Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen’s historic apology to the island’s indigenous people on August 1 was a hugely important event, not just for Taiwan, but for Chinese and global modernity. It recognized, and started to deal with, one of the most sensitive and contentious issues amongst the community of those that classify themselves as Han Chinese (93 percent of the population in the People’s Republic and over 97 percent for Taiwan): the often highly unequal, and frequently fraught relations between ethnic communities in their respective territories.

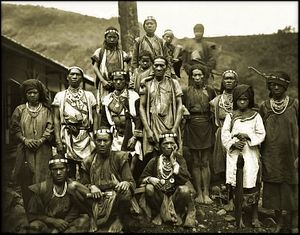

Taiwan’s indigenous people, of which there are 16 officially recognized groups, have an extraordinary history, with some coming from the same groups as New Zealand’s Maoris, enjoying a culture and heritage stretching back tens of thousands of years. Their treatment at the hands of settlers from across the Taiwan Strait in the last four centuries has often been cruel and unjust, with a particularly vicious campaign of repression after Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist armies settled en masse on Taiwan when the Civil War in the Mainland was being lost in 1948-1949.

Chiang, during his quarter century rule over the island, proved no better than his nemesis Mao Zedong in moving from nice sounding language lauding “ethnic minority harmony and equality” to real action to address inequalities. Those classed as minorities often suffered discriminatory treatment. Their economic and health conditions were often inferior to the Han. Residues of this legacy continue to this day, with wealth levels, life expectancy, and representation of the island’s indigenous people in public life all far lower than for the Han.

Tsai’s move is partly a recognition of her own heritage – her grandmother was from the Paiwan tribe. It also sends a powerful message that Taiwanese democratic politics is now able to start dealing with some of the most painful and contentious issues from the past. This stands in stark contrast to the situation on the mainland, where the discourse in this area is still decades behind, with those wishing to raise ethnicity and its political ramifications greeted with harsh reprisals. Uyghur leader Ilham Tohti is the best known of many who have attempted to speak about fairer treatment for ethnic minorities, only to be silenced by draconian prison sentences, with the punishment even extending to their families.

This issue is a huge one. Han Chinese treatment of smaller ethnic communities in modern Chinese history has been one of the darkest and most taboo issues. Mongolians in the Inner Mongolian region during the Cultural Revolution, starting in 1966, endured terrible treatment, with official figures released a decade later admitting that over 20,000 had died. Chinese Muslims were forced to eat pork, and Tibetan monasteries were closed down, with many destroyed. Up to today, similar patterns of exclusion and poverty exist in China’s 55 recognized ethnic minority groups. Attempts to hold the government to account on these issues run the risk of being painted as politically motivated, separatist attacks. The idea of Beijing issuing an apology along the lines that Tsai has for its ethnic communities and the treatment they have received in the last decades, let alone centuries, is currently unimaginable.

Tsai’s apology will no doubt not be widely reported across the Strait. But it does stand as a major historic movement with relevance for all Chinese, not just those in Taiwan. It shows how a Han Chinese-dominated community can start to look at its behavior and record in relations between ethnic groups over the decades and admit to some hard truths. In this, Tsai has possibly been inspired by the actions of leaders like Kevin Rudd in Australia. Rudd’s groundbreaking decision when elected prime minister in 2008 to issue a formal apology to the country’s aborigines was a courageous act, and ranks as perhaps his most important achievement in power.

Tsai’s move is similarly groundbreaking, but it belongs to a particular narrative. Taiwanese have continued to be at the forefront of Chinese modernity for most of the last four decades. The lifting of martial law in the 1980s allowed for the freeing up of civic space, and incremental acceptance of political pluralism. This culminated in the first ever universal franchise, multi-party, free elections in 1996, and the first ever peaceful transition of power from one party to another in 2000. The 2016 apology sets down another marker in this history.

For all its momentousness, however, Tsai will need to reflect on the progress of countries like Australia and the United States as they have come to terms with their past in dealing with ethnic relations issues. America’s election of its first black president, Barack Obama, has not settled huge tensions between ethnic groups in the United States, with the spate of protests, shootings, and attacks with a racial element increasing in the last few years. In Australia, Rudd’s successors have had to deal with Aboriginal communities who still suffer exclusion, with the latest example — the evidence of appalling abuse of prisoners in the Northern Territory — only surfacing last month.

Going along the road to repair and strengthen relations between ethnic groups in any society is an important moment. Plentiful evidence from elsewhere shows it is a tough, and often exhausting journey to take. But at least Tsai’s Taiwan has shown the courage and conviction to start this journey, and for that, they should be applauded and supported.