A few months ago in London, an off-the-cuff conversation with a former BBC journalist on the global coverage of the Kashmir dispute yielded a succinct response.

With fires raging across Syria, Iraq, and central Africa, Kashmir falling from international radar, he argued, is normal.

“The radar will not catch it until many people are dying,” he explained.

What he meant was that Kashmir is no longer a spicy story for global editors. With suicide bombers tearing through Iraq, killing hundreds in a single blast, rebel fighters of the so-called Islamic State downing Russian helicopters, the Taliban taking their fight deep into Kabul, a rise in hate crimes in Europe, and the tussle for power in the South China Sea, Kashmir is indeed a small story in comparison — a one-inch column fit for the inside pages.

But now Kashmir is back on the international radar — precisely because, as the journalist predicted, many people are dying.

As I write this piece, 34 mourners protesting the killing of talismanic rebel commander Burhan Wani have already been shot dead by Indian soldiers in Kashmir’s streets. Over 1,400 have been injured; some of them may lose their eyesight as government forces have been using high velocity pellet guns — which eject 600 high-velocity iron balls at one go — to break up the protests. Over 100 Indian police have also been injured, according to officials.

The shaky peace after deadly 2014 floods has shattered completely.

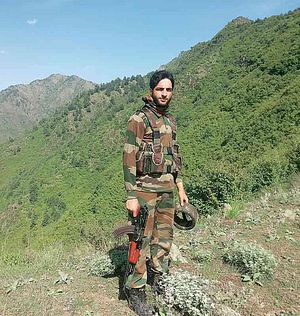

It started with a thought-out plan to kill Burhan Wani, popular among the locals but the most-wanted rebel commander of the pro-Pakistan Hizbul Mujahideen group, four days ago in south Kashmir. The government wanted pro-Indian politician Mahbooba Mufti to win the local polls before the operation, according to a top Indian newspaper.

The killing was enough to set Kashmir on fire.

Soon angry protesters marched into the streets of Kashmir. Over 300,000 estimated mourners reached Tral to offer the final prayer before the rebel’s burial. Shams Irfan, a local journalist who traveled to Tral, told Al Jazeera that the mourning and demonstrations were “the biggest he had ever seen.” Others observed over 40 back-to-back funeral prayers offered, which is now a record in Kashmir’s history (and perhaps elsewhere in the world). Previously it was another rebel Dawood Sheikh (or Chotta Burhan) who was given a hero’s funeral in Kashmir, when the mourners offered the last prayers eight times in a row.

Like the funerals of the rebels in the 1990s, even those of foreign fighters (or Mehman Mujahid, “guest rebels,” as Kashmiris call them), are highly charged. Last year in October, three Kashmir districts dueled to lay claim of the body of a Lashkar-e-Taiba rebel leader. Each wanted to have a privilege to bury their “martyr.”

At Burhan’s funeral, the crowd, eager to have a last glimpse of the fallen India’s “terrorist” and Kashmir’s “hero,” swelled so much that the burial had to be delayed continuously.

Last year in August, when I traveled to Tral — an area of pristine waters and tall deodar forests with deep-rooted anti-India sentiments — the mood was as if people were waiting for this moment. The anger was palpable, even among the minority Sikh community that has been living in Muslim-majority Kashmir for centuries.

“We call him our Burhaan Bai (brother),” a group of Sikh vacationers told me in the Shikargah forests.

Burhan Wani, 21, was only 15 when he opted for the gun. He led a band of quality, educated, and media-savvy active rebels in disputed Kashmir until his last gunfight.

“An all-rounder cricketer and a smart student, my son always scored higher than his contemporaries,” his father Muzaffar Ahmad Wani, 53, principal in a government school told me then.

Wani confirmed that the final push came when Indian soldiers beat his sons, including elder son Khalid Wani, in 2010 without provocation.

“He couldn’t bear the humiliation and decided to join the rebels to fight for independence from India,” he told me. He then described how his two-floor home in Tral had been raided and ransacked by soldiers over a hundred times since 2010.

Last year in April, Khalid Wani too was killed in what many say was a staged gun battle.

But Burhan didn’t stop there. In his videos he would hail minority Sikhs but warn members of local police against fighting “India’s war” in Kashmir.

“Burhaan is used to social media. Sometime back he used to threaten top army and police officers on [the] phone. But we never managed to trace him,” a top counter-insurgency police official told me.

Since 2014, Burhan’s group managed to snatch 50 weapons from Indian soldiers, including Russian AK-47 assault rifles, SLRs (self-loading rifles), INSAS (Indian Small Arms System) rifles, and carbine sub-machine guns.

“If this trend enters Srinagar [the summer capital], it’s going to be a big question mark on the overall gains we’ve made against militants for years together,” the official warned.

Now protesters are back in the streets, including in Srinagar. Images coming from Kashmir show pitched battles between stone-throwing locals and Indian soldiers. The hospitals are facing an emergency situation. The blood supply is running short; so are the medicines needed to treat an army of injured being ferried in ambulances often targeted by soldiers on the way.

The Indian media has thrown its weight behind the state’s narrative of the events.

After international media picked up the Kashmir story, with both the UN chief and Pakistan’s Nawaz Sharif condemning Indian actions and calling for a plebiscite in the disputed region, Indian media has gone into a jingoistic frenzy.

Some top Indian editors not only wished Burhan’s body had been burned “with garbage,” they hailed their soldiers for eliminating the “pig” — thus slaying the same journalistic ethics they tend to teach in journalism schools their organisations run across India.

Others simply started blaming Pakistan for the events unfolding in Kashmir, despite the fact that Pakistan is too much involved in solving its own problems. Since 2008, the non-violent resistance in Kashmir has shown no trace of Pakistan’s involvement. The Indian media, under an unwritten doctrine, often questions the indigenous character of Kashmir’s uprising, which is why local Kashmiris take to social media to counter that narrative.

Indian media seems adamant to repeat the blunders made earlier during its coverage of disasters in Kashmir or Nepal.

With ongoing civil unrest unlikely to end anytime soon, India will likely repeat the mistakes it has committed in the past. It will send more troops and ammunition once the previous bank is exhausted. A group of lawmakers will visit Kashmir, drink coffee in the lawns of some Mughal garden, and promise a time-bound probe into the massive civilian causalities. It will be the repetition of old probes that have so far yielded nothing. As rights activists in the region rightly argue, since 2002 India has ordered more than 170 probes but none of them have resulted in prosecution of the accused.

Sadly Kashmir will keep erupting. Now deceased, Burhan may be more successful in recruiting more boys to join the rebel groups than when he was alive.

It’s high time that India and Pakistan quickly announce a date to start negotiations on the Kashmir dispute, which has been awaiting a solution for almost seven decades now, according to the aspirations of the principal party: Kashmiris, the majority of whom want complete independence or a merger of the territory with neighboring Pakistan, which already administers portion of the divided region since 1947.

Baba Umar is a Kashmiri journalist. He can be reached @Babaumarr.