The term “49ers” refers to a group of bold individuals from all over the world who made the journey to California in 1849 in search of gold and great wealth. This gold fever and the associated gold rush is emblematic of the American push into the Wild West and the intrepid individuals who made a coast-to-coast United States possible. One of the main ethnic groups among the roughly 90,000 people who flocked to California in 1849 was Chinese, who crossed the vast expanse of the Pacific Ocean into unknown territory in search of gold. That same spirit would inevitably need to be present in those Chinese who would venture into the Siberian expanse in search of a better life. But even if the spirit is there, is there a modern-day analogue for the Californian gold that would trigger a rush?

The Sino-Russian border dynamic in the Far East have received relatively little attention in the past decade, even though it has the potential to be a hotbed for tensions between the two geopolitical giants as the century approaches maturity.

The overall dynamic between Beijing and Moscow has clearly been positive in the past year or so. From the march of the Beijing Honor Guard in the Red Square WWII celebrations, to the closing of major energy deals, China and Russia have been gravitating towards each other.

The forces drawing the two together are a mix of shared threats, common approaches to governance, and short-term objectives. The key word here is “short-term.” Even though these forces are relevant and observable, the relationship is also shaped by history and culture.

First, though, let’s consider the factors that draw Beijing and Moscow to speak a common language in the international arena: Washington and its presence in Central Asia, and also the U.S. and allied presence and actions in Eastern Europe and in the South and East China Seas, shared authoritarian ideas of governance with abundant state interference in the economy and tight control of the media and other information sources, and a common narrative on a “multipolar” world, with both countries trying to reinvent and reassert their role in the world, thus challenging the United States. China and Russia are also linked by membership in regional and international organizations such as the BRICS, SCO and UN Security Council.

Actions marked as aggressive by China and Russia in the South and East China Seas and in Eastern Ukraine, and in general in the entire Black Sea-Baltic Sea isthmus, are part of a containment strategy, reminiscent of the Cold War era and in response to perennial U.S. geostrategic objectives, such as maintaining control of the Rimland, as defined by Nicholas John Spykman. Aware of the potential for resource harvesting and industrial output that a political homogenous Eurasian landmass could offer, the United States and its Western European allies tweak their strategy to prevent cohesion in this vast area and control tangential points to its coast. This in turn drives China and Russia to overlook their own rivalry and adopt a common approach.

In the long-term, however, the China-Russia relationship encounters almost insurmountable odds. History is one of the main culprits here, with Beijing-Moscow ties strained by a series of unequal treaties, like the 1858 Treaty of Aigun and the 1860 Convention of Peking, both with major territorial consequences on China that reverberate until this day. Then there was Mao’s rejection of Soviet reforms after Stalin’s death and the subsequent antagonism within the Soviet bloc, along with numerous Cold War-era border skirmishes, both in the Western part of the border near Xinjiang and in the Eastern part of the border, near Manchuria. Another important culprit is geography. The border in the East, approximately 3,645 kilometers long, is porous by nature and has few natural barriers to restrict traffic. Yet another important factor geography brings to the equation is demography, which is at the core of the Siberian question in the Far East.

Many analysts have taken note of the demographic pressure of the Chinese population south of the border on the Russian population to the north. Some theorize that demographic pressure in conjunction with porous borders, numb governance from Russian central authorities, and a blind eye from Beijing could lead to a steady increase in the number of ethnic Chinese within Russian administrative borders, creating unrest and perhaps even ideas such as autonomy, with ironic help from the precedent set by Russia itself in Crimea.

The Demographic Question

Let’s tackle the demographic question first. According to information made available by the National Census Bureau in China, the 2010 national census gave the three provinces that form Manchuria, Heilongjiang, Jilin and Liaoning, a total population of 109,520,844 people. Inner Mongolia also has a periphery with the Russian Far East, but its provincial territory is stretched along the Mongolian border, making its approximately 25 million population less relevant here.

