The Rebalance authors Mercy Kuo and Angie Tang regularly engage subject-matter experts, policy practitioners and strategic thinkers across the globe for their diverse insights into the U.S. rebalance to Asia. This conversation with Dr. Tom Kane – Senior Lecturer at the Centre for Security Studies, University of Hull, United Kingdom and author of numerous publications, including Strategy: Key Thinkers, Understanding Contemporary Strategy, and Chinese Grand Strategy and Maritime Power, among others – is the 26th in “The Rebalance Insight Series.”

What are the core elements of Chinese grand strategy and how have they evolved from the ancient period to the present day?

The founder of China’s Zhou Dynasty established the principle that his country should be a large state defined by its cultural ideals. Although China has split up at numerous points throughout its history, its leaders have consistently returned to this principle. They hold to it today. Moreover, as China has come into contact with powerful outsiders, Chinese leaders have become increasingly aware that, for their country to thrive as an independent state, they need to take full advantage of its geographical position and economic capabilities. These are the core elements of China’s grand strategy, and the government of the People’s Republic appears to be carrying out a successful long-term program of responding to them.

The most widely recognized parts of this program have been the economic reforms of the 1980s, and Beijing’s subsequent attempts to achieve national prosperity. As the PRC’s growing role in international trade has made it more influential, it has displayed an increasing willingness to engage with international organizations, and to lobby within them for its own interests. The PRC has also used its wealth to modernize its armed forces. Although its military capabilities remain modest when compared, for instance, to those of the United States, Beijing appears to be borrowing another concept from Chinese tradition and practicing the “empty fortress” tactic of using assertive behavior to achieve a reputation for power. Since neither China nor its potential opponents wish to escalate their disputes to actual war, this reputation often becomes reality – a concept examined in my Parameters analysis on China’s power projection capabilities.

How might Beijing use China’s leadership as the 2016 G-20 chair to advance China’s strategic interests?

The G-20 summit offers the PRC a chance to showcase its national successes and advocate its various policy initiatives. Thus, the summit allows the PRC to enhance its public image and perhaps increase its influence in high-level negotiations. The main strategic benefits which Beijing obtains by hosting this event summit are likely to be those of intangible “soft” power, but they may well be valuable nevertheless. Moreover, the PRC offers Chinese leaders an opportunity to reassure investors throughout the world that China’s economic future remains bright – and this could bring more material benefits.

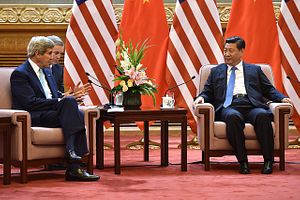

How has President Xi Jinping bolstered China’s leverage and influence through regional and international institutions?

One of the most dramatic changes in the PRC’s foreign policy in recent decades has been its new willingness to engage with international institutions. This change seems to parallel China’s increasing power, and thus the Chinese government’s confidence that it can influence those institutions’ decisions. The trend became obvious in 2001, when Beijing first joined the World Trade Organization and went on to adopt a new policy of much closer co-operation with the Association for Southeast Asian Nations. Dr. Wang Liqin incisively analyzes these issues in her book East Asian Economic Integration: A China-ASEAN Perspective (2014). Since these institutions manage matters of critical importance to China, such as trade, security and cross-border environmental issues many of the ways in which China works with them to bolster its leverage and influence are direct and obvious. The PRC uses its power within these institutions to pressure other members to defer to its position on a broader range of matters. Wang notes, for instance, that one of China’s motives in engaging with Southeast Asian regional institutions appears to have been to drive a proverbial wedge between those institutions and Taiwan. Xi Jinping appears to have continued the PRC’s successful policy of engaging with regional and international institutions, and of founding such new ones as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the New Development Bank.

Briefly assess the effectiveness of U.S. rebalance to Asia and its impact on Chinese grand strategy.

Strategy practically always involves making difficult decisions about allocating scarce resources. Given America’s current economic situation, and given the American people’s not-unreasonable reluctance to committing significant ground forces to resolving the ongoing conflicts in the Middle East the rebalance toward Asia is an effective way for Washington to obtain maximum international influence from its limited military assets. Disputes involving Asian countries increasingly concern issues unfolding in other parts of the world, notably Africa. Therefore, America’s leaders would be unwise to assume that physically placing military assets in Asia will automatically be the best way to gain leverage in Asian affairs.

The PRC’s initial response to America’s rebalance appears to have been to push forward with its grand strategy. If anything, it has behaved more assertively than ever. In recent years, for instance, the PRC established a controversial Air Defense Identification Zone over the East China Sea. Such measures appear to be attempts to demonstrate that China will not be intimidated. If the conflicts in the East Asian region were to escalate, the rebalance would complicate any Chinese attempts to use or threaten military force, but as long as tensions remain at their current level, little is likely to change.

What three scenarios – cooperation, competition, conflict – are plausible for the future of U.S.-China relations under a new U.S. administration?

It is virtually certain that there will be a mixture of all three! Xi Jinping has correctly noted that international climate negotiations are not a zero-sum game. The same is true of most other issues involving China and the other developed nations. Despite some of the rhetoric in U.S. political campaigns, China’s role in global trade, if nothing else, greatly enhances the likelihood that both Chinese and American leaders will continue to recognize this fact, and to maintain the mutually profitable relationship – with its occasional tensions – which they currently enjoy.