In a recent article for The Diplomat, Nhung Bui essentially argues that Vietnam should abandon its non-alignment foreign policy because such course of action provides Hanoi with more flexibility in the longer term and best serves Vietnam’s security interests in the face of an increasingly assertive China. Although her arguments are reasonable and merit a close reading, I ultimately disagree with her analysis and conclusion. Abandoning non-alignment without provoking Beijing is hardly realistic and in any event, pursuing the current hedging strategy is still the best way to serve Vietnamese national interests.

Nhung opens by arguing that “there is a middle path that Vietnam can walk by simultaneously abandoning the non-alignment policy as well as avoid provoking China” and that given General Secretary Trong’s conservative and possibly pro-China credentials, he is well-suited to convince Beijing of Hanoi’s benign intentions in the event Vietnam abandons its non-alignment principle and more specifically, the “three Nos” policy. Theoretically, she is correct but realistically, this is impossible for several reasons.

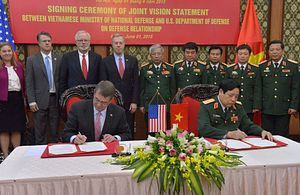

First of all, Chinese leaders are not naive, they certainly know that in the past few years, Vietnam-U.S relations have been much better than Vietnam-China relations. After all, Obama broke the protocol in giving Trong a head-of-state’s welcome and the U.S has eased its arms embargo on Vietnam. While I cannot recall the last time the U.S and Vietnam had a diplomatic crisis, the May 2014 oil rig crisis between China and Vietnam easily comes to mind. Beijing is also not under any illusion that Vietnam is buying Russian submarines in order to counterbalance the U.S Navy. In this context, I could not imagine how abandoning non-alignment could be interpreted charitably in Beijing. Thus Nhung’s claim that by abandoning non-alignment, Hanoi would allow Beijing to “see an opportunity” to form an alliance with Hanoi in the future, is largely wishful thinking. As long as the South China Sea (SCS) dispute remains, the chance of a Sino-Vietnamese alliance is practically zero.

Secondly, while she is right that Trong is better positioned than Dung to convince China that “even if Vietnam drops its non-alignment position, it would not form an alliance with an outside actor any time soon,” this is still problematic for two reasons. First, just because Trong can do a better job than Dung does not mean he would be able to successfully convince the Chinese. After all, anti-Chinese sentiments in Vietnam is only growing stronger by the day and in Vietnam, even the top leader cannot impose his will on the rest, given institutional structure. Second, even if Trong were able to do so, knowing that Vietnam would “not form an alliance with an outside actor any time soon” is hardly assuring from Beijing’s perspective. After all, the implication is that one day Vietnam might seek an alliance and that would not be something China looks forward to.

Even if abandoning non-alignment without provoking Beijing were realistic, it is still not the best course of action for Vietnam. Nhung apparently assumes that the United States or Japan might seek an alliance with Vietnam in the future. Yet this is highly unlikely. The United States is already overstretched in terms of resources and commitment and it would not formally pledge to defend an ally that it has little control over for fear of entrapment, which is the same reason why the U.S rejected a defense treaty proposal in 2015. Given Japan’s history with China, Tokyo would not to exacerbate tensions further by formally committing to an ally whom Tokyo would probably not able to defend given the distance and its military capacity. Thus abandoning alignment does not invite others to form alliances with Vietnam. If Vietnam’s security were so vital to U.S interests, they would come to Vietnam’s aid anyway, just as they defended Kuwait in the face of Iraqi invasion despite having no formal alliance with Kuwait.

Contrarily, genuine non-alignment actually gives Vietnam some real diplomatic flexibility. While I am pessimistic about resolving the SCS dispute diplomatically, I also believe that abandoning non-alignment and therefore provoking hostility from Beijing would mean that there would be absolutely no chance of resolving this dispute peacefully through diplomatic means. This diplomatic flexibility also allows Vietnam to continue benefiting from its ties with China for the time being while reducing the risk of abandonment for Vietnam in the unlikely event that the U.S and China could somehow cut a deal in the future.

The only way for Vietnam to inch closer to the U.S and avoid provoking China at the same time is to actually pursue the current hedging strategy. After all, the current strategy does not force Vietnam to be exactly halfway between the two superpowers. It only requires Vietnam to avoid “leaning to one side.” For the time being, this seems tolerable to Beijing, which is important because it gives Hanoi some breathing room to maneuver.

Lastly, the current policy gives Vietnam the most leverage in dealing with both superpowers. On the one hand, if China knows that Vietnam is definitely siding with the United States, Hanoi would lose all bargaining power with Beijing and if it knows for sure that Vietnam will not join the U.S camp, Beijing will not shy away from more intense pressure on Hanoi. On the other hand, if the United States knows for sure that Vietnam will not turn pro-U.S, it will most likely not assist Vietnam but if it knows for sure that Vietnam is dependent on U.S security guarantee, Hanoi would have no leverage in dealing with Washington. Either of these scenarios is bound to happen under Nhung’s policy prescription and neither of them serves Vietnam’s security interests. The current strategy can avoid both because it adds a layer of uncertainty to Vietnamese strategic intentions.

Given the current deadlock in the SCS, everyone wants a change and abandoning non-alignment does just that. However, we have to be mindful that change is not always good and in abandoning non-alignment, Vietnam might needlessly provoke China and endanger its security, without receiving anything tangible in return.

Ngo Di Lan is a PhD student at Brandeis University, where he focuses on U.S foreign policy and U.S-China relations. He is also a research associate at the Center for International Studies (SCIS) at the University of Social Sciences and Humanities in Ho Chi Minh City.