These three provinces are roughly the size of Turkey, and the distances between major Chinese cities, such as Harbin, and Russian border cities, such as Blagoveshchensk, Amur Oblast, is vast at 500 kilometers or more. So the Chinese bulge, defined as the Chinese territory south of the Russian Far East border that stretches in a straight line between Zabaykalsk, a Russian border town, to Vladivostok, via Harbin, is large and not easily accessible.

Russia’s most exposed subdivision to the Chinese border is the Amur oblast, with a population of 830,103 people, according to the official data of the 2010 national census. The second most exposed region is Primorsky Krai, with approximately 1,956,497 people, mostly concentrated around Vladivostok. Another Russian federal subject area that has a border with China is the Jewish Autonomous Oblast, with a population of 176,558 people. The last of the federal administrative areas is Khabarovsk Krai, with a population of 1,343,869 people. So roughly, the regions that neighbor China are home to 4.3 million Russians.

So 4.3 million Russians facing around 109 million Chinese? In fact, this proportion overstates the imbalance, as a significant portion of the Chinese population is quite far from the border and gravitating towards major urban centers to the south. The real Chinese demographic pressure on the Russian border is generated by those who live close to the border. The Chinese bulge, roughly 570,000-600,000 square kilometers in area (a delimited map can be found here) has as its main urban center Harbin, with a population of 5,282,093.

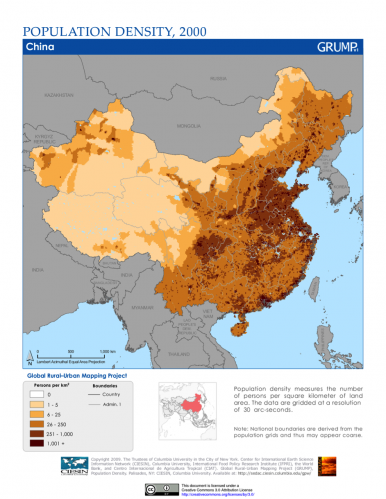

To assess the total population living within the bulge, I used a population density map (figure 1) provided by Columbia University’s SEDAC (Socioeconomic Data and Applications Center), a Data Center in NASA’s Earth Observing System Data and Information System, and the online area tool. With these tools, we can assess the population with SEDAC’s own population estimation service tool (PES). The data for the population density map is from the year 2000 and the data used in PES is from 2005.

Figure 1 – China Population Density. Source: SEDAC

A rough approximation shows that 70 percent of the area has a population density within 26-250 people per square kilometer, a generous interval. Another 20 percent is in the 6-25 people per square kilometers interval, and about 10 percent of the bulge is in the 1-5 people per square kilometers range. For simplicity, I used median values for these intervals, so we end up with a total of 57,236,000 people. To this result I would add the urban population of Harbin, which is clearly represented in the density map as a region falling within the 1001+ range. This takes us to a total of 62,518,093 Chinese people living within the bulge. The trouble with this estimate is the fact that the 70 percent interval is quite large and real values versus median values might influence the final result dramatically.

The PES tool tells us that for approximately the same area, including Harbin, the population is 35,484,550 Chinese people living within the bulge.

This estimate, although rough, gives a more precise number of those Chinese most likely to consider emigrating to the Russian Far East, than the total of 109 million people living within the Chinese provinces adjacent to the Russian border.

Another aspect of demography is qualitative. What are some of the basic traits of these 35.4 million people? If the population is young and the birth rate is positive, the tendency to emigrate increases. If the population is aging fast there will be clearly lower demand for adventures in areas with a tough climate.

The latest available data from the National Bureau of Statistics of China (NBS) is from 2014. Unfortunately, the age groups are divided only into three main intervals, 0-14 years, 15-64 years, 65+. The 15-64 years interval, or the working age interval, accounts for approximately 71 percent of the total population of Liaoning, 71 percent in Jilin and 73.5 percent in Heilongjiang.

These are well over the national figure of 63.8 percent, and could potentially signify that a larger segment of the population are potential migrants. Lacking more granular information, however, we cannot know how many people are between 18-35 years, an age cohort much more likely to emigrate than the group aged 36-65 years. Still, applying the 73 percent to the 35,484,550 figure calculated above gives us approximately 25,903,721 million people who could migrate towards the Russian Far East, as the working age population in the periphery of Russian borders.

