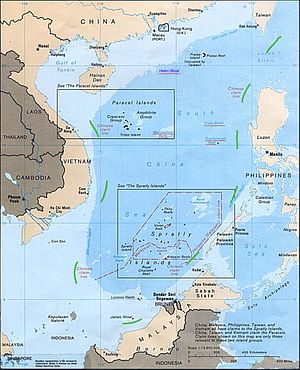

China has not precisely articulated – in terms familiar to sea lawyers or diplomats – what its nine-dash line in the South China Sea means. That ambiguity leaves plenty of room for possible over-interpretation, particularly when coupled with some of the actions that China has taken in response to perceived incursions within the area bounded by that line.

At one end of the spectrum, the line could be read as a maximalist claim to sovereignty and control over all of the features, land, water, and seabed within the area bounded by the nine-dash line. This is indeed what many states fear. In terms of the law of the sea, this doesn’t make much sense because it appears as a conflation of the concepts of sovereignty and jurisdiction – and no coordinates for islands or baselines have been provided, as is required under law.

Described loosely, sovereignty is like ownership of property domestically whereas jurisdiction roughly equates to an ability to benefit from or license the use of specific produce in an area (like the fish and hydrocarbons within your exclusive economic zone [EEZ] or a mining lease for certain minerals). However, it doesn’t mean that you can impose conditions on navigation or control over all activities within that area as if you owned it. China does not seem to have expressly said that this is what they mean by the nine-dash line, but some of its behavior and rhetoric suggests so. In particular, China has reacted strongly to freedom of navigation and overflight operations within the South China Sea – including in areas that are at most an exclusive economic zone of some state. See the heightened level of Chinese aircraft intercepts of U.S. overflights of the South China Sea during the last year, whether near features that China claims or not, and accusations of sovereignty violations.

This conflation of concepts or strategic ambiguity is probably a useful tool for buying time if you haven’t quite figured out what you want to do and how you want to lay claim to certain features (and enforce that claim). However, it can also be destabilizing. Compounding this complexity is the idea of “historical rights.” China has used this phrase not just in connection with claims to sovereignty over land (where history is relevant), but to maritime rights and jurisdiction beyond the territorial sea – where it is not. The only exception is traditional fishing rights, recognized by the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. But what China is on about is something quite different. It seems to be arguing a counter-narrative that the law is somehow different in the South China Sea.

In the face of the current arbitral tribunal deliberations in The Hague and international criticism, Chinese scholars and others assert that they abide by UNCLOS, but that is not the whole story – a different set of legal principles apply in the area. Put another way, China is saying: of course we comply with UNCLOS – but that isn’t the right law to apply here.

Trial lawyers the world over will recognize this as a well-known legal tactic, and it can be addressed as such. We can look at the merit and substance of it. But by tip-toeing around it we are privileging historical rights as some sort of special-case argument that applies only to the South China Sea and are at risk of mythologizing it.

At the other end of the spectrum of what China might mean with the nine-dash line is that the line represents a “box,” inside of which China claims sovereignty over any high-tide elevation and jurisdictional rights over any corresponding maritime zones (e.g., territorial sea and EEZ or continental shelf) generated by that feature.

Such a clarification would be in line with what China said about its sovereignty claims in its reservation when it ratified UNCLOS in 1996 and some aspects of their diplomatic protest notes (2009 and 2011) in response to the 2009 Malaysia/Vietnam extended continental shelf claim in the South China Sea. Such a clarification would not make other claimants happy as China would still be claiming sovereignty over territory that Vietnam, Malaysia, the Philippines, and others variously claim. Under this interpretation, the nine-dash line would be incomplete and insufficient as a claim, but not necessarily inconsistent with UNCLOS, provided that China also recognizes freedom of navigation and overflight in areas beyond 12 nautical miles from any naturally formed (as opposed to artificial) high tide elevation.

This is all highly technical, but it is the difference between claiming that the South China Sea is an internal Chinese lake or saying that China has some outlying islands off its coast which generate maritime zones. In the latter case the waters between the Chinese mainland and the islands are international for the purposes of military and civilian naval traffic.

In December 2011, Assistant Foreign Minister Liu Zhemin, the senior Foreign Ministry spokesperson from the Department of Boundary and Oceans Affairs Directorate, stated that China respects freedom of safety and navigation in the South China Sea and that the Chinese government has always maintained the right to freedom of navigation and overflight in the South China Sea as a right enjoyed by all countries in accordance with international law.

That statement would support the second interpretation. Statements in recent Chinese official publications and in the Chinese non-submission to the arbitral tribunal in The Hague make a similar point. Interestingly, the Chinese comments about navigational freedom highlight the importance of this for trade or commercial navigation.

International law makes no distinction between the navigational freedoms enjoyed by military and civilian vessels in the EEZ and the high seas. But it looks as if China may be preparing to do so.

In a recent essay in the National Interest, Fu Ying and Wu Shicun made the same points about safety of navigation and commercial shipping routes and went on to describe the South China Sea as an “important passage for the Chinese navy to sail the wider sea” — a curious and perhaps telling phrase. The authors also stated that clarifying what the nine-dash line means would escalate tensions. It’s difficult to see how that would be the case.

The second interpretation of the nine-dash line would also be supported by the approach that Taiwan has taken in recent years. The map of the nine-dash line is based on a map originally issued by a department of the Republic of China that showed 11 lines forming a U-shape in the South China Sea. In 1948, the ROC government declared its sovereignty and the right to maritime resources over the islands and reefs within the lines. When the PRC was established it recognized that line. Since 2005 Taiwan has slightly adjusted its claim to focus on the islands, their surrounding waters, and continental shelf rather than the whole body of water in the U-shaped line. In particular the ROC “suspended its claim to the entire waters” within the line in December 2005. It continues to claim sovereignty over land features within the line.

It is possible that The Hague arbitral tribunal could “read down” the nine-dash line in the above manner so as to make it not inconsistent with UNCLOS.

The eve of the anticipated arbitral ruling and high level regional summits present an opportunity for China to clarify what it means by the nine-dash line. Were China to expressly clarify that the second interpretation of the nine-dash line is what it intends it would lose nothing in terms of its long-maintained claims to territorial sovereignty (and corresponding maritime jurisdictions) in the South China Sea. But it would create a higher degree of certainty for non-claimant states operating in the area. It would also provide more certainty for the claimants.

Marina Tsirbas is Senior Executive Adviser, Policy Engagement at the National Security College, Australian National University.