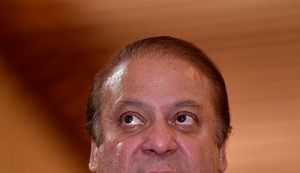

Halfway through his tenure as Pakistan’s third-time prime minister, Nawaz Sharif’s political challenges seem endless as he stumbles from one crisis to the other. Barely a year after Sharif survived a political sit-in against his government, over alleged electoral fraud in the 2013 general elections by his political arch-foe Imran Khan; once again, he is in the eye of the storm.

The prime minister has long struggled with increasing public discontent, growing civil-military imbalance, security challenges, and internal political strife with the opposition. The Panama Papers revealing Sharif family’s offshore properties in London, and the external challenges emanating from declining relations with the U.S., India, and Afghanistan have further increased his political predicaments.

At the root of his current political troubles lie Sharif’s penchant for power accumulation, his centralized style of rule, and his personalized governance model involving his kitchen cabinet of close friends and family members. His months-long absence from sessions of parliament has furthered earned him the ire of the opposition. As a result, most policymaking on key internal and external issues has taken place outside parliament, raising concerns about merit-based decision-making and transparency, the essence of democratic governance.

The lack of transparency and parliamentary oversight into policymaking has strengthened the impression among opposition parties that development projects are awarded to family friends and business associates. The opposition believes that Sharif has used his political power to expand his family wealth and businesses.

Sharif’s most formidable political challenge since he took office in 2013 is the fall-out of the Panama Papers, which has taken his moral authority to its nadir. The prime minister is likely to survive the current crisis but it will further weaken him. Certainly, the situation is graver than Imran Khan’s 2014 political sit-in. In contrast to that crisis, when major opposition parties firmly supported the prime minister, this time, they are united with Imran Khan’s Pakistan Tehrik-e-Insaf (PTI, Pakistan Justice Party), demanding Sharif’s resignation if a high-powered judicial investigation establishes financial misappropriation and money-laundering by the Sharif family.

Currently, there is widespread disagreement between the government and the opposition over the scope of inquiry commission’s terms of reference (TORs). The opposition wants pointed TORs under a new law that mandates the commission to probe specifically the propriety of the Sharif family’s offshore assets. In addition, the opposition insists that the new law should empower the commission to utilize all means, including assistance from international financial audit firms and relevant government agencies, to get to the bottom of the case. On the contrary, the government wants the investigation of all the Pakistanis named in the Panama Papers, including the prime minister, along with those who had loans written-off in the past. Presently, a 12-member parliamentary committee of government and opposition has been formed to overcome the differences over TORs.

Meanwhile, the Supreme Court chief justice Anwar Zaheer Jamali has declined the government’s request to constitute a judicial commission to probe the Panama Papers allegations, given the open-ended nature of the TORs and the weak law under which the government has requested him to form the commission. Jamali has maintained that a commission cannot be formed until the issue of TORs is not resolved. Moreover, he has asked the government to pass new legislation to form the commission and provide names and lists of individuals whose cases the intended commission should probe.

Civil-Military Imbalance

At the same time, the growing civil-military imbalance has further added to prime minister’s political predicaments. Serious differences persist between the government and military over the impending counter-terrorism operation in Punjab, where Sharif has his power base. After the Taliban’s Easter bombing in Lahore in March, the military unilaterally decided to launch the operation in Punjab. The Punjab government, led by Nawaz Sharif’s younger brother Shahbaz Sharif, disagreed with the army’s involvement and the lead role in the operation. The government maintained it was their prerogative to decide which force would be used in the operation.

Pakistan’s top military brass is also not happy with the prime minister’s deafening silence over the arrest of Indian spy Kulbhushan Yadav from Balochistan. The government did not take up the issue of Yadav’s arrest at different international forums as fervently as the military wanted. Moreover, in the backdrop to the Panama Papers, army chief’s public statement about across-the-board accountability coupled with a purported news leak regarding the dismissal of eleven military officers from service on corruption charges was interpreted as a pressure tactic pushing the government to come clean on corruption charges and start holding corrupt politicians and civilian officers to account.

On the external front, relations with Afghanistan have deteriorated alarmingly in recent weeks following the Taliban’s refusal to participate in the peace process initiated by the Quadrilateral Coordination Group – comprising the U.S., China, Pakistan and Afghanistan – and the launch of their annual spring offensive. The death of Mullah Mansour in a U.S. drone strike further complicates matters for Pakistan.

Meanwhile, Kabul has exerted pressure on Pakistan to take action against the Haqqani Network. The tone in Washington has also changed following Pakistan’s inaction against the Haqqnis, despite its commitments to the contrary. Congress has blocked the Obama administration’s move to sell eight F-16 fighter planes to Pakistan on subsidized rates under the Financial Military Financing (FMF) progam. It has also conditioned the continuation of future military aid to Pakistan with specific actions like a crackdown against the Haqqani Network.

Similarly, the thaw witnessed in India-Pakistan bilateral relations following Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s surprise visit to Pakistan has dissipated. The deadlock over the Pathankot Airbase attack investigations has taken the peace process back to square one. At present, the two South Asian rivals are locked in a heated diplomatic tussle at different international forums on a range of issues. Pakistan, with Chinese help, is opposing tooth and nail India;s quest for permanent membership of the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) and its entry into the Nuclear Supplier Group (NSG). China, at Pakistan’s request, also blocked the Indian move in the UN to get Masood Azhar, head of Jasih-e-Muhamamd militant group, declared an international terrorist. In contrast, the Indian lobby in Washington has succeeded in convincing U.S. lawmakers to block the sale of F-16s to Pakistan, along with getting Pakistan’s tactical nuclear weapons program declared a major international security concern in the 2016 Nuclear Security Summit.

Given Pakistan’s volatile political environment, if the government-opposition disagreement over the TORs is not resolved, things could take an unexpected negative turn. Imran Khan has already threatened street agitation and a sit-in in front of prime minister’s Raiwind residence. The longer the crisis persists, the higher the chances of a political meltdown, something that Pakistan cannot afford at this juncture.

Abdul Basit is an Associate Research Fellow at the International Center for Political Violence and Terrorism Research (ICPVTR) of the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Singapore. He can be reached at [email protected]