The birth rates, according to the NBS, for 2014 in Heilongjiang, Jilin and Liaoning are 7.37 percent, 6.62 percent and 6.49 percent, respectively, and all have natural growth rates larger than 0. Natural growth rates in Amur Oblast, Primorsky Krai, Jewish Autonomous Oblast and Khabarovsk Krai are negative, according to official data from the Federal Service State Statistics.

Numbers are very important in determining demographic pressure, but any migration from China to the Russian Far East must have a driving force behind it. This would typically be economic opportunity and/or better living conditions. According to the NBS, here are some standard of living indicators for the Northeastern provinces, from 2012: The average number of persons per household is 2.68, with an average of 50 percent employed and 22,816.19 yuan ($3468) per capita income with a 20,759.9 yuan disposable income. Per capita annual living expenses were 14,968.5 yuan, of which 34.58 percent is for food, 12.83 percent is for transport and communications, and 13.14 percent is for clothing.

The Northeastern provinces display very similar per capita incomes, disposable incomes, and living expenditures with the Western provinces, with values slightly higher than the Central provinces but with a discrepancy compared to the Eastern Provinces where the biggest Chinese coastal urban centers are. The adjacent Eastern Provinces would surely be a much more alluring option for Chinese in Manchuria who would like a better life.

A significant factor in this is transport infrastructure. A well-known and somewhat clichéd Chinese proverb says that “If you want to be rich, you must first build roads.” For young Chinese living in Manchuria who want to migrate, the Southern route is far more accessible than the Northern route. Basically, there are no highways connecting Russian border towns to Chinese cities aside from G1211 highway near Blagoveshchensk.

Facts on the Ground

The Russian Far East might be considered much less exciting than other more volatile geostrategic areas, such as the Middle East or Central Asia. But Moscow has begun to look to the Far East, as The Diplomat has already presented in a three-part series. This pivot aims to gain from the geopolitical options the Pacific theater brings to the table and enrich Moscow’s base of negotiation and trade. The newly established East Economic Forum is a platform in which economy and bilateral (and even multilateral) ties, might grow within the region, reaching as far as India. The federal government’s efforts to build a new economic and social foundation in its Far East districts can be characterized as holistic in their approach. Legislation on priority development areas (PDAs) in Russia, signed by president Putin in 2014, explicitly refers to the Far East as the beneficiary of various incentives such as tax reductions and subsidies, in the first three years after the law came into effect. Another law that should have incentivized local and foreign entrepreneurs is that providing tax holidays for the first two years for businesses that set up shop in the Far Eastern Federal District, although it has had some trouble being implemented.

Vladimir Putin, at a meeting in April 2015 with high ranking officials on Far East governance, such as Deputy Prime Minister and Presidential Plenipotentiary Envoy to the Far Eastern Federal District, Yury Trutnev, and Minister for the Development of the Russian Far East, Alexander Galushka, said regarding the tax holiday law: “I hope that you will work through the issues with the regional authorities in the Far Eastern Federal District so that all problems that can be settled using these instruments will be resolved effectively and these instruments will be put to good use.”

At the same meeting he made an interesting reference to the regional plan of offering a hectare of land for good use: “As you know, we gave this idea our support and took the necessary decisions. The important thing now is for the land allocated to be in attractive areas, and for it not to just then be put on the market. Of course, we also must make sure above all that, once allocated, this land is not transferred immediately to foreign legal entities and individuals.” This is of particular relevance for the Siberian question because there has been speculation that it would boost the Chinese population in the area further. The issue is not that simple. The giveaway plan and its adjacent laws specifically prohibit foreign ownership, renting and donating the plot to foreign individuals or companies, at least for the trial period of five years. Still, it could trigger some increase in Chinese interest as the area should develop more and more jobs would be available. Furthermore, there are concerns among the local media that this scheme will only benefit oligarchs who will use subterfuge in order to seize land and eventually tap a cheap Chinese workforce, probably from the rural population of the Chinese bulge defined above.

This program targets the larger Siberian basin, from Central Russia to Sakhalin Oblast, which is not the focus of this analysis, as Chinese demographic pressure is more likely and acute near the border.

