s land reclamation represents a significant but limited potential increase in Chinese regional military capability, regardless of the specific militarization path adopted by Beijing. China has new airstrips where it had none before, along with defensive structures on islands that simply did not exist two years prior. Chinese denial of militarization rings hollow – these airstrips strengthen Chinese presence in peacetime and provide redundant military bases that could increase resiliency in wartime. A cursory examination of militarization options helps justify the concern of American officials over further Chinese military actions that have yet to occur. Any Chinese militarization would have limited military utility vis-a-vis the United States, but militarization would manifestly establish Chinese military superiority over its neighbors and heighten the potential for conflict that would draw in the United States – an outcome the United States would like to avoid.

Bonnie Glaser is a senior adviser for Asia and the director of the China Power Project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. John Chen is a research intern with the China Power Project at CSIS and a Master’s student at Georgetown University.