The 2010 Russian census results, at a first glance, don’t paint a striking picture of rising rates of ethnic Chinese. But it does tell us that ethnic Russians are declining, and in 2010 numbered around 111 million people. Chinese are not mentioned within the notable foreign ethnic groups that live in Russia, as a whole, with former Central Asian Soviet countries, such as Uzbekistan and Tajikistan taking the lead.

Alarmism

According to this study undertaken by Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in 2009, “the number of Chinese visiting, working, or living in Russia has been among the most wildly abused data points in a country known for statistical anomalies.” Public authority figures and analysts have distorted the extent of Chinese demographics in Russia, adding to the sense that there is an invisible invasion going on. The text highlights a statement from Putin himself during a visit to the border city of Blagoveshchensk in 2008, when he said to the residents that if they do nothing to turn the economic tide of the region, their children will speak Chinese. This kind of rhetoric was not at all new. The same paper underlines alarmist statements from Russian officials such as Evgenii Nadzarenko, governor of Primorskii Krai from 1993 to 2001 and Victor Ishaev, former governor of Khabarovsk Krai and former presidential plenipotentiary envoy in the Far Eastern Federal District of Russia. The latter said in July 1999 that “all the land in Russia’s Far East will be bought up by Chinese. […] The peaceful capture of the Far East is underway.”

Alexander Shaikin, former head of the Russian-Chinese border control, said on July 29, 2000, that during the last 18 months approximately 1.5 million Chinese crossed the border illegally. As Stratfor acknowledged at the time, it is impossible to clarify this figure exactly, which was subsequently countered by Yury Akhipov, head of the Russian immigration directorate, saying that there is significant shuttle traffic. According to the latest available data on international migration from the Federal Migration Service, the official number of Chinese immigrants in Russia for 2014 is 10,563, which is far below the alarmist scenarios and figures from various analysts and public figures and indeed, conspicuously small given such a large border.

Khabarovsk and other border cities are becoming much more relevant, both in Russia’s Far East policy and for assessing Chinese involvement in local socioeconomic affairs.

The city of Khabarovsk serves as the administrative centers of Khabarovsk Krai and it is the second largest city in the Russian Far East after Vladivostok. In a 2009 Guardian article, Tsi Ke, a 25-year-old restaurant owner, said, after living in Khabarovsk for over a decade at the time the article was written, that “I’ve had a few relationships with Russian girls. But I’ll end up marrying a Chinese one. In China we believe a wife should stay at home a lot and be like a daughter to your own parents. For us, marriage isn’t just between two people but between two families,” hinting at a cultural difference that could disrupt any homogenizing process between ethnic Chinese and ethnic Russians.

Russian Authoritarianism

Olesya Gerasimeko, a Moscow based journalist, described Russian authoritarianism in Primorye Krai, after protests over an increased tax on second-hand imported cars, mainly Japanese imports in 2008. “We always protested peacefully: cheerful people in the squares with homemade flags, avenues closed off the night before – no big deal. But suddenly we were being beaten by Moscow police in the centre of our own city. Shock therapy, they called it,” she quoted a local journalist as saying. In another incident that occurred in 2012, a group of young boys declared war on the local police in Kirovsky, a village in the Primorye region near the Chinese border. The story is of corruption and brutality within the local police force and hints of a Russian population that is disenfranchised and wary of central authority.

Blagoveshchensk has its own tale. In 2015, the Confucius Institute based in Blagoveshchensk’s State Pedagogical University, was under scrutiny by the local prosecutor’s office. The formal charge was that it was run as a non-profit organization but it was hiring Chinese nationals and avoiding taxes. The unspoken suspicion was that the institute was undermining Russian authority in the region and promoting ideology that was harmful to Russian interests. The head of the International Education and Cooperation Department at the Pedagogical Univesity, Nikolai Kukharenko, told Kommersant that the institute is a non-independent entity that is part of a joint academic project between the Belarusian State Pedagogical University and the University of Heyheskim, an ambiguous response. This is not the first incident involving this type of cultural organization in Russia. According to the same article, in 2010, the Confucius Institute in Yakutsk, also in the Far East, had been closed on FSB accusations that it was “promoting the penetration of the Chinese ideology and economic expansion to the territory of Russia.”

In a statement made by Nikolai Kukharenko to an independent journalist, there’s something of a Potemkin village story going on in Blagoveshchensk. The nearby Chinese Heihe city has a glittering facade, attracting Russians and signaling another economic story on the other side of the border, although some Russians deem the Chinese “twin city” a chaotic place.

Could in fact it be Russians who are attracted to cross the border, at least as shuttle travelers, accessing more interesting markets and produce? With its Far East realignment policy, Moscow is trying not only to energize the East in line with domestic objectives, but also to compete with China’s regional soft power, understanding that influence will be won through culture, time, exposure and economics. Investments flows in the area have been earmarked. Khabarovsk Novy International Airport is undergoing maintenance and upgrades with new rescue stations, meteorological equipment, and double the passenger capacity, with completion slated for 2017. Vostochny Cosmodrome is another mega-project located in the Far East, with an investment topping $3 billion. The cosmodrome should eventually replace Baikonur as Russia’s main space center, but has suffered delays as management personnel have been charged with embezzling state funds. Energy geopolitics in the region and in Asia has already been thoroughly analyzed in This Diplomat piece.

It is becoming increasingly obvious that Russia is focusing its ambitions for influence in the Far East on the Blagoveshchensk-Khabarovsk-Vladivostok triangle. The first task Russian authorities will have to undertake in mitigating a Chinese threat – inflated or real – is to reassure its own citizens that there is a central authority that cares for their wellbeing and not only for their assured loyalty and submission.

Overstated, But Real

We’ve learned that the demographic pressure China exerts on Russia across its border falls short of the hype, but at the same time is real. We saw that the demographic ratio is approximately 4.3 million Russians to 25.9 million Chinese within the 15-64 years age bracket, or almost six Chinese of an age most likely to emigrate for every Russian living in Russian territorial units adjacent to the Chinese border.

Birth rates are positive for the Chinese and negative for the Russians. This is not encouraging for the Russians, but we have to take into account that for Chinese on the border more economic opportunities and a more robust transport infrastructure lies to their south, not to their north. In other words, young Chinese in search of a better life will most probably choose to take their chance in an Chinese urban environment rather than a harsh rural Russian environment.

Moscow’s thrust to revitalize the region will also attract more Chinese, not only Russian citizens from other areas. The biggest danger is not the increase in ethnic Chinese within Russian borders, but corruption that sees money flow to oligarchs rather than entrepreneurs, which will do little to distribute wealth and reinvest in the region. We have also seen that local interactions between Chinese and Russians are in general commercial in nature and peaceful, and the presence of corporations and central rule may only increase the defensiveness of the two populations towards each other.

Returning to the initial story, of the Chinese 49ers, there is no acute gold fever that might drive their modern counterparts to cross the border into Russia. The reality is much more balanced and indeed Chinese prices and commodities sometimes drive Russians to cross the border themselves. In the meantime, Moscow is looking for its own generation of Russian 49ers, to build up its own critical mass of people in its Far East and take land or forest for exploitation.

It is likely that the Chinese population will increase within the Russian borders, albeit at a very slow rate. Also, it is likely that Russia, even though it has taken serious action to develop the Far East, will not be able to compete with China or Japan in terms of economic output in the Northwestern Pacific region. Nevertheless, Russia will remain a powerful voice in the region due to its position on the Security Council and the fact that it is a nuclear state. It will recuperate in the following decade due to the policies described above, but in the long run, demography, complexities on its Western and Southern peripheries, falling oil prices, and perhaps a global shift away from fossil fuels will eventually increase the pressure on Moscow and force it to make some difficult choices. If the Far East is to turn into a powder keg between the Russians and Chinese over the grievances of a large population from the latter, it will probably happen after 2050. In the decades until then, it is unlikely to explode as an issue on the world stage.

Dragoș Tîrnoveanu is co-founder and chief editor for the Romanian think tank Global News Intelligence.